ThePrint Dalit History Month

My fascination for Dadasaheb Gaikwad has its roots in the failures of our own land struggle. Like me, he too was called a Communist stooge.

The grammar of the Dalit movement in present-day India is locked in the dilemma of what I call abstract versus concrete politics. While we are busy attacking the abstract politics of ideology, we are getting ourselves kicked everyday by the concrete and the material deficits on the ground.

We must prioritise the struggles for the real, material issues of land and resource rights, instead of getting lost and entangled in the rhetorical cycle of politics. We need to go beyond the politics of ‘Manuvaad-Brahmanvaad Murdabad’ to look at the rights of our working classes, farmers, and our access to land ownership.

This is the intersection of Dalit politics where we find icons like Dadasaheb Gaikwad.

I may be berated for saying so, but I wish he was more – or at least as – popular as Kanshi Ram.

My fascination for Dadasaheb Gaikwad has its roots in the failures of our own land struggle. In the aftermath of the Una incident, our rallying cry was: “Gaay ki poonch tum rakho, hamein hamari zameen do!” (You keep the tail of your cow, give us our rightful land!).

Such has been the grip of the upper-caste, upper-class hegemony on all the organs of the state that land reforms, a programme which is in harmony with the preamble of the Indian Constitution, could never materialise.

The work of Dadasaheb Gaikwad holds up the mirror to our failures. It explains why even today, in 2018, a Dalit activist in Gujarat called Bhanubhai Vankar had to immolate himself over a piece of land.

After quitting journalism in 2008-09, I came back to Gujarat, following the call of my heart. I met a Gandhian land-crusader, Chunnibhai Vaid. Unlike most other Gandhians, he was quite a character. Even at 96, he was willing to trudge the villages of Gujarat for the land-struggle. It was at that time I came to know that Dalits in Gujarat had possession of land, but only on paper. But only Ambedkarite activists here were talking of it, not the regular NGOs in the state.

When I read Anand Teltumbde’s book ‘Dalits: Past, Present and Future’, I learnt that even Babasaheb Ambedkar wasn’t able to do much for landless Dalits in his life, even as he set the theoretical bases for it in his work, ‘States & Minorities’. It was after Ambedkar’s death that Dadasaheb Gaikwad emerged among a consortium of leaders of the Republican Party of India (RPI), and he stood out for me because he raised land as a key issue.

In 1959, the RPI found itself divided into two factions, as separate conferences were held in Nagpur and Aurangabad. On one side was B.C. Kamble, the erudite lawyer and constitutionalist. On the other was Dadasaheb Gaikwad, who held his conference in Aurangabad, setting the precedent for his movement demanding the state ownership and redistribution of lands for cultivation.

On 30 July 1959, Dadasaheb Gaikwad went onto lead a land satyagraha across Maharashtra. Approximately 50,000 volunteers, including women and children, launched a jail-bharo (fill the jails) movement, and thousands of Buddhists and non-Buddhist Dalits, Adivasis, as well as caste-Hindus courted arrest. That satyagraha was supported by Communist party leaders and agricultural labourers – that is what comes close to our own struggles today.

Kamble’s faction had more influence on urban, middle-class Dalits. Allegations were made against Dadasaheb Gaikwad; he was called a Communist stooge. It made people uncomfortable that Dadasaheb Gaikwad was raising material issues, just like I did after Una happened.

Post-Una, I was told by other Ambedkarites that I wasn’t doing ‘enough’ for issues such as Dalit self-respect and the cause of Buddhism. Barbs were traded. To some, I too appeared to be a Communist stooge. The difference between Kamble, the constitutionalist, and Dadasaheb, the ‘man of the streets’, is what shapes my own life’s trajectory. Like Dadasaheb, I believe in people’s movements and the need to take to the streets to assert our rights.

Despite the satyagraha of 1959, many promises remained only on paper. By 1964-65, the RPI decided to take the agitation to the national stage. A renewed movement was launched, demanding the nationalisation of land and collectivised farming, introduction of a national minimum wage, a strengthened reservation system and that benefits be extended to Dalit-Buddhists as well. Over 3,60,000 Dalits were locked up across India’s prisons, from Punjab to UP to Maharashtra, as of 30 January 1965. Even today, this stands unprecedented in history, especially with land struggles.

The government ultimately buckled under pressure to fulfil five key demands. But many viewed leaders like Gaikwad a ‘dhotrya’ (dhoti-clad villager), a man raising class-oriented issues affecting both landless Dalits and non-Dalits.

When we talk of workers of the world uniting, it should not be forgotten that many of these working classes are from scheduled caste origins. Today, while some accuse me of being a Leftist ‘sell-out’, Dadasaheb Gaikwad’s success at bridging the gap to launch a unified, pro-poor land-rights movement serves as a poignant reminder that Ambedkarite ethos and Communist struggles will and can fight hand-in-hand.

(As told to independent journalist & activist Sabah Azaad)

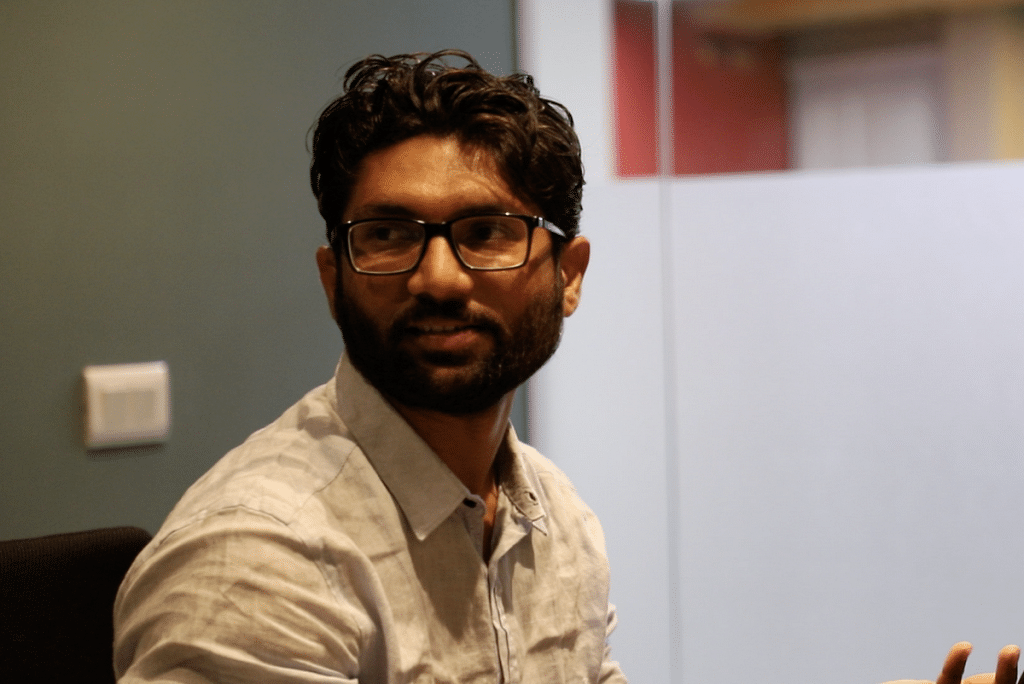

Jignesh Mevani is an independent MLA in the Gujarat assembly and convener of the Rashtriya Dalit Adhikar Manch.

ThePrint is publishing articles on Dalit issues as part of Dalit History Month.

Read more: Dalit history threatens the powerful. That is why they want to erase, destroy and jail it