Earlier this year, the Supreme Court took notice of over 8 lakh execution petitions that are pending before India’s district courts. Under Indian law, the ordeal of a litigant in a civil case does not end with a court judgment. The winner of the case must file a separate petition, known as an execution petition, to enforce the decree or judgment in a civil case. These petitions are filed for recovering money, damages, effectuating suits seeking partitions, the specific performance of contracts, and so on. Even arbitration awards often require the winner of the award to file an execution petition to enforce the award.

In March 2025, the Supreme Court directed all high courts to ensure that district courts dispose of the execution petitions pending before them within six months without fail. Indian courts’ inability to enforce their own decrees within time is a serious, but less studied, problem in India, where most measurement ends at “disposal”. Since execution proceedings necessarily follow a court’s judgment, why do they take so long to dispose of? What explains their large pendency numbers? In a new working paper, we took a deep dive into the data on execution petitions filed in a High Court to answer some of these questions.

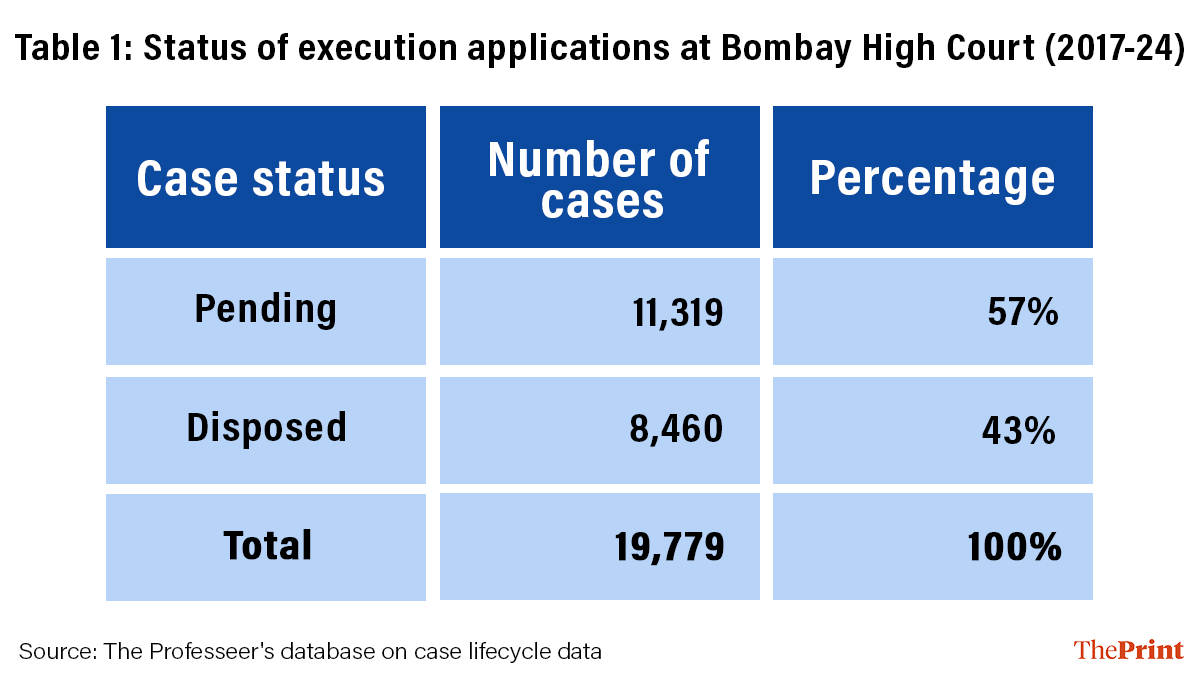

Using data on 19,779 execution petitions filed before the Bombay High Court between 2017 and 2024, we found that execution petitions account for a large proportion of the court’s caseload. On average, they take about two years to get disposed of, and most of them are, in fact, dismissed. We used qualitative interviews to understand these sub-optimal outcomes of execution proceedings.

