Two weeks ago in Delhi, two mothers acted very differently toward their minor sons. Both the boys were involved in sexual crimes, separated only by heinousness. The first mother told the adult victim that she was “overreacting”, while the other handed her 10-year-old son over to the police after learning that he had assaulted a six-year-old child.

Painful details have emerged from the 18 January incident in the Bhajanpura area of northeast Delhi. A six-year-old girl was gang-raped by three minor boys aged 10, 13, and 16, all of whom were friends with the child’s deceased brother. They allegedly lured her to an abandoned terrace, promising her chowmein, and then gagged and restrained her.

The child was found semi-conscious and bleeding heavily, unable to walk. When the mother of the 10-year-old saw the victim’s condition and realised what her son had participated in, she reportedly took him to the police herself.

The other incident happened on the Delhi Metro. A 14/15-year-old boy approached an American woman and requested to take a photo with her. When she agreed, the boy put his arm around her—and then proceeded to grab her breasts and spank her bottom, giggling away. When the woman pushed him away, the boy’s mother sprang to his defence and told her that she was “overreacting”.

The boy had never met a blonde woman up close, the mother explained, and had simply gotten “carried away”. In a message to her Indian professor, the woman has vowed never to return to India.

A few days after the Delhi Metro incident, a woman finishing her morning jog in Bengaluru’s Avalahalli Forest encountered a group of boys aged between 10 and 13 on the trail. They laughed as they passed her and made obscene comments about her clothing and her body. She initially ignored them, attributing it to immaturity, but the comments were explicit enough for her to confront them.

“Where are these kids learning this from? How do they feel entitled to comment on a woman’s body?” she wondered. Last year, a sobbing Bengaluru influencer was groped by a 10-year-old while recording a video.

Delhi tops list in juvenile crimes

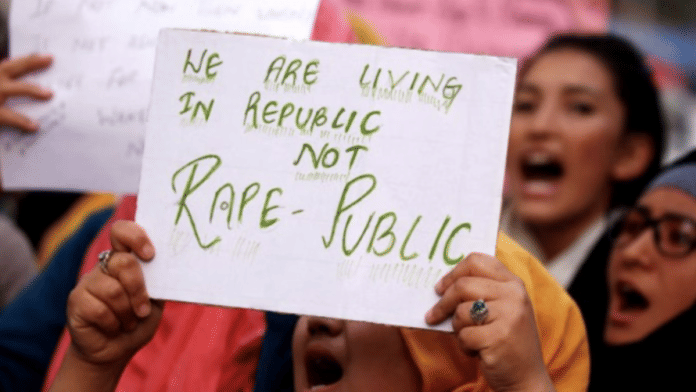

Women in India have long accepted—however bitterly—that navigating public spaces means a constant calculus of threat and risk-assessment. What to wear, which route to take, what time is it, where to sit to avoid being touched by strangers, how to hold your keys or your safety pin sandwiched between your fingers to exert damage at a moment’s notice. We’ve made our exhausted peace with being wary of adult men all the time.

But 10-year-olds? Are we now supposed to add children to the list of people we need to protect ourselves from? Young boys who should be sweating about schoolwork are instead learning how to corner women.

The needle skips to the same groove every time we are jolted by such an incident. Shock and outrage demand that these children be tried as adults—or at the very least, their parents must be publicly hung at the nearest town square. If they are old enough to assault someone, they are old enough to bear the consequences, we say. We examine each case as if it’s a manufacturing defect in an otherwise functioning system.

But we had this conversation last month. And the month before that. And even before that. We are no longer witnessing something exceptional when we witness child-on-child or child-on-adult sexual attacks, and we can no longer think of only exceptional responses.

The data has been staring us in the face. In 2023, juvenile crime in India rose by 2.7 per cent. Delhi topped this dubious list as well, reporting the highest crime rate among children at 41.1 per lakh child population, far outstripping the national average. The nature of the crimes included rape (977) and assault on women with intent to outrage modesty (811).

