A recent analysis in ThePrint on judicial composition underscored how slow career progression and systemic barriers prevent members of the subordinate judiciary from meaningfully entering the higher courts. A bench led by Justice BR Gavai, which flagged this concern, even floated the idea of quotas for district judges.

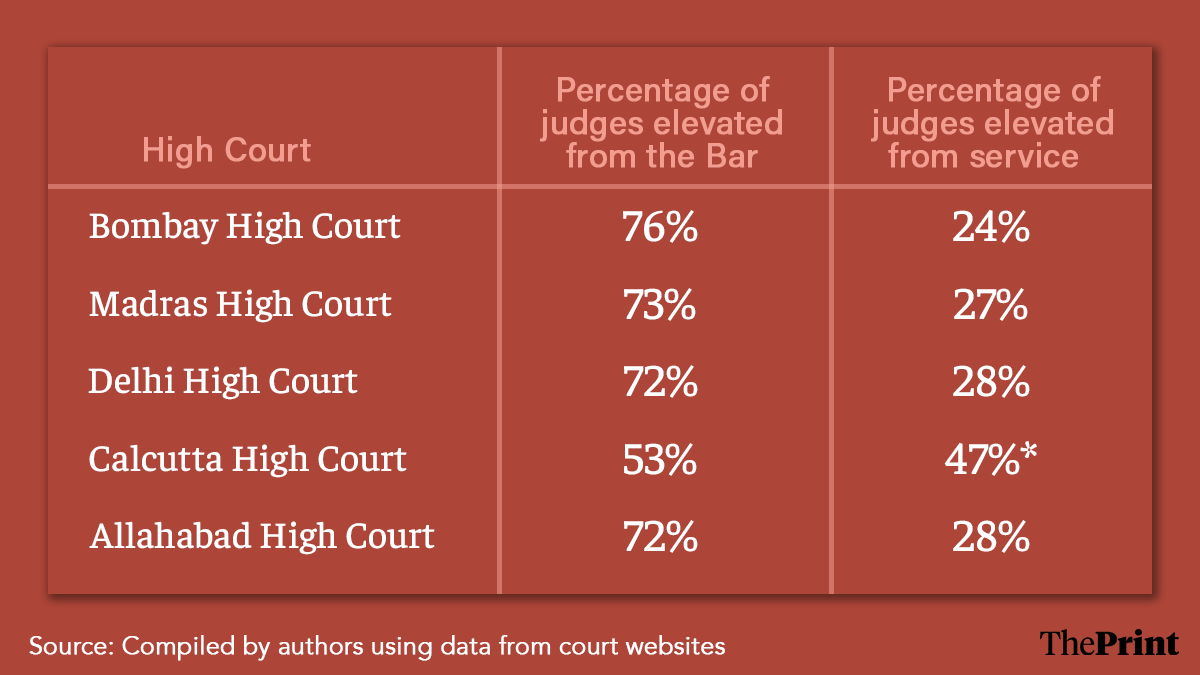

Our analysis of data from major high courts reveals that roughly three quarters of judges are elevated directly from the Bar. The highest percentage composition for service elevated judges is at the High Court of Sikkim. Deceptively at a 50-50 split, the court has just two judges as of 14 December — one of whom has been inducted from service and the other from the Bar. There is not a single case wherein the percentages switch the other way round.

