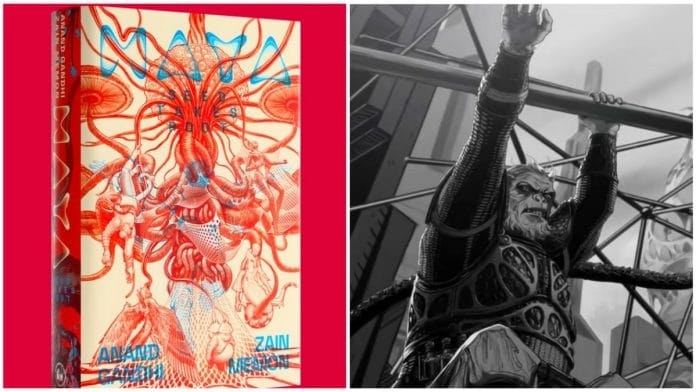

Optimism courses through filmmaker Anand Gandhi’s veins. Authentic, old-fashioned optimism that can believe — without a trace of irony — in changing the world through stories, and feels almost alien in 2025. MAYA, an in-progress “epic sci-fiction fantasy” trilogy that spans books, films, and games, is what that optimism looks like at scale.

Co-authored with Zain Memon, its first novel, MAYA: Seed Takes Root, opens with a riot. It’s a conflict between different species on the planet Neh — naags, manushyas, and crimson vaanars tasked with maintaining peace — whose agendas will unspool over the succeeding chapters of this fantastical world. But the riot is in pursuit of the oldest goal in the book: Power.

The trilogy’s themes are immediately apparent: social hierarchies, climate anxiety, regime changes, the march of time, surveillance states, parallel and simulated universes, and, inevitably, AI. These aren’t modest questions, and Gandhi and Memon aren’t approaching them modestly. The books are only part of what they have imagined as a “transmedia universe” that aims to encompass an audiobook narrated by British-Aussie actor Hugo Weaving, merch, and additional tomes that focus on the lore and built environments of the species.

It’s a challenging undertaking, but one Gandhi has been preparing for his whole life. His conviction rests on a specific theory of change: that fundamental questions about existence and equity can only be answered through storytelling.

“Only a few people have the privilege to continue questions like, ‘Who am I? Where do I come from? Where am I headed? How do we make the world beautiful and equitable for everyone?’ as adults,” he told me. “In a way, the job title in the East for this enterprise is the Buddha – essentially to take the greatest ideas and insights that we have at our disposal as a civilisation, unify and synthesise them, and deploy that knowledge toward creating prototypes for a beautiful future.”

The whole enterprise was funded by a recent campaign on Kickstarter, where the team set out to raise $10,000. They ended up overshooting their goal by 4,200 per cent, eventually raising over $420,000 from more than 4,100 eager backers. Those numbers are impressive, but they pale in comparison to the fact that Gandhi, Memon, and their team of over 200 collaborators — including evolutionary biologists, architects, neuroscientists, philosophers, artists, actors, and directors like Kani Kusruti and Vinay Shukla — have dedicated years to the project. And they are only getting started.

Also Read: Bollywood has a new Ramayana romance. All muscle and swagger

Moving to Goa to build MAYA

Grand scale has always been Gandhi’s playground. Most of his work has imbricated weighty ideas and themes, going down intense moral and ethical rabbit holes. His National Award-winning Ship of Theseus (2012), a deep meditation on identity and morality rooted in Greek philosophy, is still considered one of the most important independent films to have come out of India. Gandhi went on to co-write and serve as the creative director of the atmospheric horror Tumbbad (2018), while also helming projects like An Insignificant Man (directed by Shukla and Khushboo Ranka), ElseVR, a platform for VR documentaries, and the board game series SHASN, created by Memon.

But MAYA might be Gandhi and collaborators’ most ambitious moonshot yet. In 2018, tired of dealing with Mumbai, 35 members of their team packed their bags, and left the city for Goa. They now operate out of a gorgeous and placid seven-acre campus close to Panaji, where I meet them on a blazing afternoon. That’s an incredible leap of faith for a collective to take, but also clarifying to see just how passionately embedded everyone involved with the project is.