Also read: New Delhi prefers to look at Manipur as a horizontal problem, not vertical

It all begins at home

Instead of asking what to do with these boys after they’ve committed violence, we should be asking what turned them into boys who commit violence in the first place.

The answer to that… is everywhere. Let’s start with the homes where 30 per cent of Indian women aged 18-49 experience domestic abuse, where children learn firsthand that violence is how men relate to women. There’s a psychoanalytic concept worth understanding here: Containment. Young children need caregivers who can absorb their infantile rage—the toddler’s kicking, screaming, and lashing out—without retaliating, who can process their aggression and return it in manageable form.

However, when mothers are forced to absorb violence themselves, they have nothing left to contain their child’s fury. In turn, the child mimics the aggression they witness.

Then, there is a direct line between being abused and becoming an abuser. As far back as 1987, a US study of 47 boys aged 4 to 13 who had molested younger children found that 49 per cent had themselves been sexually abused, and 19 per cent physically abused. The majority came from families with histories of sexual, physical, and substance abuse. Trauma spreads outwards horizontally, replicating itself.

And now there’s another staggering accelerant. In the UK, children have become the biggest perpetrators of sexual abuse against other children. In 2024, 52 per cent of alleged offenders were minors, up from about a third in 2012. According to the report compiled by the National Police Chiefs’ Council, “in one case a child of four was referred to police after allegedly using a smartphone to upload an indecent image of a sibling.”

A quarter of the 1,07,000 reports in 2022 involved the making and sharing of indecent images, and the overwhelming majority were boys. The report pointed to access to violent pornography and misogynistic, “manosphere” content via smartphones as the driver of this trend.

None of this should be surprising at this point, but it still knocks the wind out of you. A recent poll by YouGov revealed that 27 per cent of young men in the UK (aged between 18 and 29) held a positive view of Andrew Tate, while 24 per cent agree with his views about women. Another poll from 2023 suggested that “56 per cent of fathers under the age of 35 approve of Andrew Tate”.

For those who don’t know him, Tate is the noxious “King of Toxic Masculinity” and faces several charges of rape and human trafficking. When not in prison or getting beaten in a boxing ring, his egregious views on women are broadcast to millions of impressionable young followers.

Also read: Indian judiciary is letting citizens down. When liberty is in danger, judges are looking away

No reconciliation

The classroom has become a testing ground for this worldview, and teachers, the first line of defence, are watching it play out in real time. A February 2025 study documented that boys sent sexist messages to young female staff members. Male students refused to take instruction from female teachers, making derogatory comments about their appearance. A male pupil “who was open about having accessed Andrew Tate’s material,” the report said, “made unacceptable, sexist comments about a female teacher when she gave him a consequence.”

Over at home, this online hatred complements home-bred “Make in India” misogyny, resulting in a pipeline that produces juvenile rapists.

But understanding does not equal resolution. It won’t make the six-year-old in Bhajanpura whole again. What scale can balance one child’s trauma against another’s stolen childhood? Sadly, a crime committed by a 10-year-old is still a crime—even if it was perpetrated by someone who was failed.

When 10-year-olds plan a gang rape, there’s no reconciling—only reckoning.

Karanjeet Kaur is a journalist, former editor of Arré, and a partner at TWO Design. She tweets @Kaju_Katri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)

Most otts are after profit and demand for vulgar content is huge. Reducing supply will not solve the problem of the demand. We as a society need to criminalize marital rape. Many children face abuse in families or have seen the women in their families get abused. It desensitizes them against sexual abuse.

Vulgar content in Instagram and Facebook, is spoiling children. Banning porn sites is not enough. Soft porn is everywhere.

We also need a ban on social media usage for underage children, like Australia did.

Movie ratings also need yo be strictly enforced.

Thanks for your article. It’s an irony of our society that we worship Shivaling and are so reluctant and ashamed of taking anything about sexual awareness; or even on insisting schools on having a formal sex education class/workshop for our children. I wish a time will come when parents would google about how do developed countries take care of their kids!