Twentieth century on, the world has seen numerous uniformed dictators. No country, however, has produced as much innovation in military rule as Pakistan.

The latest, now that the notification anointing Asim Munir Army Chief and Chief of Defence Forces for five years has been issued, is the most breathtaking. Any Pakistani cadet who steps into the academy can aspire to become the country’s ruler. Yet, Munir has now pulled a stunning innovation, incredible even by Pakistan Army’s standards.

See it this way. None of Pakistan’s 29 prime ministers in 75 years (Liaquat Ali Khan was the first) has completed a five-year term because the Army wouldn’t let them. And yet, Munir has got his current prime minister to appoint him CDF for five years.

It isn’t an irony or absurdity to laugh at. This is a military dictatorship’s innovation equivalent of what Tesla or Palantir might have achieved in tech domains. First Munir persuaded the Sharifs to appoint him chief a day before his retirement while the incumbent (Qamar Javed Bajwa) was in service. As a result, Pakistan had two serving chiefs for two days. Now, his three-year tenure ended on November 28, so he retired that day, but continued to be chief nevertheless for a week when the notification appointing him CDF and Army chief was issued. I presume it is retrospective or some auditor might object to his salary for the week when he had no job. Of course, it will be a recklessly cheeky auditor.

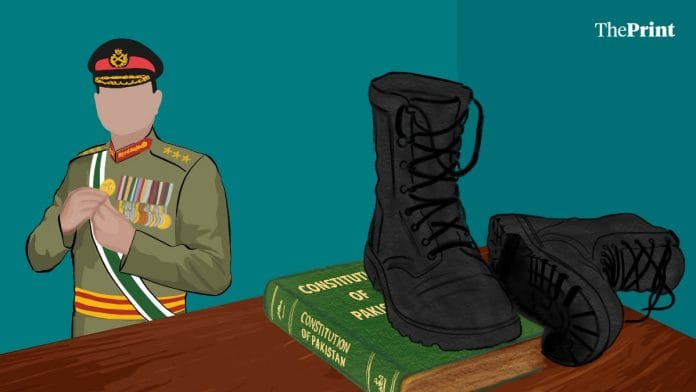

Please stay with me. He first rigged the 2024 election by jailing Imran Khan and his wife, barring his party from contesting and then installing Shehbaz Sharif as prime minister of his choice. Now, he got the same prime minister to first promote him to field marshal, then mutilate his republic’s constitution through the 27th amendment, making the field marshal’s job for life, creation of the CDF as the boss of all armed forces with a five-year tenure and lifelong immunity from any prosecution. A two-year extension was thrown as a bone to the air chief, already serving an extended term since March, 2024.

Also Read: How Pakistan thinks: Army for hire, ideology of convenience

To summarise: the general became field marshal for life with immunity, then CDF for five years after the completion of his three-year tenure as chief—all through an elected prime minister, parliament, and the constitution, amended by members elected in an Opposition-free election. The latest in Pakistan’s history of military dictators is consecrated by its constitution, parliament and notified by its prime minister and president. This is like the two men elected to the country’s topmost positions signing political death warrants for themselves.

This, the civilian government inviting the general into power, isn’t unprecedented in Pakistan. In 1958, civilian President Iskander Mirza imposed martial law, appointed General Muhammad Ayub Khan as his Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA). Now, Ayub fired Mirza, became president and appointed a nondescript, non-threatening general Muhammad Musa Khan as army chief under him. But how could a general report to him, also a general? He promoted himself as a field marshal. Musa lasted until 1966. This also set off the process of Pakistani army chiefs having long tenures. For comparisons, Pakistan has only had 17 army chiefs to India’s 31st now. By the time Munir finishes this term in 2030, India will have its 33rd.

Ayub-invented party-less, ‘guided democracy,’ held a sham election and ensured even the defeat of Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s sister Fatima. He handed over to General Yahya Khan. Yahya’s hybrid included Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto as foreign minister. He held an election, too. But because the “wrong” side, Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League, won, he tossed away the results. After him, Bhutto experimented with martial law briefly in 1977 but General Zia ousted and jailed, and executed him. Zia subsequently tried ushering in an Islamic regime (Nizam-e-Mustafa), then a party with less democracy through a staged election and then fired even the prime minister, Mohammed Khan Junejo, so elected. History was denied of more ‘imaginative’ ideas from him with that C-130 crash or bombing in Bahawalpur, 17 August, 1988.

