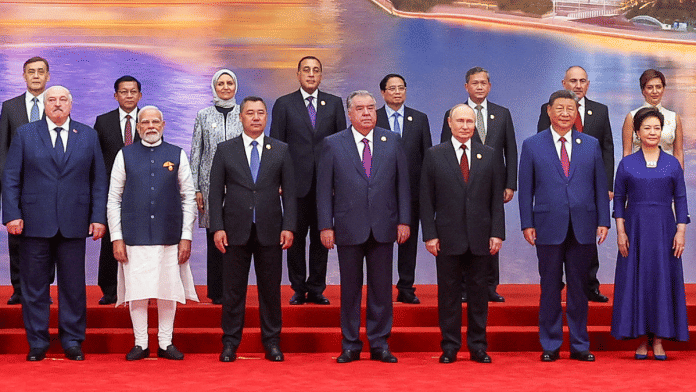

The Shanghai Security Cooperation in Tianjin is not just a standalone annual regional summit. Beijing is actually trying to capitalise on every missing piece in the international global order. President Xi Jinping hosted leaders of the SCO—a Eurasian alliance focused on political, economic, and security cooperation, founded in 2001, which has been a key gathering of members like China, Russia, and India, making it a key regional bloc.

Xi held bilateral dialogues with almost all visiting dignitaries, including observer members. But the key highlight was the Xi-Modi meet-up, where the two leaders continued from their last conversation on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia, in October 2024. This was not only Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first visit to China in the last seven years, but also the most substantial one since the two sides signed the agreement on military disengagement and maintaining peace and tranquillity at the Line of Actual Control (LAC) last October. The India-China Summit on the sidelines of the SCO was certainly a requirement following the resumption of diplomatic engagements.

Meanwhile, amid the looming tensions between US President Donald Trump and the rest, the global media perspective is that the key powers will align. This was true in some senses, as China and India—the two key Asian economies—reaffirmed that the “two countries were development partners and not rivals, and that their differences should not turn into disputes.” Looking at the dependencies that India and China have on each other, mainly driven by business and trade, and given the cost of conflict, the two coming to terms and re-negotiating their neighbourly co-existence may be good news.

Expecting anything more from India and China ties would require cautious optimism from New Delhi, even though some China watchers argue that India may seek deeper ties with China amid growing tensions with the United States. But the two relationships have varying trade volumes and strategic interests.

Loyalties matter to China

Besides a regional summit and a Modi-Xi meeting, a third event will keep Beijing busy—Victory Day, marking the 80th anniversary of China’s victory against Japan and the broader victory of the Allied forces against the fascist forces in World War II. The presence of 26 foreign leaders, including Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un, in Beijing will show China’s growing popularity in the non-Western world. While the historical relevance of the parade adheres to embarrassing Japan over its colonial past, this time, Beijing is pitching the occasion to project power—staging its largest-ever Victory Day military parade to flaunt the scale of its modernisation and the sophistication of its latest military advancements.

There remains little doubt over China’s proven military prowess—if not a match for the Americans, it indeed is a wakeup call to many neighbouring countries, especially India, which remains on high alert at the LAC.

Far from bilateral equations and global aspirations, China is also seeking an alignment of ideologies and making itself central in India’s neighbourhood.

Strategising centrality in the Indian subcontinent

Among many world leaders, the Prime Minister of Nepal, KP Sharma Oli, the Maldivian President, Mohamed Muizzu, and the Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif—leaders from India’s neighbouring countries whom Beijing has been luring through strategic partnerships—will attend the Victory Day celebrations. Interestingly, all three countries have also enjoyed a deep development partnership and people-to-people ties with Japan, and hence, questions are raised whether it is their right diplomatic stance to attend the event.

Even though the Pakistani and Maldivian media remain calm about questioning their leaders’ attendance at an anti-Japan event in China, the Nepalese seem baffled over Oli’s participation. They are questioning the diplomatic call for Kathmandu to stand against a friendly nation that hosts a significant Nepalese diaspora. This raises a billion-dollar question: Does such participation align with Nepal’s constitutionally projected non-aligned foreign policy stance?

India is concerned by China’s growing lead in the subregional setting. In past months, China has hosted leaders from South Asian countries in minilateral settings—hosting the first-ever China-Bangladesh-Pakistan trilateral summit in Kunming in June, followed weeks later by a tripartite with Afghanistan and Pakistan. With the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) still defunct, such a China-led minilateral may be the most consequential development in recent years.

What stands out in Beijing’s minilateral with countries of the Indian subcontinent is not potential cooperation but the odds they represent—Afghanistan and Pakistan share a contested border, and Bangladesh’s 1971 independence left it a rival of Pakistan. Yet China has succeeded not only in bringing them together but also in positioning itself as the indispensable convener. This is no accident, but part of Beijing’s overall strategy concerning the Indian subcontinent, positioning itself as the centre of gravity, aided by shifts in India’s equations with neighbouring countries.

At the same time, China is offering infrastructure deals, trade access and diplomatic cover to India’s neighbours, coaxing them into endorsing its ‘national unification’ narratives, most notably over Taiwan. In fact, joint statements now explicitly mention Taiwan. Lines such as “China’s the sole legal government representing the people of China, and Taiwan is an inalienable part of China’s territory” are an added explanation to what was previously put as a vague endorsement of the “One China” principle.

Therefore, Beijing is undoubtedly building not just influence, but an architecture of dependencies that either carries an anti-India projection or forces these countries into a posture of strategic silence when India’s interests are at stake. It reflects changing regional alliances and leadership. From where we are placed today, accepting Chinese influence will be a step forward in building counters and solutions.

To conclude, Beijing’s dual strategy helps it balance relations—offering rhetorical warmth to India when convenient for business and trade, while strongly opposing a Trump-led global order. Simultaneously, it is quietly expanding its influence in India’s immediate periphery, with outcomes like Nepal supporting China’s stance on Taiwan or joining its coordinated commemorations. Such gestures may not signal real agreement, but they bolster China’s centralising efforts in the region.

Rishi Gupta is a commentator on global affairs. Views are personal.