In India, the word ‘Macaulay’ is mostly used as an abuse. And those who hurl it hardly ever read a page written by Thomas Babington Macaulay, the British historian who remains a safe target for his abusers. A typical Hindu trait: brave on the dead or weak, shy on the living or strong.

Even after 78 years of Independence, routinely blaming a foreigner who has been dead for more than 150 years is shameful. Our desi rulers have managed to achieve everything they wanted, however odd or momentous. Therefore, we Indians alone are responsible for everything that goes on in the country now.

Dr BR Ambedkar had even underlined this fact in his final speech in the Constituent Assembly on 25 November 1949: “By independence, we have lost the excuse of blaming the British for anything going wrong. If hereafter things go wrong, we will have nobody to blame except ourselves.”

Is it not a disgrace, therefore, that our leaders and so-called public intellectuals continue to use his name even after 76 years of that admonition?

Even more disgraceful is to question Macaulay’s intentions and objectives. All accusations, save one, are groundless. Let us examine them.

Also read: Did English language create captive minds? PM’s Macaulay reference is only half-truth

The lies against Macaulay

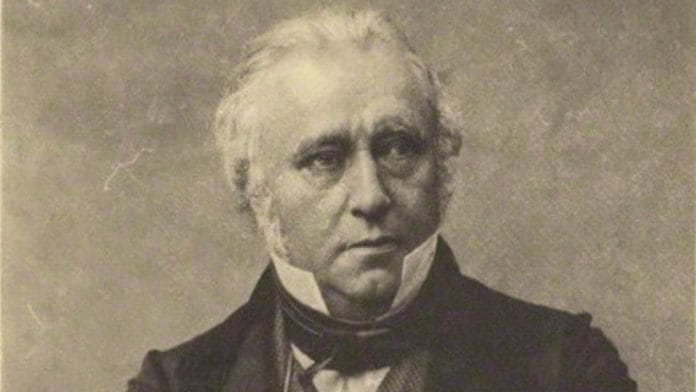

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859) was a British politician, poet, and historian. He first became a Member of Parliament, but when his family’s financial condition worsened, he resigned and decided to work for the East India Company. In 1834, he came to India and was appointed an assistant to Governor-General William Bentinck. He remained in India until 1839. His contributions to the education policy and the Indian Penal Code were significant.

He did advise the government to encourage English learning among Indians, but his reasoning was entirely different from what is propagated today. A whole concocted paragraph has been used for decades to show his ‘evil intent’. The paragraph, propagated as from “Macaulay’s speech in British Parliament on 2 Feb 1935″, has been used even by professors and reputed institutions. It begins thus: “I have travelled across the length and breadth of India and I have not seen one person who is a beggar, who is a thief. Such wealth I have seen in this country, such high moral values, people of such calibre, that I do not think we would ever conquer this country, unless we break the very backbone of this nation…”

The whole text is nothing but a manufactured bundle of lies. Macaulay didn’t deliver any speech in the British Parliament that day because he was in India. He did urge the Committee of Public Education in India to recommend that the East India Company government stop providing any assistance to the traditional Sanskrit and Arabic education in the country. He asked to introduce European literature and knowledge to Indians. But his arguments were the opposite of what is attributed to him.

His ‘Minute on Indian Education’ is a brief ten-page document. In it, Macaulay presented his points in 36 items, which Bentinck accepted. But even that was not imposed on Indians. The government, on its own part, only changed its policy of support — instead of providing support to Arabic and Sanskrit, it decided to promote English publications. Indians were still free to conduct their own education and choose their texts, a practice that continued until the end of the British Raj. Education in any medium at any point was never made compulsory.

In fact, half of the members in that Committee, all Englishmen, supported traditional Indian education in Arabic and Sanskrit. They argued that in order to keep Indians friendly towards the regime, it was better that native language, literature, and education be supported. Macaulay opposed it, not because of any ‘conspiracy’ to ‘destroy Indian culture’, but because he wanted to raise the opportunities for Indians and bring them on par with the Europeans in the job market.

Also read: Not just Nehru, even Hindutva stems from Macaulay legacy

What did Macaulay really do?

Macaulay’s first argument was that by granting aid to traditional education, the British were not helping Indians. After studying in a Sanskrit college for several years and obtaining a certificate, its graduates would turn to the government for a job, because that education would not make them useful for any work in society. Is it any different today? Students still do not find that education beneficial in any form.

Thus, Macaulay’s chief argument was that Sanskrit and Arabic education was futile, even as he acknowledged he did not know either language. Yet, on the basis of some translations and observations from European scholars, he came to believe “that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” A wrong conclusion, yes. But there was neither malice, nor conspiracy. In fact, Macaulay was full of goodwill in recommending European literature.