The day after judgment day

An execution application by the winning litigant (decree holder) is unlike a criminal case. In the latter, as soon as the court’s judgment is pronounced and the sentence drawn up, the State has the prerogative to grab and imprison the convict. In a civil suit, the law assumes that the judgment debtor will either appeal or comply.

If the debtor does not comply, the consequence is not forcing compliance but compelling the decree holder to file a separate proceeding for execution under Chapter XXI of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908.

Apart from the CPC, each executing court has its own execution apparatus. The Bombay High Court, for instance, houses an ‘Execution Department’ under the Office of the Prothonotary and Senior Master and is governed by the Bombay High Court’s Original Side Rules.

Also read: Sheikh Hasina to Tarique Rahman—tradition of political asylum is more than diplomatic courtesy

The aggregates

In our study, we observed that execution petitions account for about 13.84 per cent of the Bombay High Court’s workload. Of the nearly 20,000 cases filed within the period of study, less than half have been disposed of, and over 57% cases remain pending, as of the 31st of December, 2024 [Table 1].

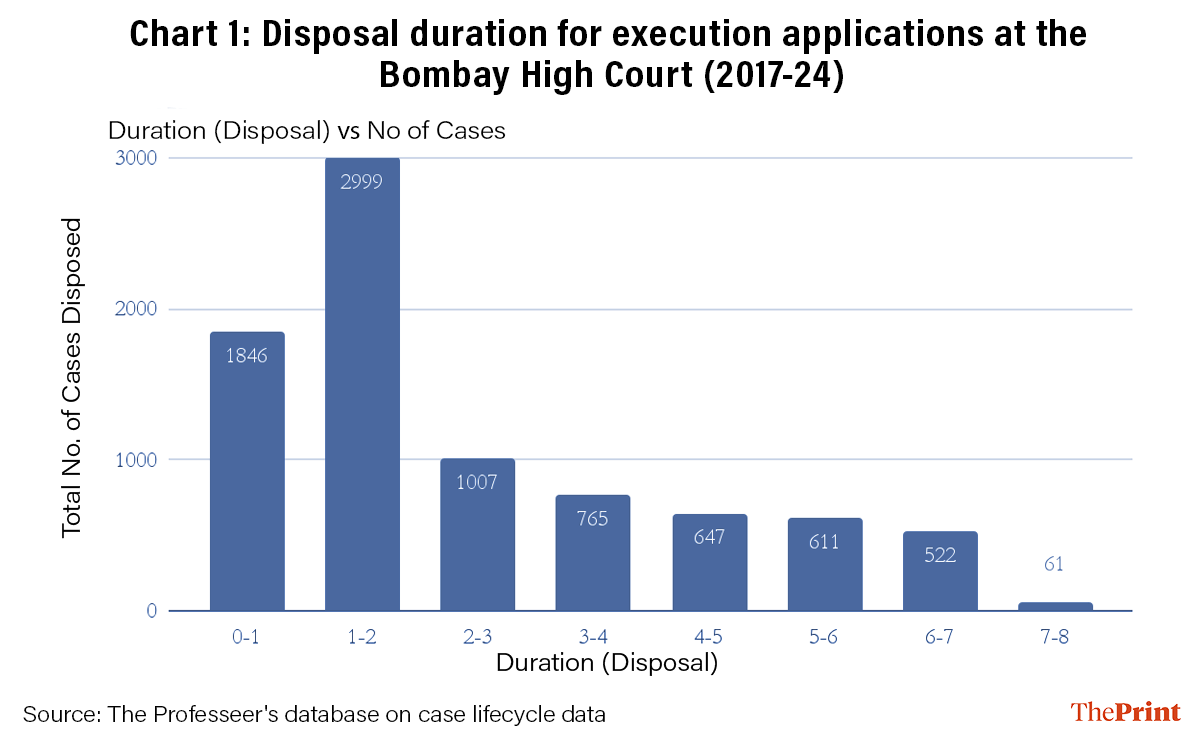

On studying the entire lifecycle of the cases, we find that they take a median of 650 days to disposal—meaning more than half the cases take up to 650 days. Chart 1 below shows that around 70 per cent of these cases are disposed of within the first 3 years of filing. In sum, a predictable cycle of 2-3 years to disposal seems to be the rhythm for a majority of the cases that are disposed of. At the same time, we also found that more than 51 per cent of the pending cases have been languishing in the system for more than two years.

