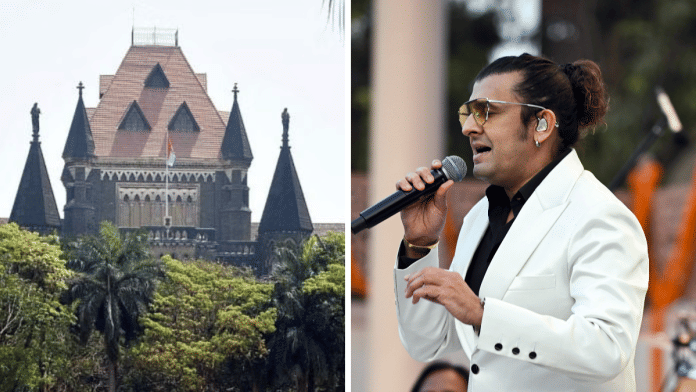

New Delhi: In a significant ruling on digital impersonation and personality rights, the Bombay High Court has passed a restraining order against a social media user who was impersonating singer Sonu Nigam on X.

Sonu Nigam Singh from Bihar has been posting politically and communally charged content under the name ‘Sonu Nigam’, creating confusion among users and generating a backlash against the singer. The court order, made public 15 July, directed the man to display his full name.

Sonu Nigam Singh, a criminal lawyer from Bihar as per his X profile, had been operating an account using the name ‘Sonu Nigam’, sharing content of political and communal nature, causing public backlash against the singer, who officially quit X in 2017. He maintains a verified social media presence only on Instagram.

Singer Nigam approached the Bombay High Court alleging Singh was violating his personality rights by using his name to share sensitive content, without clarifying his own identity properly. The suit was filed under the Commercial Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) law.

The singer’s counsel informed the court that Singh had gained over 90,000 followers — including public figures like Prime Minister Narendra Modi and former Union minister Smriti Irani—by exploiting the singer’s name.

Justice R.I. Chagla Friday passed an ex-parte interim order directing Singh to clearly display his full name on the platform to avoid further misrepresentation.

The court explained how “the unauthorized use and/or commercial exploitation” of the Nigam’s name by the impersonator has not only associated the singer’s “name and persona with ignoble acts” but also severely damaged his reputation.

Advocate Hiren Kamod, who represented the singer, told the court that Singh had amassed over 90,000 followers by leveraging the singer’s name. Kamod also submitted 14 examples of communally provocative posts made by Singh which, he claimed, harmed Nigam’s reputation.

Also Read: Kannada film body boycotts Sonu Nigam over Pahalgam remark, demands apology

The posts

One of his posts was about legendary singer Mohammed Rafi. The post loosely translates to, “Mohammed Rafi was a devout Muslim who offered prayers, yet he sang bhajans (devotional songs) in such a way that it felt like a Hindu was singing. How was he able to bring such a transformation in his singing? Singing and listening to bhajans purify and discipline both the heart and mind. This is its positive impact.”

A separate post in reply to a tweet read, “Dear @cartoonistrrs ji, loudspeakers are not a problem. The problem is crowing like a rooster, giving a sermon at 4 a.m. from Delhi to Noida. As for the pain you’re experiencing — the cure for that isn’t in medical science, it’s in spiritual science.”

A third one, also cited in the official order, reads, “Every Indian going to Türkiye is a traitor. That’s the tweet. Period!”

The Article 21 balance

Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees the freedom of speech and expression to every citizen. The Bombay HC, while acknowledging this right, noted that this is not an unbridled or unfettered right.

Courts in India have held that reasonable restrictions must be placed especially when the exercise of the right leads to “misrepresentation and violation of the right of others”.

The court noted the singer’s right to privacy, which includes a ‘right to be let alone’ (essentially meaning freedom from interference) is protected by Article 21 of the Constitution.

“Even though the Plaintiff is a celebrity, as a citizen of this country the Plaintiff is entitled to safeguard the privacy of his own and his family and to prevent the publication of any content in the media/social media which violates this right,” the court said.

What are personality rights?

Personality rights or the right of publicity refer to an individual’s right to control the commercial use of their identity—including their name, image, likeness, or other aspects that uniquely identify them. These rights are especially significant for celebrities and public figures whose names carry commercial value.

In this case, the court explained singer Sonu Nigam’s “personal/real name, which is also the stage name; his image, photograph and likeness… are all valuable and protectable facets of the Plaintiff’s personality rights and publicity rights.”

Although India does not have a specific statute governing personality rights, they are recognised under the broader framework of right to privacy (Article 21) and the provisions within intellectual property laws like the Copyright Act.

Nigam’s case also brings into focus the ‘principle of passing off’ under trademark law which is used to stop someone from misrepresenting their goods or identity in a way that causes confusion and unfairly benefits from another’s reputation.

Even if a person’s name or image is not formally trademarked, if that name has commercial value or public recognition, using it without permission in a misleading way can qualify as ‘passing off’.

Here, Sonu Nigam Singh’s use of the name ‘Sonu Nigam’ misled users into believing the posts were from the singer, amounting to false endorsement and reputational damage — both grounds under ‘passing off’.

Additionally, under IPR laws, celebrities—especially singers, actors, or artists—are protected through performers’ rights. These include the right to attribution which is the right of being recognised as the performer. These rights ensure that a performer’s identity and work are not misused or altered in a way that harms their image or dignity.

Former Indian cricket captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni was caught in a similar situation with 4-5 accounts claiming to be that of the ‘Captain of the national cricket team’ operating on Twitter (now X) in 2009.

These accounts had more than 4,000 followers back then, leading to misunderstanding and confusion. Later, Dhoni’s agents and family members made it clear that he has no official Twitter account.

A landmark order for Digital Identity Protection

Delhi-based Intellectual Property Rights advocate Ruchika Yadav told ThePrint how personality rights have been recognised and safeguarded by courts for a while now. “Over the years, the ambit of protection has been enlarged by the courts, and it is fairly established that a trademark registration is not a prerequisite for a celebrity to protect their name or image against unauthorised use by third parties,” she said.

She added, “This recent Bombay High Court order certainly expands the scope of personality rights and is different in the sense that the Defendant here was using his own name. In clear cases of impersonation, the IT Rules would require blocking the social media accounts. However, here the interim order calls for the Defendant to use his full name, thus indicating a balancing attempt on part of the court.”

The Bombay High Court’s order signifies how a well-known name can be protected under personality rights, even without trademark registration.

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)