New Delhi: Two decades after the Supreme Court mandated crèches, education and child-friendly conditions in prisons, implementation of the order remains inconsistent, leaving children of incarcerated parents as one of the most neglected groups in India’s criminal justice system, a new study has found.

The study by iProbono, a women-led social justice organisation, found that lack of crèches, absence of proper data and severe gaps in awareness about welfare schemes continue to plague the prison system’s ability to support these children.

“The children of prisoners are invisible victims of crime and the penal system. They have done no wrong, yet they suffer the stigma of criminality. Their rights to nurture are affected by both the criminal action of their parents and by the state’s response to it in the name of justice,” the 38-page report said.

A total of 1,537 women prisoners were accompanied by children inside prisons between December 2023 and March 2025, according to the study, which extracted data from 32 Right to Information (RTI) queries filed in ten states and a Union Territory.

But, the report said, this figure does not capture the far larger undocumented population of children living outside prison walls after a parent’s arrest, incarceration or separation at the age of six.

The report, titled ‘Welfare of Children of Incarcerated Parents’, also drew on responses from child welfare committees, departments of women and child development or social justice, and national institutions including the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and National Commission for Women (NCW), and supplemented its findings with academic research, government schemes and NCRB prison statistics.

Also Read: Delhi Bar Council has rarely had women members before. This time, the mould is ready to break

Three invisible categories

Children of incarcerated parents (CoIPs) fall into three categories, the study noted. The first includes children up to six years living with their mothers in prison, usually due to lack of alternative care options. The second covers children outside prisons—those left out from the time of their parent’s arrest or transitioned out after reaching age six. And the third comprises children living with the remaining parent, other caregivers, in child care institutions or on their own.

Broadly, the report found that children of incarcerated parents are neglected by the system despite existing safeguards and policies. This stems from systemic gaps, economic stress, isolation, denial of basic rights, disrupted childhoods and the stigma attached to them.

“These children are punished for crimes they did not commit,” the report said, adding that there is little data on the topic.

For children living outside prisons—whether with caregivers, in institutions, or on their own—systemic safeguards are virtually non-existent, the report said. Data on education, safety and access to welfare schemes, too, is largely unavailable across states.

Infrastructure deficits

The Supreme Court in 2006 ruled in the R.D. Upadhyay vs State of Andhra Pradesh case that female prisoners can keep their children with them until the age of six, after which they should be handed over to suitable surrogates or sent to institutions, with weekly visitation rights for the mothers.

The court mandated that prisons should have a crèche for children below the age of three and a nursery for children below the age of six, with separate provisions for food, clothing, drinking water and medical care.

