If there are big discoveries to report, relatively little attention will be paid to the preposterous.

The amount of information in a message, American engineer-mathematician Claude Shannon realised, is closely associated with its uncertainty. Shannon’s pioneering work on information theory follows from the simple insight that the more surprising a message is, the more information it carries. If you get a text message saying ‘the sun will set around 6 pm this evening’, you are likely to ignore it. But if the message reads ‘expect heavy snowfall tonight’, you would be jolted into attention.

That’s because it is almost certain that the sun will set in the evening, but the chances of snowfall in India anywhere south of the Himalayas are almost zero.

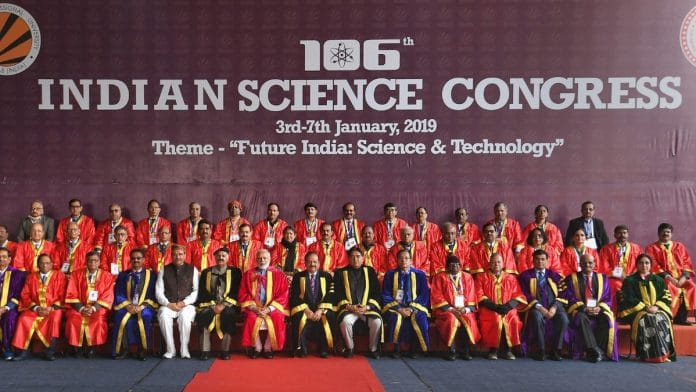

That’s why bad news makes headlines. Conversely, we should start worrying if good news is considered headline-worthy. That’s why most of what was reported about the 106th Indian Science Congress last week was about ancient Indians possessing stem-cell technology and the need to rename gravitational waves as Modi waves. As Roshni Chakrabarty, a journalist covering the Congress, wrote there were ‘hundreds of mind-blowing, groundbreaking lectures’ but what caught public attention were the two making outlandish claims.

Also read: Modi’s space dream: India still doesn’t know the difference between tech & science

Writing about the affair, K. Vijay Raghavan, principal scientific adviser to the government, noted in his blog that ‘a group of scientists, chosen by the ISCA, requests applications to speak and chooses speakers. Once chosen there is no censorship on what the person actually speaks… it’s precisely the diversity and lack of tight organisation that makes it special. Perhaps one should just embrace that. The talks, then reflect the speakers. A few are superb, some good, many unremarkable and few, usually one or two, outright preposterous.’

He has a very good point. Diversity is a good thing. The openness to heterodox ideas is central to science. The question is not one of principle but one of judgment. The scientists and administrators must reflect on whether their decision to admit weird speakers merely for the sake of ‘diversity’ and without imposing the high standards of scientific rigour is worth the overshadowing of the work of hundreds of good scientists. Surely, the meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science can hardly be called lacking in diversity because they don’t allow speakers from the Flat Earth Society.

There’s another reason why there seems to be man-bites-dog kind of reporting around the Indian Science Congress: the absence of massive, genuine scientific breakthroughs.

Also read: Indian Science Congress vows to get its science speakers right after Kauravas & Newton row

I have not studied the proceedings, so I could be wrong here, but if good uncertainties are lacking, the media will report the bad uncertainties. In the absence of startling scientific discoveries, it is much easier for public interest in the conference to be hijacked by a few people making preposterous claims.

We should, therefore, be more concerned about getting more focus, more government investment, more institutions and better communication about science. If there are big discoveries to report, relatively little attention will be paid to the preposterous.

Pure science requires government investment, but we’re not investing enough. India’s spending on R&D has remained stagnant at around 0.7 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP), compared to China’s 2.1 per cent. Not only are we underinvesting in absolute terms, we are underinvesting as a proportion of our national income.

Given the inefficiencies of our governmental system, it’s quite likely that our R&D expenditure has a very poor teeth-to-tail ratio, with much of our science budget being spent on non-scientific activities.

‘Jai anusandhan’ is a nice slogan, but let us remember that both the kisan and the jawan, who have been ‘Jai-ed’ for a long time, suffer from underinvestment. Unless backed by budgets and coherent plans, slogans are counterproductive in the sense that they convey the false impression that something is important and underway.

Those concerned with promoting traditional Indian knowledge should be worried too. Making absurd claims at scientific conferences on the back of political power turns India into a laughing stock. It makes the world’s scientific community a lot more dubious about genuine and promising insights from tradition.

Also read: This Indian scientist says Newton & Einstein are wrong, Harsh Vardhan better than Kalam

What we need is greater investment in scientific research focusing on understanding traditional knowledge systems, and extending it from where it ends. For instance, scientists from Bangalore’s Institute for Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine have found evidence that water kept in copper vessels destroys some bacteria and viruses and can be used as a cost-effective purification method.

The 106th Indian Science Congress was convened at Jalandhar’s Lovely Professional University. It attracted hundreds of scientists from smaller cities and towns, and thousands of students from the vicinity. All this is worth celebrating.

Those on whose shoulders lie the responsibility of stewarding India’s science ought to use Shannon’s insight as they reflect on the past week’s events.

Nitin Pai is director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy.

“Making absurd claims at scientific conferences on the back of political power turns India into a laughing stock. It makes the world’s scientific community a lot more dubious about genuine and promising insights from tradition.” This is the danger with these clowns being offered a platform in what is supposed to be a science conference. Absence of work of great merit is one thing, but ludicrous comedy is another!

I feel it is better not to have an Indian Science Congress at all rather than this farce!