The mismatch is also visible in how, while the median case duration remains 650 days, the average (mean) case duration is 914 days. The substantial difference between the average and median suggests that several execution applications take much longer than 650 days for disposal [see the long tail in Chart 1].

The longest case took 2,857 days (about 8 years). The shortest took just 5 days. To understand what explains this variability and how litigants behave within these execution applications, we studied the nature of these cases and their disposals.

Counterintuitive disposal outcomes

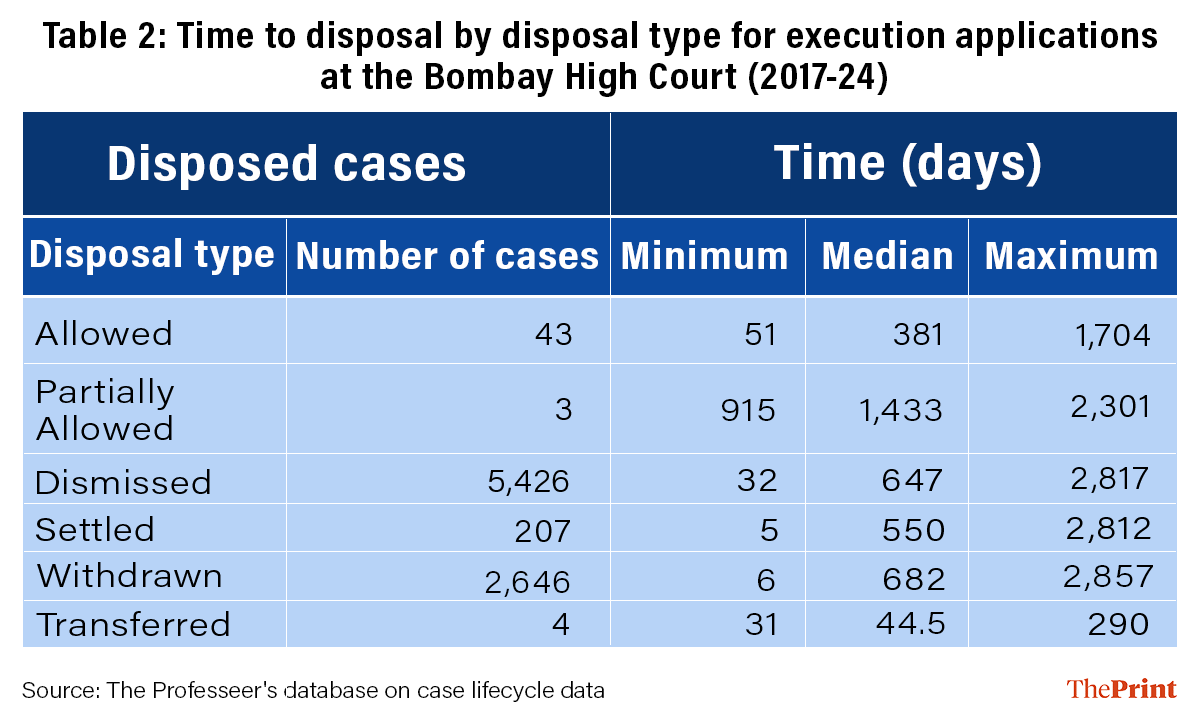

We categorised the 8,460 disposed petitions by the nature of their disposal. If a case is disposed of as “Allowed”, it means the executing court has recognised the original decision on merits and proceeded with execution. Some may be “Dismissed” for improper filings, others “Settled” or “Withdrawn”, and yet others “Transferred” to alternative courts. Since the court’s judgment and decree ought to have settled all questions of fact and law, we assumed that most execution petitions would be allowed without much ado and most decrees would be executed.

