Here is a trick question for this week: Is India a police state?

Three immediate responses could be: Of course not, regrettably yes, or, not yet?

You can also go ahead and add a “why”, how” and “when” to it.

The Oxford Dictionary definition of a police state is rather stern: A totalitarian state controlled by a political police force that secretly supervises its citizens’ activities. We aren’t there yet. But there are issues we can’t kick under the sofa.

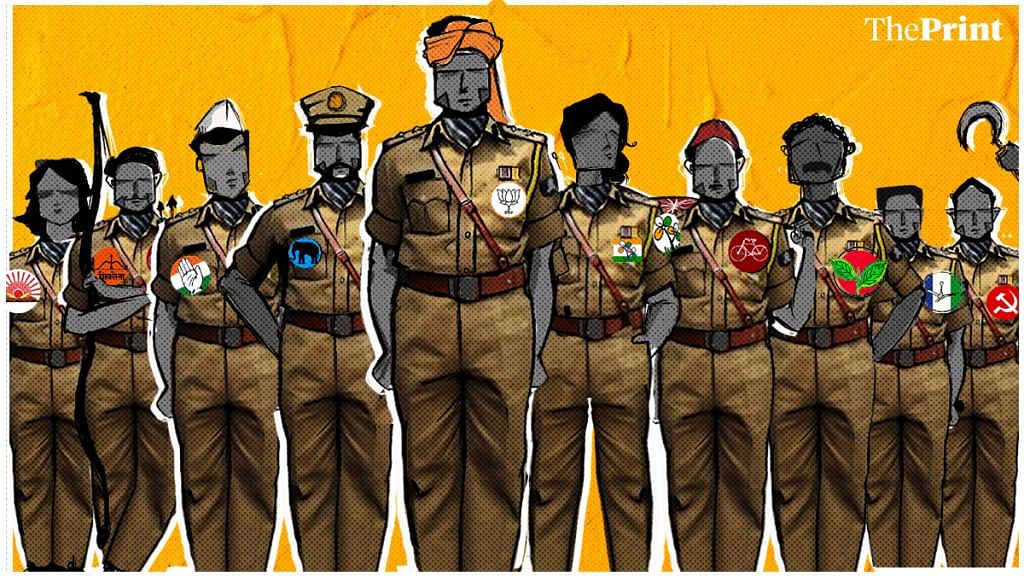

India may have not yet become a police state, but is becoming one where the police are a law unto themselves. The police-political nexus is now overpowering even the executive magistracy (IAS) and the judiciary.

Some recent and random pointers:

- The Tabrez Ansari case. The 24-year-old in Jharkhand was beaten to death by a mob on suspicion of bicycle theft. The police reduced it to a case of beating and assault and declared he had died not of beating (murder) but due to cardiac arrest. It took a team of conscientious doctors to call this fraud.

- Pehlu Khan “cow” lynching case in Rajasthan, where all accused were acquitted though they’d been caught on camera. The police never presented the full evidence, including the camera on which these videos were shot. The state government has ordered a re-investigation now. But when the police investigated and finalised the prosecution case, the BJP was still in power.

- Kuldeep Singh Sengar, the BJP MLA from Unnao, brazened out rape charges by a teenager. Rather than give her justice, police arrested her father who somehow ‘died’ in their custody. They had charged him, instead, with possessing illegal firearms. Now, after the suspected attempt to kill the girl and her lawyer caused an outcry, three policemen are also charged by the CBI as accomplices in the case.

- Delhi Police just registered a case of sedition against activist and Kashmir politician Shehla Rashid merely on the complaint of an individual. A citizen can be charged for sedition only by the state. Police registering sedition cases on private complaints makes a mockery of law and causes enormous harassment and legal expense to a citizen. It can also mean months spent in jail without trial, as with Kanhaiya Kumar. This happened, coincidentally, in the week that serving Supreme Court Judge Deepak Gupta said in a speech that criticism of government, bureaucracy or armed forces wasn’t sedition.

This list is by no means exhaustive.

It is true that the police are the favourite whipping boys when something goes wrong. Theirs is the most thankless job among our institutions of administrative governance. Over the decades, the political class has learnt to use — or misuse — them as uniformed mafias. But, is that all there is to it? Aren’t the police, their leadership, or the exalted IPS (Indian Police Service) also to blame?

We cannot imagine any of these cases ending up the way they did if a senior enough officer had applied his mind with some degree of honesty. It is criminal to pretend that it’s only the job of the courts to give justice. Any citizen, even a resourceful one, suffers for years as the process itself becomes the punishment. Then, there are cases where judges throw their hands up in frustration at the lack of evidence.