Table 1

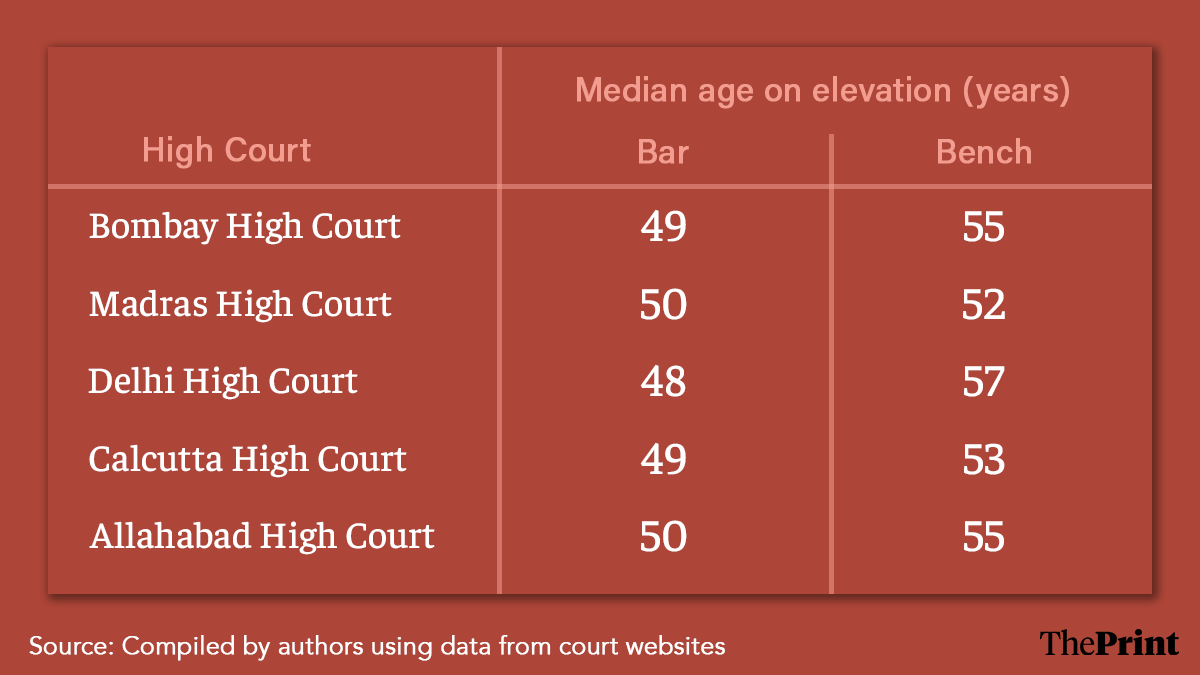

The piece went on to note that judges from the subordinate judiciary were elevated to high courts much later in their careers. We dived into the data to find the claim to be true. As Table 2 shows, judges elevated from service, in most major courts, lag behind their peers from the Bar by about half a decade (Madras being an exception). This has material effects on their seniority thereafter as elaborated below.

Table 2

The inevitable downstream consequence is that rarely does a judge of any high court elevated from judicial services ever stand a chance at appointment to the Supreme Court. Far too few have had this trajectory. The current apex court composition bears witness to this observation. Of the current 33 judges, 31 were first elevated from the Bar to high courts and then to the Supreme Court, and two handpicked directly onto the Supreme Court bench without even serving as high court judges.

But, so what?

This composition might seem benign. It reflects a classical risk-reward trade-off. Those who venture into the space of private practice with greater risks and show immense potential are presented with opportunities of elevation sooner. This divide strikes at the root of the institutional legitimacy of the judicial system for three reasons.

You cannot coach if you haven’t played the game

High court judges oversee the entire district judiciary in their role as ‘administrative judges’. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, 67 judicial districts fall under the administrative supervision of high court judges. Yet nearly 85 per cent of the administrative judges have little experience of the system they oversee.

While some of these members elevated from the Bar have experience practicing in trial courts, it is unrealistic to expect that these judges have had sustained engagement with the district courts that they now oversee. Earlier this year, the Supreme Court advised high courts to consider trial court lawyers for senior designation. It suggested reaching out to district court judges and officers presiding over tribunals to seek recommendations. The same applies to elevations as well. As the situation stands, to gain visibility for elevation, lawyers must have substantial practice in the high court or Supreme Court, not careers rooted in district courts. Those who supervise and exercise inordinate control over the district judiciary today do so without the institutional memory or lived experience that is essential for meaningful reform. Diktats from the upper judiciary demanding “expeditious disposal” or “strict timelines” often ring hollow precisely for this reason.