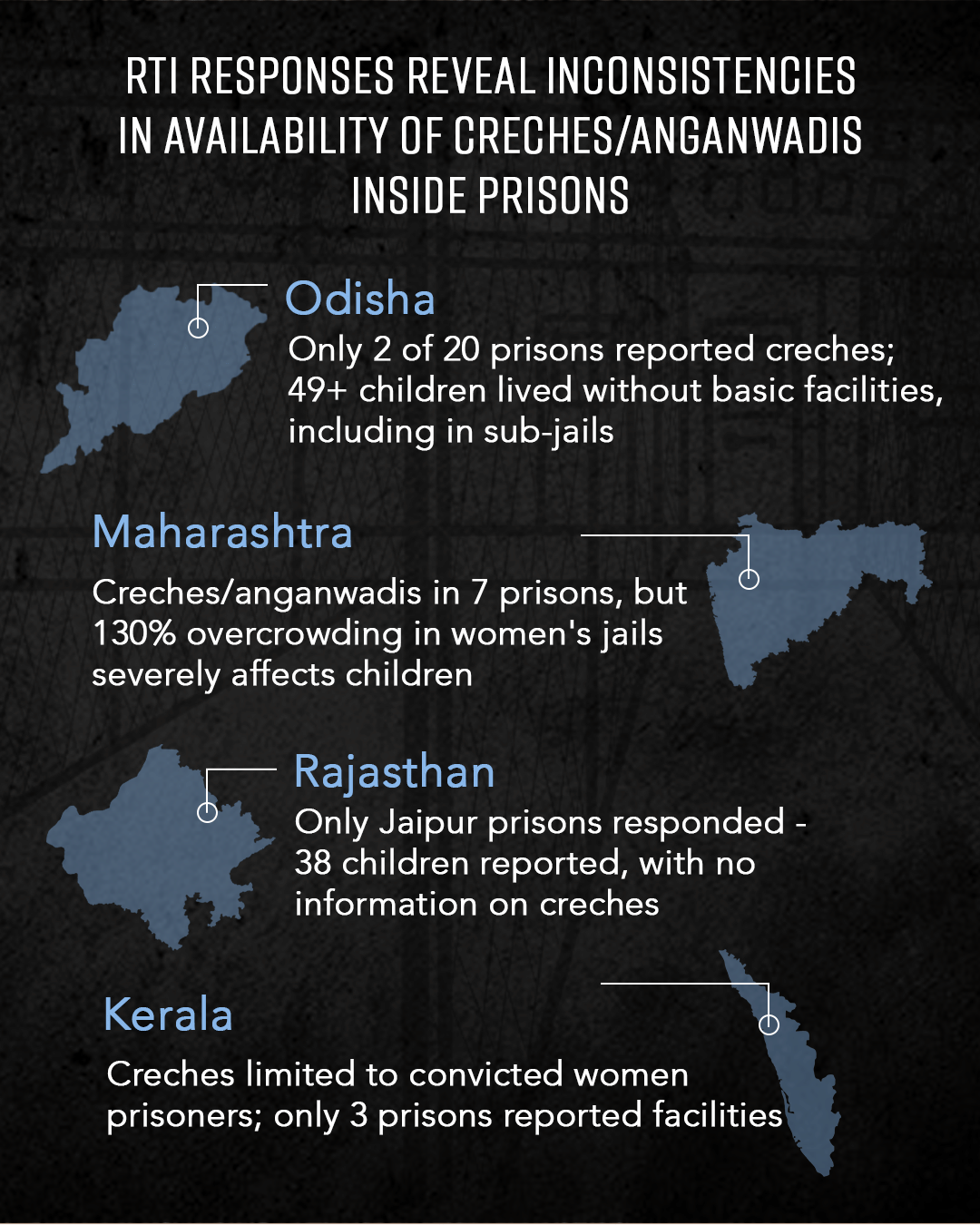

Yet the study found stark implementation gaps. In Maharashtra, the report said, there were anganwadis or crèches in just seven prisons.

Adding to the issue is overcrowding, with women’s jails logging occupancy at 130 percent. This, the report said, would have severely impacted the quality of life for children living there.

In Odisha, only two of the 20 prisons reported having crèches, while at least 49 children lived without facilities. In Rajasthan, the only available data was for Jaipur prisons, which reported 38 children living on premises but provided no information about crèches.

Kerala provided crèche facilities only for convicted women prisoners, with just three prisons reporting such amenities. Several prisons failed to maintain even basic records of children living inside, the report said.

Children also continue to live in sub-jails without adequate facilities for education and clothing, the study found. Sub-jails are smaller correctional institutions located at the taluka or sub-divisional level. These are designed to hold prisoners for shorter periods or while trial is ongoing.

