The Reserve Bank of India, last week, left the policy repo rate unchanged at 5.25 per cent and retained a neutral stance, thereby extending a pause that markets had largely priced in. Now, on the surface, this decision looks puzzling. In a textbook world, when headline inflation softens sharply—well below the RBI’s medium-term target of 4 per cent— and growth remains quite resilient, this signals the moment when central banks cut rates.

However, the RBI chose not to.

The explanation does not lie in ignoring economic theory; rather, it lies in recognising its limits, especially for an economy navigating fragile disinflation at home and a fractured trade order abroad.

Theory vs practice

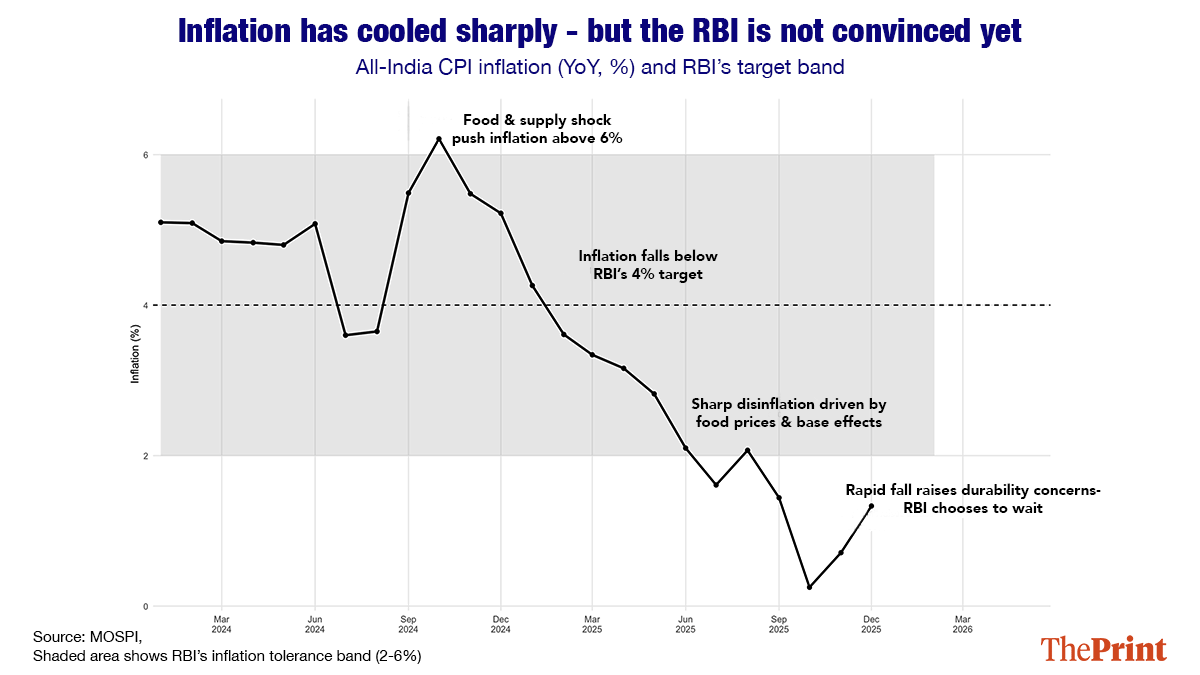

Inflation has undoubtedly eased. The Reserve Bank’s own projections now place Consumer Price Index inflation for FY26 at around 2-2.5 per cent, way below the upper tolerance band and comfortably under the 4 per cent target. Recent inflation readings have been driven down by falling food prices, favourable base effects, and easing supply pressures. This creates ample “policy space” on paper.

However, central banks rarely respond to inflation in isolation; they always respond to the source and durability of inflation. Much of the recent disinflation witnessed has primarily been supply-led and episodic rather than the result of a continued weakening in demand. To be specific, food inflation has a long history of reversing quite quickly in the Indian economy. Hence, cutting rates aggressively on the back of such volatility potentially risks overstimulating demand the minute price pressures return.

And this is exactly where headline inflation can be misleading. As I argued in an earlier column for The Print, low inflation can coexist along with underlying economic weakness and hidden price risks. Treating disinflation as an unqualified green signal for easing can therefore be a policy error, not a virtue.