See his argument: “We found a sanatorium on a spot which we suppose to be healthy…We commence the erection of a pier. Is it a violation of the public faith to stop the works, if we afterwards see reason to believe that the building will be useless?”

Traditional Indian education, Macaulay argued, was similarly pointless. Macaulay argued, howsoever wrongly, that Indian languages were devoid of useful knowledge, and that it was difficult to make Indians educationally relevant unless they learn a foreign language.

Interestingly, Macaulay gave an example from European history. Centuries ago, many Europeans were in a similar condition. His argument: “Had our ancestors acted … had they neglected the language of Thucydides and Plato, and the language of Cicero and Tacitus… would England ever have been what she now is? What the Greek and Latin were to the contemporaries of More and Ascham, our tongue is to the people of India.”

This shows the intent of Macaulay. He was not making it up; he was speaking to the British officials, not Indians. That if the Europeans had remained confined only to the small pamphlets of their native Anglo-Saxon and Norman languages of the time, England would not have become what she did.

Further, Macaulay observed that Indians, too, wanted to study English, instead of Sanskrit and Arabic. According to him, even when the East India Company printed Sanskrit and Arabic books, people neither bought them nor read them even when given free. They lay useless in the stock. English books, on the other hand, were lapped up, and were profitable to the publishers. Thus, the Company government was giving Indians native literature they did not like (how many Hindus today buy Sanskrit books?), while ignoring what they did like.

For Macaulay, it was a fight for a wiser course. His words: “Bounties and premiums, such as ought not to be given even for the propagation of truth, we lavish on false texts and false philosophy. … What we spend on the Arabic and Sanscrit Colleges is not merely a dead loss to the cause of truth. It is bounty-money paid to raise up champions of error.” In the same strain, he lamented: “We are a Board for wasting public money, for printing books which are of less value than the paper on which they are printed … for giving artificial encouragement to absurd history, absurd metaphysics, absurd physics, absurd theology …”

Replying to practical objections, Macaulay said that since the Indian Penal Code was soon going to be created, the existing Hindu and Islamic laws would become defunct. Therefore, the need for knowing Sanskrit and Arabic for that purpose would also end.

Macaulay also observed that Indians did not find it difficult to learn English. Therefore, it was wrong to say that they will remain barely literate in an alien language. According to him: “Indeed it is unusual to find, even in the literary circles of the Continent, any foreigner who can express himself in English with so much facility and correctness as we find in many Hindoos.”

Also read: Why Dalits love Mahatma Macaulay

The ghost of Macaulay still haunts India

Now let’s look at another of his arguments that continues to raise hackles today: “It is impossible for us, with our limited means, to attempt to educate the body of the people. We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.”

As is evident from the argument in its entirety, Macaulay’s intent was quite different from what has been propagated by Indian leaders and public intellectuals. They love to live in their own sectarian mental chambers, where abusing dead foes becomes a comfortable alternative to really learn, think, face realities, and work hard to bring a good change. All education policy documents since Independence, and the real development on the ground, are evidence of how pathetic the desi wisdom in intellectual governance has been all along. There is no correlation between stated goals and ground results.

India’s post-Independence rulers have not been able to change any of Macaulay’s policies in the last eight decades, despite producing dozens of policy documents and writing hundreds of pages. Macaulay still rules over them, because he stated some truths that were impossible to refute. He relied on truth as he perceived it, whereas India’s rulers rely on propaganda they imagine to be efficacious. Macaulay also cared for people. We don’t. Perhaps that made the difference.

Shankar Sharan is a columnist and professor of political science. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)

Typical Hindu trait !! Shame on this writer. shame on the The Print staff

Shocking to see this kind of defence. Sure, propaganda relies on half-truths such as the quote about breaking the backbone of Bharatiya education. But it is hard to deny the overt supremacism in the British policy. You don’t need to ban traditional education outright to impose it – the economic genius lies in making it irrelevant, so there is always the illusion of choice even as the choice makes itself for reasons of pragmatism. That’s my one big complaint with “independent” Bharata as well – Bharatiya language medium education is irrelevant as an option if you eventually (for higher education or a job) must, at some point, switch to English. It is a choice, yes, but a choice no person would like to make rationally. Hence an imposition without imposition.

Also it is disappointing that the article treats Sanskrit and Arabic as equals throughout. The British might’ve opposed both, but let’s not forget that we were colonised by Arabic and Farsi first – a deeper colonisation that has left an indelible mark on many languages down to pronunciation and words that don’t represent our thought but have subtly replaced it.

(Also before anyone points out: Would’ve replied in Hindi or Sanskrit if the original were in that language.)

Achha aadmi thaa. At least I owe a lot to him.

Puke-worthy socialism is the main culprit for India’s failures.