All great ideas, Gandhi insists, began life as stories.

“Democracy was a story once. The idea of equal rights is not guaranteed by nature. Money was a story that we agreed to early on. So we know that stories move the world, inform our beliefs and behaviour, and shift our choices,” he says.

But did those stories create the change, or did they emerge from movements that were already underway? Gandhi is betting everything on the former. If their stories could bring an audience to the “town square”, did they want to package and sell that attention to the highest bidder? Or could they use this attention toward making “civilisational shifts”?

The answer, Gandhi tells me, was yes, so long as the story was monumental, allegorically rich, and not limited to a certain period in history. “It had to be a story of all times, which has a good grasp on where we have come from, a map for where we are at, and a compass for the future,” he says. The result is MAYA, a mythology for the 21st century, a universe that is simultaneously familiar and alien, where meaning is an approximation of what we already know.

Also Read: Goa’s digital nomads get a reality check—working from paradise needs more than just good vibes

A new mythology, without good vs evil

Building that mythology has meant reimagining recognisable archetypes entirely. The species that the team — which includes Aayush Asthana, Shreya Dudheria, and Raju Chekuri — has created is built upon “all the wonderful things that are familiar to us,” Memon tells me. “We took the core visual archetype of what the garudas, the naags, the vaanars, and the rakshasis might be and rebuilt them from scratch.”

Each species was crafted with the help of evolutionary biologists and concept artists, down to details like what their vocal chords or cognition might look like. It’s meticulous work, obsessively detailed.

For instance, the manushyas are close to humans, and attempt to “tame” the environment through technologies. The rakshasis, meanwhile, have a malleable phenotype, and adapt to the environment they find themselves in. “We started using them as allegories of different social groups throughout history. So the garudas could be a stand-in for different power-bearing classes through history, while the vaanars would be the enforcers. Every culture draws its own meaning — each of them accurate, none of them perfect.”

In the first phase of the project, Gandhi and Memon have spent several years in world-building, simply setting the rules of how it works and the psychology of the characters. The crew plans to gradually open it up: first to their peers whose work they admire, and eventually to anyone who wishes to create their own versions from the source material. This has already translated into some genuinely novel collaborations that blur the line between fiction and reality. At CEPT University, architecture students are asked to imagine the built environments of MAYA as part of a graded programme. Another tie-up with New York’s Parsons School of Design is in the offing. The world is being built as if it already exists.

While each species is locked in competition, readers will have the chance to occupy the minds of both the protagonist and the antagonist. Building the universe has meant steering clear of the binaries of the “grand Western myth”, the familiar fight between good and evil. “We think that that is a very irresponsible way of painting the world we live in, because it necessitates that you are good and the opponent is evil and cannot be negotiated with. That creates a polarised world,” Memon says. “In India, we have the privilege of living in a non-canonical world.” MAYA is a chance to offer that Indian POV to international audiences.

The Indian approach, Gandhi and Memon argue, is especially suited to the problems MAYA takes on. What is past is prologue, and Gandhi says we can get past our technofeudalist moment by heeding warnings and “reverse engineering values from the future”. He directs me to a popular meme about the “Torment Nexus” — a term capturing how cautionary sci-fi ends up being created in the real world — to explain this.

Sci-Fi Author: In my book I invented the Torment Nexus as a cautionary tale

Tech Company: At long last, we have created the Torment Nexus from classic sci-fi novel Don't Create The Torment Nexus

— Alex Blechman (@AlexBlechman) November 8, 2021

But Gandhi and the team reject the cynicism embedded in that meme. Where most contemporary storytelling offers a view of the future we need to avoid, MAYA attempts to imagine one worth emulating. Whether that is naive or necessary depends on whether you think we are past the point where stories can do that kind of heavy lifting.

Gandhi and hundreds of his collaborators have bet on the opposite premise. It’s an extraordinary, audacious gamble — but at least someone is still optimistic enough to try.

Karanjeet Kaur is a journalist, former editor of Arré, and a partner at TWO Design. She tweets @Kaju_Katri. Views are personal.