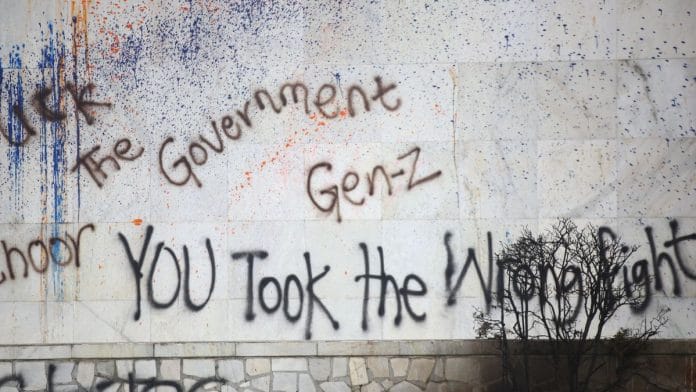

The “Gen Z protests” in Nepal have captured the imagination of young people in China. On social media platforms such as Weibo, Zhihu, Douyin, and Bilibili, Chinese youth are debating the causes behind the unrest.

Many Chinese observers see the demonstrations as fuelled by anger over corruption, nepotism, and economic hardship—but there are more interpretations of it online. For Chinese internet users, the unrest in Kathmandu symbolised suppression of free speech, deepening public distrust, and catalysing mobilisation. They noted how Nepali protesters circumvented restrictions via VPNs and other tools, continuing to organise and amplify their voices until the social media ban was lifted. For some, this highlighted both the power of digital platforms in collective action and the limits of State control.

Not all commentary was sympathetic. Some young scholars and internet users cautioned against romanticising the protests. “It is easy to demolish a house but difficult to build one,” Guo Bingyun, associate researcher at Sichuan International Studies University, observed. He implied that while youth movements may bring down governments, creating sustainable political orders is far more challenging.

A “colour revolution”?

One of the most contested frames among Chinese youth is whether the Nepal protests constitute a “colour revolution.” On Weibo, many posts described the unrest as “ideological colonisation” by the United States and its allies and partners, with direct references to the CIA. “The essence of the Nepalese riots is a military coup in disguise. The people are just disposable tools, and Washington’s purpose has now shifted from building democratic regimes to simply causing trouble,” Shen Yi, assistant dean of the School of International Relations and Public Affairs at Fudan University, argued.

Other posts linked Western-backed NGOs, including those funded by George Soros, to the protests, pointing to familiar colour revolution tactics such as the “clenched fist” symbol and structured campaigns to mobilise Gen Z. This reflects a broader narrative in China that instability in neighbouring, pro-China states is attributed less to domestic grievances than to Western interference.

India also figures prominently in these debates. Posts online argue that New Delhi viewed Nepal’s former Prime Minister KP Oli as too close to Beijing and sought to weaken him. Facing US tariffs on Russian oil imports and the threat of additional duties with the EU, India, it is suggested, needed to curry favour with Washington. Apparently, undermining pro-China politicians in the neighbourhood became one such tactic. From this perspective, Nepal’s unrest and Oli’s resignation served India’s interests by signalling goodwill to the US.

Still, much of the online verdict points to Washington rather than New Delhi as the principal actor. Younger Chinese observers frame Nepal’s turmoil within its fragile geopolitical balance. They argue that if the next leadership tilts West, Nepal risks losing a crucial partner. By contrast, Beijing is consistently portrayed as exercising “patience, confidence, and strategic steadiness” in navigating Kathmandu’s shifting alignments.

A widely shared Weibo post summarised this stance: “Domestic problems do not grant other countries the right to instigate colour revolutions. Each state has the right to pursue its own development path according to its own conditions. Interventions under the banner of ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’ rarely bring progress, but instead generate turmoil and trauma, borne disproportionately by ordinary people.”

For many young Chinese, such interpretations reinforce scepticism toward Western-led democratisation efforts, seen as destabilising. Within this frame, Nepal’s protests appear less as a generational uprising and more as part of a familiar cycle of external manipulation.

Also read: For the Chinese, Modi’s visit opens door—but on China’s terms

Chinese Gen Z in contrast

In Chinese discourse, its Gen Z is portrayed as politically indifferent, yet directing their energies toward digital activism, consumer movements, or effective governance. In contrast, Nepal’s Gen Z took to the streets in large numbers, directly confronting political authority. This juxtaposition not only highlights divergent modes of youth engagement but also shapes how young Chinese interpret political upheaval in neighbouring Nepal. Nepalese youth are seen as testing the power of street politics that turned violent, and Chinese youth are projected as growth-oriented, innovation-driven, politically pragmatic, and largely insulated from Western narratives.

Zhao Qingfan Daqi, deputy director of the Foreign Discourse Innovation Research Center of the Institute of Contemporary China and the World of the China Foreign Languages Bureau, characterises the country’s youth as patriotic, culturally confident, socially responsible, and shaped by China’s rapid development and rising global status. Li Shu, dean of the Communication University of China, notes that programmes such as Why the Communist Party of China and Marx is Right deepen their understanding of Marxism’s sinicisation and strengthen their capacity to analyse complex problems.

In this framing, China emerges as a steady and constructive neighbour, offering stability, infrastructure, and credibility. And its youth mirror these qualities: pragmatic, confident, and detached from Western narratives. Seeing Nepal’s unrest mainly as a Western ploy, Chinese Gen Z reflect on their own place in politics and the economy, highlighting how youth in the region are on very different paths.

Sana Hashmi is a fellow at the Taiwan-Asia Exchange Foundation. She tweets @sanahashmi1. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)