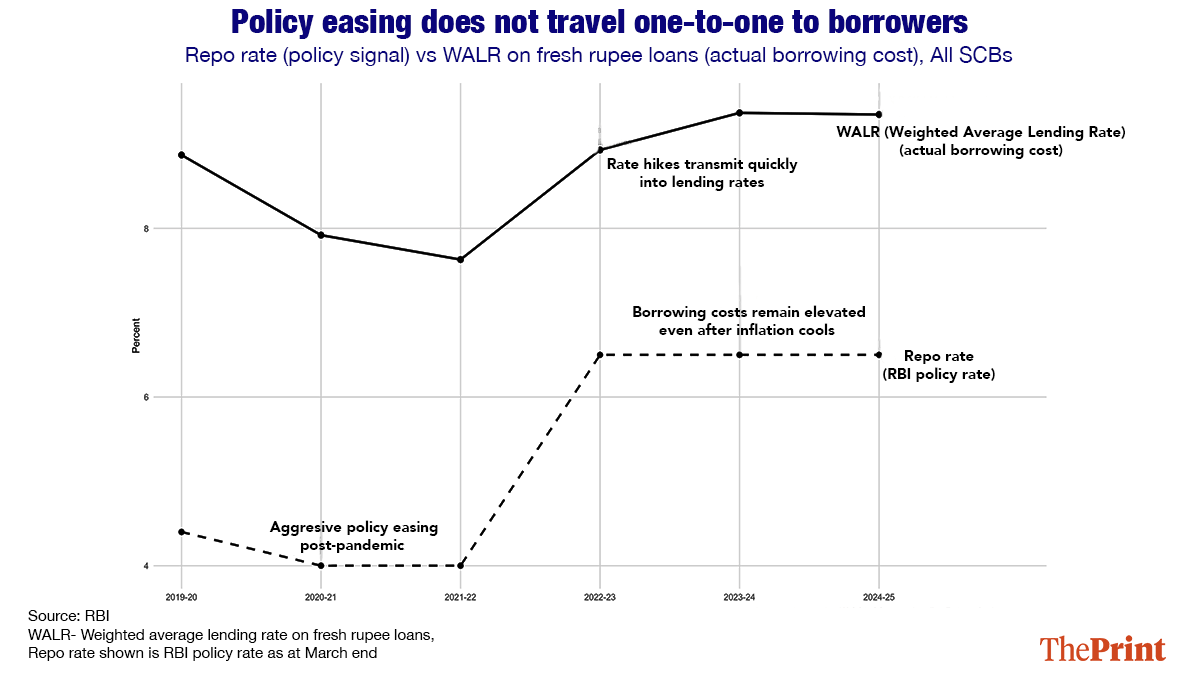

There also lies an important question regarding monetary transmission. The RBI has already delivered substantial monetary easing over the past year, reducing the repo rate from its peak to the current 5.25 per cent. It’s important to understand that these reductions operate with lags. Whether it is bank lending rates, corporate borrowing costs, or household EMIs, they all adjust gradually. Cutting rates again before assessing whether the previous easing has meaningfully lowered financial conditions risks diminishing returns.

The divergence between the repo rate and banks’ lending rates shown in the chart above highlights the asymmetric nature of monetary transmission in India—interest rate changes do not reach borrowers evenly in India. When the RBI tightened monetary policy after 2022 by raising interest rates, banks quickly passed these hikes on to customers. However, when the RBI cut rates post that period, borrowing costs declined slowly and by much less. As a result, even though inflation is easing now, loan rates continue to remain high, thereby limiting the boost to growth from easier policy. This uneven transmission explains the RBI’s caution: Cutting rates too soon may not help borrowers much, while increasing the risk that inflation returns.

In other words, the constraint at present is not policy intent but policy effectiveness. A pause at this point would allow the RBI to evaluate whether cheaper money is actually flowing into productive sectors, rather than inflating asset prices or remaining idle in the financial system.

Neutrality, in this context, is not merely a precautionary measure; rather, it is a matter of sequencing.

Also read: RBI repo rate cut and that ‘rare Goldilocks period’

No stable backdrop

Domestic conditions alone, however, do not explain RBI’s decision on 6 February. The global environment has become an increasingly important part of the Reserve Bank’s calculus. The world economy is shifting away from a predictable, rules-based trade system toward a more fragmented system shaped by geopolitics, tariffs, and strategic decoupling. Shifts in tariff regimes can disrupt supply chains, increase costs, and even reintroduce inflationary pressures that might be difficult to forecast. For India, this matters greatly because tariffs act as supply-side shocks: They raise input costs without boosting demand.

Aggressively reducing interest rates in response to low domestic inflation, while ignoring external cost risks, may leave policymakers exposed when imported pressures resurface. Inflation may look benign today, but global price dynamics can turn quickly. In this environment, policy flexibility carries a premium. By maintaining a neutral stance, the RBI preserves the option to respond if trade disruptions spill over into domestic inflation or capital flows. Premature easing would reduce that room for manoeuvre.

There is also a signalling element: A neutral stance signals to markets that the RBI is not reacting mechanically to short-term data but is weighing risks over time. It signals confidence that the economy does not need constant monetary support, while avoiding a premature declaration that inflation risks are behind us. This departs from the clean logic of textbook monetary policy, which assumes stable trade regimes and predictable inflation. Today’s economy, unfortunately, offers neither. Supply chains are shifting, trade policies remain uncertain, and geopolitical shocks increasingly shape prices. In such a world, practising restraint may be the most stabilising choice for now.

By holding the repo rate at 5.25 per cent and staying neutral, the Reserve Bank of India is effectively buying time—time for past policy moves to work, for inflation trends to prove to be durable, and for the global picture to become clearer. In uncertain times, knowing when not to move can be as important as knowing when to act.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)