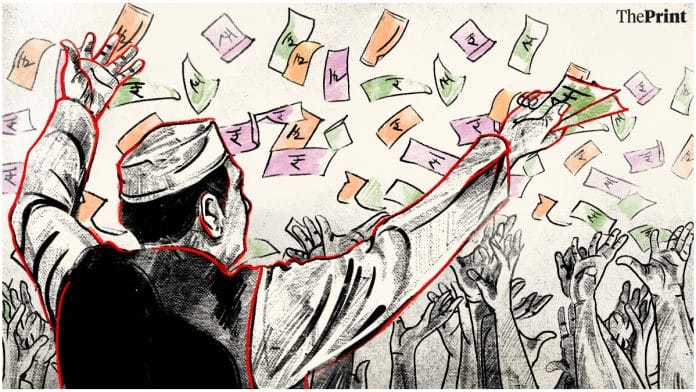

The Bihar Assembly election, which delivered a landslide verdict in favour of the NDA, has reignited the debate on the increasing relevance of welfare promises in Indian electoral politics. It is claimed that the direct cash transfer of Rs 10,000 made to women by the Nitish Kumar-led NDA coalition government just before the polls resulted in increased female voter turnout — a winning recipe for the Bihar election.

This resonates with the prevailing narrative in Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Karnataka, and Telangana, where similar women-centric welfare schemes announced by incumbent governments prior to elections are said to be an enabler in securing success. This narrative dismisses direct cash transfers as a vote-buying tool, robbing these programmes of the chance to become policy innovations. It calls for rethinking.

A shift away from moralism

The negative moralism is built on the premise that cash transfer policies are mere electoral tools to ‘woo’ voters — that these are free giveaways, and thus unwanted. Anthropologist James Ferguson offers perhaps the most compelling challenge to this moral critique and the liberal ideal that treats anything unearned as inherently undeserved. According to him, if the purpose of the welfare state is to secure access to the means of life, then how those means are delivered, whether through employment or direct transfers, should not be the basis for moral judgement. Cash transfers, in his view, are not charity or gifts by the state but “rightful shares” of collective wealth of the society. People deserve material support not because they will become productive workers, but simply because they are members of society with needs and rights.

This perspective shifts the conversation on welfare away from productivity reasoning and toward a deeper moral responsibility of the state toward its citizens. It dissociates welfare from the market logic of cost-effectiveness and justifies welfare as a moral obligation, regardless of any economic returns. This argument challenges the dominant elite narrative that dismisses cash transfers as wasteful or undeserving. It instead creates space for the women, the subalterns — the real stakeholder of these policies — to speak for themselves.

Politics of possibility

Debates around Universal Basic Income (UBI) have gained momentum in recent years. UBI entails a modest, unconditional, and regular cash payment to every citizen as social dividend, ensuring that basic needs are taken care of by the government. It might seem outrightly utopian to many, but economists like Guy Standing and Philippe van Parijs argue that such radical reforms, based on “realistic utopian thinking” and scientific analysis, can reduce poverty and inequality.

According to economist Abhijit Banerjee, evidence-based research shows that assured income security makes people work harder, move from wage labour to more fulfilling self-employment, and gain bargaining power, potentially raising wages and working standards.

Amid failing traditional welfare systems, growing income inequality, and technological advancements, a global landscape has emerged where radical ideas like UBI are being conceptualised and tested through pilot projects across countries, including India, as viable alternatives. In this context, dismissing unconditional cash transfer through the parochial logic of ‘unearned assistance is undeserving’ narrows the space for policy innovation and restricts social mobility possibilities.

Also read: India’s social policy stuck in freebie-welfare debate. Let Ujjwala, Mohalla Clinics coexist

Gendering redistribution

Marxist feminist scholars have argued that domestic work of women is not considered as labour and often justified as familial love and care. However, this unpaid domestic labour is essential for the functioning of the capitalist economy. Thus scholars like Silvia Federici and Maxine Molyneux have long argued for financialising domestic labour in a capitalist society, demanding welfare payments to be termed as wages.

As housework is associated with femininity and is naturalised for women, this idea is radical. Thus, when women emerge as the primary beneficiary of a social policy, regardless of the rationale, it should be seen as feminist redistribution, and not reduced to vote-buying. Such policies benefit not only houseworkers but also working-class women in a largely informal, unregulated, exploitative economy.

Although these policies cannot dismantle structural gender inequality, they can at least indirectly acknowledge and reward women’s undervalued work. A policy approach that frames monetary access as “dole politics” not only questions women’s political literacy and agency in decision-making but also stigmatises them as passive beneficiaries rather than active citizens.

Also read: Cash transfers to women a new dimension in electoral politics. It yields better outcomes

Conclusion

Other than normative debates over the desirability of cash transfers, there is evidence-based research to support that cash transfer is an efficient social policy. A growing body of scholarly literature has shown that well-designed cash transfer programmes can reduce inequality, help households escape poverty, lower child labour rates, and improve health and nutrition measures. A 2023 study by the Center for Financial Inclusion (CFI) found that cash transfers delivered directly to women can strengthen their bargaining power within the household and, in some cases, reduce the risk of intimate partner violence.

Thus, the question is not whether cash transfers are ethically acceptable as welfare policy, but how their implementation can be made more just. In the current context, their announcement in the run-up to elections is often seen as dole politics in a legalised form, raising concerns about political intent and fiscal feasibility, and reducing them to populist tools for broad-based electoral gains.

Making cash transfers sustainable, systematic, and institutionally embedded within a broader welfare vision requires an active legislature, involvement of local government bodies, and an accountability-seeking Opposition committed to the constitutional aspiration of social justice. Ultimately, the challenge is not to prevent cash transfers from being vilified, but to transform them into citizen rights and stop treating them as a negotiating tool for political parties.

The author graduated from the University of Cambridge. She tweets @Banani47917554. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)