Our jails are filled with more undertrials than convicts. Many spend years in jail before they are acquitted or even discharged. We instinctively blame our courts and judges. But we hide from the elephant in the room: Our police service that is cowardly, callous and arrogant, complicit with the political masters, incompetent and rarely held accountable for the damage it does to the credibility of our system of law enforcement and justice. Of course, there are honourable exceptions now and then.

In so many years of tracking important or high-profile cases, ranging from corruption to mob lynching, we have rarely, if ever, seen an IPS officer either say, no boss, no case is made out here, so let’s not harass an innocent person just because you don’t like him or because you want to force him to defect to your party.

Nor have we seen anyone say, no boss, it isn’t an honourable thing for me to ‘fix’ an investigation or prosecution to protect someone you like very much. On the other hand, over the last many years, the IPS has become the most ‘committed’ service of the political masters.

The old heartland metaphor goes: If you leave it to the police, they can turn a rope into a snake (rassi ko saanp). Many cases lately, especially those of mob lynching in BJP-ruled states, also demonstrate that now they can also do the opposite: Turn a snake into a rope. Or, turn millions into billions in a corruption case (2G), billions into nothing (Ballary brothers), a lynching into a heart attack, an impoverished rape victim’s father into a hardened criminal, and a wild private complaint into a sedition FIR. Whatever might please the bosses.

The police-politician nexus isn’t a recent invention. But it has worsened dramatically in the last decade. It probably began with the Anna Hazare anti-corruption movement and the public anger it unleashed. Everyone wanted to send everyone else in power to jail, and all of a sudden it seemed there was only a policing solution to this.

The Jan Lokpal Bill, in its pristine original version, was a charter for a suspicious police state. Activists, the media, and most importantly the Supreme Court also bought into the idea. The CBI was now supposed to be the great corruption fighter this country had been waiting for.

The Supreme Court called it a caged parrot, and then decided to free it, but only in cases it had handpicked. The most shocking and counterproductive derivative of this was the abomination of “court-monitored” inquiries by special investigating teams. We use a description as strong as ‘abomination’ consciously as one of the judicial innovations accompanying this was the Supreme Court pretty much giving routine directions to trial courts, including to deny bail to the accused.

The results were disastrous. It made a corrupt and compromised police service more corrupt with extraordinary powers. Since then, three of the last four CBI directors have retired or been fired under the shadow of serious corruption cases. Of course, the two mega corruption cases because of which the courts and public opinion had given the police such powers went to pieces in the trial courts. Scores of innocent lives, some honest civil servants included, were destroyed, having spent months in Tihar as undertrials.

Thus began the “golden” era of police power. The UPA was using the same police force, the CBI, to target Amit Shah (then Gujarat’s junior home minister) and his loyal IPS officers in cases of alleged fake encounters. Such was the desperation that the CBI team, under instructions from the UPA, even tried to arraign the Centre’s own Intelligence Bureau head in Gujarat in the Ishrat Jahan encounter case.

Sure enough, on his retirement towards the last year of the UPA, the officer heading this investigation was about to be appointed vice-chancellor of a central university in reward for his ‘services’. Until some in the media exposed it and the Manmohan Singh government retreated. Meanwhile, the political winds were shifting. The same hotshot cops in the CBI sensed it, and it took no time for the cases to collapse. Our police cannot merely turn a rope into a snake, but also back into a rope, should the political ‘circumstances’ change.

We can go backwards and see the first signs of this professional collapse in the Jain hawala cases that P.V. Narasimha Rao filed to fix his rivals. This is when the CBI learnt the doctrine of ‘prosecution by leaks and character assassination’. Several promising political careers (including L.K. Advani’s) were stalled, some destroyed. By now, that doctrine of ‘character assassination by leaks’ has been perfected into a fine art by the CBI, and across our state police forces.

We know many young and sharp IPS officers who enter the service oozing idealism. In the course of time, however, they lose their way and focus, somewhere between wanting to be Singham but ending up being a cruel caricature of themselves like in Special 26.

No, India isn’t a police state yet. But Indian police, especially the IPS, has become our most politically compromised service. Beginning with the many pre-Independence doyens of IIP (Indian Imperial Police), the predecessor of IPS, the service has had iconic figures such as K.F. Rustamji, Ashwani Kumar, Julio Ribeiro, M.K. Narayanan, K.P.S. Gill, Prakash Singh, Ajit Doval, M.N. Singh and more who gave their service a moral and professional centre of gravity.

Today, there’s none and the IPS has reduced itself, most regrettably, into the Indian Political Service.

Also read: Unnao rape accused Kuldeep Sengar ‘unusually quiet’ in Tihar jail, keeps to himself