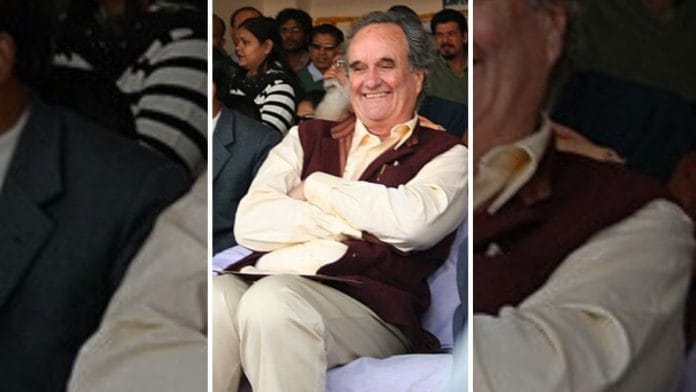

For 20 years of the crucial history of the last century, Mark Tully was famously known as the ‘Voice of India’.

What is not often said is that he was the voice of India for Indians. As the BBC World Service Radio’s man in New Delhi from the 1970s into the 1990s, Tully told us what was happening in our country and the neighbourhood when All India Radio (AIR) and Doordarshan’s news bulletins only gave us the government version of events.

At critical junctures in those tumultuous years, ‘Tully sahib’ presented it like it was.

Be it the Bangladesh War in 1971, the 1975 Emergency before then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared him persona non grata, Operation Bluestar in June 1984 and Indira Gandhi’s assassination on 31 October 1984, we learnt about them from Tully on BBC World Service.

He reported for more than 20 years on events in India and the subcontinent from the 1970s to the 1990s. And we listened to him. Millions huddled around the radio set or transistor radios for the BBC World Service news bulletin at least once in the morning and once in the evening—just to learn what was happening in the world, and our world.

Although he reported on news and developments in India ranging from politics to agriculture, education to elections, Tully will be most remembered as the messenger of bad news. When things went wrong, when the going got tough, Tully got onto the radio and told us about it, in a grim, sombre voice.

What’s critical here is that we did not believe the news until ‘Tully sahib’ had confirmed it. Rumours abounded on the morning of Indira Gandhi’s death, but we waited until Mark Tully had announced it on the air before we accepted it.

While AIR and Doordarshan droned on with mournful music, Tully described Mrs Gandhi’s killing by her own security guards. Thereafter, we would clock in for each hourly news bulletin on the BBC World Service, waiting to hear the latest on the Delhi riots. Those of us in Delhi saw the plumes of smoke from fires and heard the drums of death, but we waited for Tully to tell us what was happening.

Also read:Mark Tully’s BBC assignment to India wasn’t by chance. It was a karmic connection

Bhopal gas tragedy to Rajiv Gandhi assassination

It was the same when Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated in 1991. Late at night, when the first information filtered in, we rushed to the transistor to hear Tully tell us the sad news.

Without Tully’s telling, these events didn’t really happen for us. It is a measure of how little we trusted AIR and Doordarshan that we only took Tully’s word for it. Not that we always liked what he said, and often the Establishment considered him biased against India. But we listened on because he filled the vacuum for news like no one else did.

Which of us doesn’t remember his reports on the Bhopal gas tragedy poisoning in December 1984 and its impact on those who live around the Union Carbide India factory there?

The last major event he reported on, which most of us remember, was the demolition of the Babri Masjid. Close your eyes, and for a moment you can hear his distinctive, slightly accented voice describe how he had witnessed throngs of men surge towards the mosque—while the police stood by—on that fateful 6 December 1992. While the government remained silent, Tully later said that the “authority of the government had completely collapsed’’.

These are selective memories from years of listening to Tully on the radio. But they do convey how Tully was trusted to tell us about us, whether we liked it or not.

By the late 90s, radio news had given way to live television news, and most of us tuned out, too. However, many of us stayed in touch with Tully through is books on India—No Full Stops in India being perhaps the best known. There were others: India in Slow Motion, India’s Unending Journey, to name just two.

It’s been a long time since we heard Tully’s voice breaking the news to us, but for those of us who grew up in the India of yesterday, we can still remember the solemn timbre of his voice as he broke it to us, even today.

The author tweets @shailajabajpai. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)