Since then, either a general has been directly in charge (Pervez Musharraf, 1999-2007) or controlling power from outside, or rather leading from behind, routinely cadging extensions. Until Munir came with a new, improved script.

We avoid going into greater details of the many colourful arrangements in Pakistan and take this argument to the larger Subcontinent. That far from inspiring other military strongmen in the Subcontinent, the Pakistani example has persuaded them to go the opposite way. As we now see, all have eschewed political power and backed their democracy. We are talking about Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Maldives. Even in Bhutan, the monarch has brought in a fairly elected government and ceded significant power to his elected prime minister. They’ve all rejected the example of Pakistan.

Also Read: India doesn’t give walkovers to Pakistan in war. Here’s why it shouldn’t do it in cricket either

They are all safer, stabler and already twice (Bangladesh), two and a half times (Bhutan), thrice (Sri Lanka) or eight times (Maldives) as prosperous per capita as Pakistan. Even Nepal has caught up and will soon leave Pakistan behind, given its slightly higher GDP growth rate and much lower birth rates. Pakistan is the champion loser in the Subcontinent because competitive politics, democracy, however messy, yield better outcomes than dimwit military dictators.

In each country, generals had their opportunities. In Bangladesh, two generals did rule. But the circumstances and context of General Ziaur Rahman’s takeover in 1977 were unique. It was rooted in the contested history of the Bangladesh liberation war. While Mujib was imprisoned in West Pakistan, Zia, then a major, led the rebellion along with fellow young Bengali officers on the night of the Pakistani crackdown (Operation Searchlight), March 25, 1971, shooting his East Bengal Regiment’s Punjabi commandant Lt Col Abdur Rashid Janjua. He believed he proclaimed the new republic in a wireless radio broadcast at 7.45pm, March 27, way earlier than Mujib. Mujib had just been arrested and taken to West Pakistan.

Mujib, too, took a dictatorial turn and his assassination and multi-stage military takeover was led by relatively young officers. Zia, now chief, took over in 1977 and was assassinated by young officers in 1981. After a brief civilian interregnum, General H.M. Ershad ruled (1983-90) but ultimately, democratic pushback destroyed him. All major parties, notably arch rivals Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia, joined hands to oust him and restore democracy. Convicted for corruption, he did jail time. Bangladesh recovered from these hard knocks and its army, having learnt its lessons, became a guardian of democracy.

Over the past two years, we have seen street protests throw out deeply unpopular and elected governments in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal. In each, a general could have easily taken over. Instead, they all employed the army to bring reassurance amid chaos, while supporting peaceful civilian transition and elections. In Bangladesh, the country most likely to be influenced by the Pakistani military, the most political statement you’ve heard from its chief is a gentle nudge once that elections should be held sooner than later.

That’s the three-example rule in journalism. In the exact period that Munir has been consolidating power, his counterparts in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal have eschewed it with remarkable dignity and professionalism. Each of these countries is doing better than Pakistan. And if your country is doing so much better, so what if nobody (not even I, who should) can remember the name of its army chief. The downside is, Donald Trump wouldn’t hail your chief as his favourite field marshal. Isn’t that something to celebrate?

Also Read: For Indian Mercedes, Asim Munir’s dumper truck in mirror is closer than it appears

Shekar, stop writing about Pakistan! They are a lost cause. I would appreciate if the funding is put in to the development of India against Chinese economy and military aggression. I don’t see a point in analyzing a nation that is going no where. China, has transformed itself in to a global power. I want us to get compared, criticized and show a path to becoming China.

Pakistan is scripting its future and destiny. Its economy remains a soft spot. With all the power of the armed forces ( three services ) and the civilian government, General Munir has no solutions. If there is popular discontent, that opprobrium will travel to him. 2. As far as India is concerned, for better or worse, there is now one clearly designated individual to talk to. Not Shehbaz Sharif. Unless there is a desire to let things drift to war, it may be time to start a limited dialogue, to stabilise what has become a very fraught situation.