We learn from history that we do not learn inconvenient truths from history. We completed 78 full years of our independence this year, but we have not learned to freely accept towering women and men with their warts and all from our history books who helped shape the idea of India. Instead, we either make holy cows out of complex personalities or exhume them from time to time to fight our many narrative battles.

Then there are those who remain forever confined to the footnotes of history to avoid difficult conversations around ideas they had put forth, which would not stand the test of political correctness of our current times.

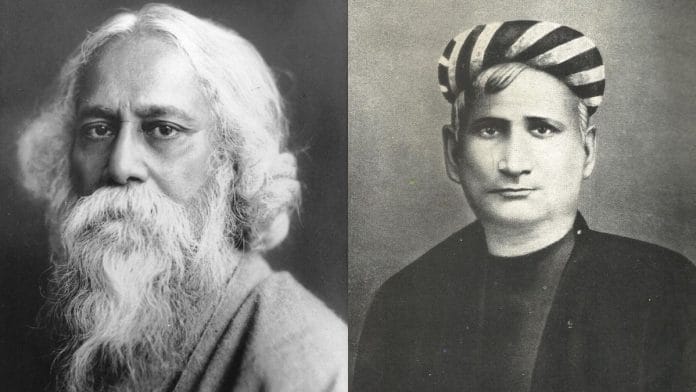

One such figure is that of Sahitya Samrat Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, the author of 14 novels, several satirical, scientific, and critical treatises in Bengali, and the poem Vande Mataram that was adopted as the national song of the Republic of India in 1950.

A heated debate

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the song originally penned in Sanskrit and Bengali. “Vande Mataram” translates to “I bow to thee, Mother”, and it appeared in Chatterjee’s 1882 novel Anandamath. It became the freedom song for armed revolutionaries who invoked and drew strength from the idea of Bharat Mata to fight against colonial rule. But it was this very idea, of reimagining one’s motherland as a mother goddess for the nation and its people, that led to the omission of certain verses of the song in 1937 by the Congress Working Committee (CWC).

A century and a half later, the deletion has ignited a heated debate between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Opposition Congress, with the former asserting that the fragmentation of the song sowed the seeds of India’s partition.

“The spirit of Vande Mataram illuminated the entire nation during the freedom struggle. But unfortunately, in 1937, crucial verses of Vande Mataram, a part of its soul, were severed. Vande Mataram was broken; it was torn into pieces. This division of Vande Mataram also sowed the seeds of division of the country. This great mantra of nation building—why was this injustice done to it?” Modi said on 7 November at an event to celebrate 150 years of the national song. The Prime Minister said today’s generation must understand this history because that “same divisive thinking remains a challenge for the country even today”.

The Congress was quick to hit back, with Congress General Secretary (Communications) Jairam Ramesh saying the Prime Minister had “insulted” both the CWC and Rabindranath Tagore, whose advice had shaped the decision to retain only the first two stanzas of the national song for official use.

Giving an account of the CWC that met in Kolkata between October 26 and 1 November 1937, Ramesh, in a post on X, said those present included Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, Rajendra Prasad, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Sarojini Naidu, JB Kripalani, Bhulabhai Desai, Jamnalal Bajaj, Narendra Deva, and others.

While the BJP and the Congress fighting over national icons from the past is nothing new, with the two parties having sparred over the likes of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Vallabhbhai Patel before, the current controversy brought to the fore a troubling question: Why doesn’t modern Bengal celebrate the Sahitya Samrat in the way it reveres Tagore and other literary and cultural heroes?

Also read: Modi thinks he can win Bengal just like Bihar. Five reasons why he’s wrong

Bankim left out

Political scientist Ayan Guha, a British Academy International Fellow at the University of Sussex, blames Bengal’s othering of Bankim to the hangover of Leftist political culture. “The decline of the Leftist political parties should not be simplistically seen as the decline of left ideology in West Bengal. During the long rule of the Left Front, the Left was able to fashion a political common sense which shapes the way Bengalis understand politics. The slogan Ma, Mati, Manush by Mamata Banerjee is a product of that Leftist common sense,” Guha told me.

According to him, you don’t need to be Left to be Left in Bengal. “It is a unique Bengali political paradox,” he said, “You may be deeply critical of the political Left while embracing the Left culturally.”

And it is this “Leftist common sense” that had kept the Sahitya Samrat out of popular consciousness due to his assertion of the Hindu religious identity. And made Tagore a far more acceptable icon for the modern Bengali.

At the launch of a new edition of Four Chapters, an English translation of Tagore’s 1934 book Char Adhyay, in Kolkata last year, Himadri Lahiri, former professor of English and Cultural Studies at The University of Burdwan, had argued that Tagore’s idea of nationalism was not static, unlike the likes of Bankim Chatterjee.

What he thought about nationalism in the 1890s, he moved away from it by the time he wrote Char Adhyay, Lahiri had said. “Three novels by Tagore — Gora (1909), Ghare Baire or The Home and the World (1916), and Char Adhyay — show his gradual shift away from aggressive or revolutionary nationalism,” he said.

According to Lahiri, Tagore was not just critiquing the idea of nationalism promoted by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s work. He was also questioning his earlier self, which leaned significantly toward the Swadeshi movement. Lahiri believed that Tagore’s fear of what aggressive nationalism could lead to is seen today in the normalisation of a certain kind of political rhetoric, and the rise of world leaders such as Narendra Modi and Donald Trump.

Subhrajit Mitra, director of the Bengali film Devi Chowdhurani based on Chatterjee’s novel of the same name that released in September to commercial and critical acclaim, told me it is the Sahitya Samrat’s religiosity that makes today’s Bengali filmmakers sceptical about Chatterjee.

“We are stuck with (Satyajit) Ray, (Mrinal) Sen, and (Ritwik) Ghatak. They were legends, no doubt, but should we not make films on our armed revolutionaries also? India has almost forgotten the names of most Bengali women and men who took up arms against the British and made the supreme sacrifice. Stories of Anushilon Samiti (fitness club that protected a secret society of anti-British armed revolutionaries) could be the subject of so many films,” Mitra had told me before his film’s release. “But they aren’t,” he had rued.

But this “Leftist common sense” is now under serious challenge due to the increasing use of religious idioms in political mobilisation in West Bengal. But the sense has penetrated so deep in Bengali political consciousness that electoral mobilisation by the likes of the BJP may not be enough. What Bengal needs desperately is to embrace its glorious past, exhume its heroes with warts and all, and not shy away from heated debates. On the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram, we owe ourselves this much.

Deep Halder is an author and a contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets @deepscribble. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)