The data shows otherwise. We found that only 43 out of these 8,460 applications were allowed. A total of 99 per cent of all disposed cases were either dismissed, settled, or withdrawn (Table 2).

Three insights from Table 2 warrant elaboration.

First, the high dismissal numbers cannot be explained by the court hearing and dismissing execution petitions on merit. In fact, our case lifecycle data shows that most of these dismissed petitions have had not more than one hearing. Most execution petitions are in fact dismissed for non-prosecution—that is, the filing party fails to show up and pursue the execution petition until the end—or for unrectified filing errors.

Second, one-third of these petitions were either settled or withdrawn. What might explain the high proportion of dismissals, settlements, and withdrawals?

An optimistic explanation of these outcomes is that the judgment debtor ends up paying the full amount decreed by the court, so there would be no reason for the decree holder to pursue the execution petition. A less optimistic interpretation would be that the judgment creditor is accepting the amount decreed with a haircut. Given the long pendency period and the fatigue with the long litigation lifecycles, this is a plausible explanation for the disproportionately high dismissals, withdrawals, and settlements.

Third, the relatively high proportion of the execution petitions that get dismissed at the two-year mark (Table 2) suggests that the Execution Department, of its own accord, undertakes a sort of a clean up exercise where unpursued execution petitions are dismissed en masse.

Also read: A slugfest is on in American Right. MAGA is preparing for the post-Trump era

Yet another story of incentives

Our research, motivated by the Supreme Court’s repeated exhortations to deal with the long and large pendency of execution proceedings, makes us question the fundamentals. Does it make sense to keep executions divorced from main proceedings?

The present execution system is a common law vestige that we have mimicked from the United Kingdom. Today, even the UK has a privatised execution industry, competing on timelines and efficiency. A 19th-century system that forces the winner of a litigation to continue running from pillar to post to enforce a hard-won decree, poses an existential question for the judiciary.

But even if we are scared to ask these fundamental questions, we can take solace from the fact that many of these sub-optimal outcomes can be resolved by aligning incentives of the stakeholders involved in execution proceedings.

First, we must incentivise the judges to take decree enforcement cases seriously. Judges are rewarded on aggregate disposals and shorter timelines. For instance, consider a judge who issues a decree in two years, then separately disposes the execution application in another two years. They have double the disposal at half the time when compared with a judge who meticulously links execution to the original decree and scrupulously follows it through for 4-5 years. The system rewards indifference. A 2009 Supreme Court judgment called out this problem, and wondered why the law treats suits and executions as divorced entities. The needle hasn’t moved hence.

Second, lawyers in India cannot charge contingency fees. Having won the case, decree holders’ advocates have little incentive in realising the amount. Our conversation with some practitioners revealed that they hardly ever consider taking up execution applications. A practice in seeing execution petitions through for a client is not glamorous. For the most part, it does not require the lawyer to argue a case on the high principles of law, and so on. Much of it is mundane, preparing a list of assets available for executing the decree, attending auctions, and so on. On the one hand, this reinforces the UK’s adoption of the idea of execution professionals as a separate cadre from practising lawyers. On the other, it questions the idea of a prohibition on success fees for lawyers.

Back to the drawing board

The effectiveness of a legal system cannot be assessed at the point of judgment alone. For an economy aspiring to scale, attract investment, and sustain complex commercial relationships, the credibility of courts depends fundamentally on whether judicial declarations translate into real-world compliance. Our findings suggest that the execution apparatus, in the country’s financial and economic capital, has been hollowed out into a largely symbolic mechanism.

Repeated exhortations from the Supreme Court on expediting the disposal of execution proceedings are an inadequate response to this problem. Instead, it is time to go back to the drawing board and ask fundamental questions on re-designing the law and incentives to mitigate winners’ remorse in Indian civil and commercial litigation.

Pavithra Manivannan is a Research Lead at XKDR Forum. She tweets @PavithraM_.

Gokul Sunoj is an associate at The Professeer. He tweets @GokulSunoj.

Bhargavi Zaveri-Shah is the co-founder and CEO of The Professeer. She tweets @bhargavizaveri.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)