The imbalance between Bar and bench

A system that rewards star-studded lawyers creates a corrosive imbalance between the Bar and the bench. The symbolic architecture of judicial authority presumes the primacy of a judge within a courtroom. Within its four walls, even the grandest of lawyers bow before the might of the judicial office. In practice, things are far messier. As high court judges are drawn predominantly from the Bar, their professional and social networks remain lawyer-centric. These are the very lawyers who enjoy the greatest visibility, wield disproportionate influence, and frequently appear before those elevated from their own circles.

For members of the subordinate judiciary, this dynamic produces difficult pressures. This is not to say that these judges aren’t independent or steadfast in their commitment to their oath of office. They certainly are. But that — issuing adverse orders against powerful senior lawyers may carry unspoken risks for their career progression, particularly when their own pathways to the high court are already narrow — puts them in a precarious spot.

Mandatory practice requirements widening the gap

This divide is only set to increase with the minimum practice requirements that have recently kicked in. A person is required to practice for three years before attempting the judicial services exam. This has two implications for the composition of the higher courts’ benches. First, it excludes those who can’t afford to practice before district courts. Second, it reduces the chances of district bench members to “make it” to the high court at an earlier age.

Ex-judge Bharat Chugh had raised concerns that such mandates have an exclusionary effect. With guaranteed salaries and largely stable work profiles, judicial services traditionally attracted more first-generation lawyers, students from regional law schools, and candidates who cannot afford the risk profile of private practice. The mandatory practice policy pushes out those who cannot afford the risks of private litigation from the lower judiciary altogether.

Making matters worse, those who do manage to enter judicial services despite these obstacles encounter a near-total glass ceiling when it comes to elevation to the Supreme Court. It offers far too little to the bright and the ambitious. The prestige hierarchy between the two streams becomes even more entrenched. This double exclusion — first at the point of entry and later at the stage of elevation — erodes not just individual aspirations but the social legitimacy of the judicial system itself.

Also read: Nothing suits dictatorship more than a subservient judiciary: Justice HR Khanna

What can be done

It is known that the system is structured through layers of self-selection that consistently privilege those already proximate while filtering out those from underprivileged backgrounds. Solutions like the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) are politically charged and carry their own challenges. Within the existing framework, however, we offer two suggestions:

The first speaks directly to the recurring debate over mandatory practice requirements. Pushing eligibility three years into a litigation landscape notorious for its low or non-existent remuneration does little more than lock out economically disadvantaged graduates. A more creative work-around would be to draw inspiration from the Supreme Court’s recent suggestions on inducting law clerks as district judges.

Once fresh graduates clear the services exams, this period of clerkship can be structured as remunerated, rotational immersion across the breadth of the district judiciary. Two to three years of such exposure would equip entrants with the institutional literacy expected of new judges, without forcing them into precarious litigation work or superficial proof of practice. This model preserves opportunity while strengthening competence.

Second, mandate district court judgeship before elevation to the upper judiciary. Quotas for district judge elevations to the high courts, as former CJI BR Gavai suggested, may work as an immediate numerical fix on percentages, but would still do far too little in addressing the age disparity.

Chief Justices one after the other have spoken highly of our district judiciary. They’ve exclaimed, and rightly so, that the district judiciary forms the backbone of the Indian judicial system. They are in no manner “lower” or “subordinate”. A good way for them to demonstrate the seminal importance of the district judiciary would be to enforce this one to two years of mandatory service in district courts before appointment to high courts — even for direct elevations from the Bar. This will both reduce the age gap on appointment at the high court, as well as ensure that only those who have played in the dirt first-hand are allowed to coach the ones who have to play the game daily.

From a broader perspective, it is important for the collegium to reassess its opaque internal metrics: do they meaningfully recognise the accomplishments of district judges, or do they default toward the star power of capital-city litigators? Can the work of trial court judges ever be evaluated on terms that meaningfully compare with high-visibility practitioners? These are questions that the institution must now confront with sincerity. Only then can the promise of a judiciary grounded in both competence and internal legitimacy be reclaimed.

Gokul Sunoj is an Associate and Siddarth Raman is co-founder and CTO at The Professeer. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)