Welfare schemes unutilised

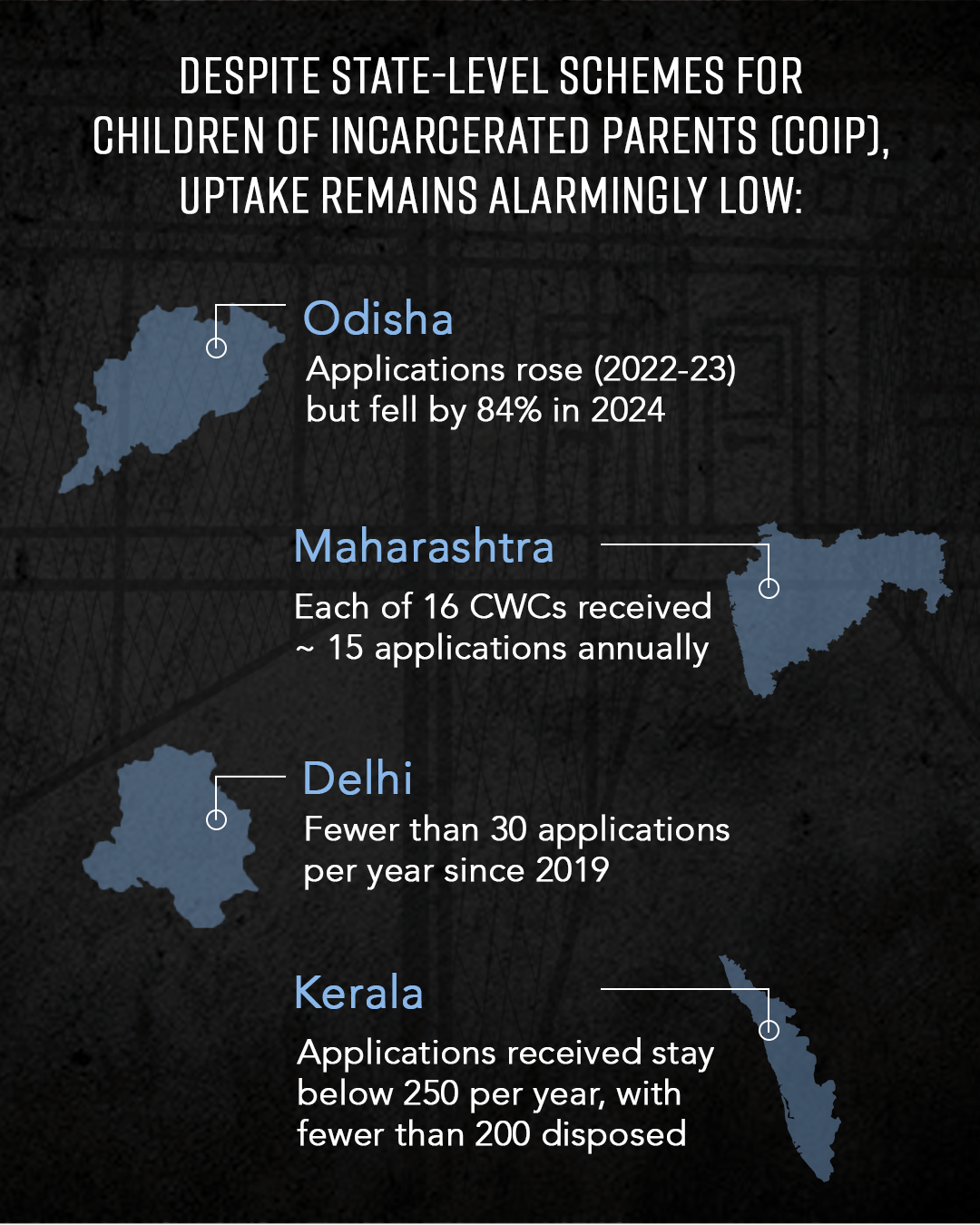

Although some states have introduced schemes for children of incarcerated parents, their implementation remains inconsistent and often ineffective, the report said.

In Delhi, RTI data from six CWCs showed very low uptake of the Scheme for Financial Sustenance, Education & Welfare of Children of Incarcerated Parents, 2014.

The scheme was introduced following the Delhi High Court’s ruling in Birndavan Sharma vs State (2007) case, in which the court directed the ministries of social justice and empowerment, and women and child development to frame a scheme to ensure appropriate funding for the education and welfare of such children.

Under the 2014 scheme, children whose parents were in jail were entitled to monthly financial assistance of up to Rs 3,500 per child, along with education support such as admission to the nearest government school. If the child was already enrolled in a private school, the scheme provided for full waiver of tuition fees or any other charges, in addition to free books, uniform and copies.

The scheme also entitled such children to counselling and safe, comfortable living arrangements, with first priority given to the child’s own home and family, then to relatives, and institutions only as a last resort.

But, the report found that until 2023, only 30 applications were filed under the scheme and 24 were disposed of. Since 2019, applications to the scheme have averaged fewer than 30 a year, the study said.

In Odisha, out of 31 CWCs, only 19 responded to RTI requests. In 2022, 486 applications were received under the state government’s Guidelines for Welfare of Children of Incarcerated Parent Scheme, 2022. This figure rose to 823 in 2023, only to drop by 84 percent to just 131 requests in 2024.

Rajasthan’s Department of Child Rights reported 528 applications under the Palanhar Yojana, launched in 2022. Of these, 414 applications were disposed of, resulting in foster-care placements as required under the state’s scheme.

In Maharashtra, under the Krantijyoti Savitribai Phule Bal Sangopan Yojana, 2023, each of the 16 CWCs received about 15 applications per year on average, indicating moderate but stable uptake.

In Kerala, the number of applications under the Educational Assistance To Children Of Prisoners scheme remained below 250 every year, raising concerns about lack of awareness among families and authorities. Onerous documentation requirements, the report said, was another recurring issue across states.

Path to reform

The report noted the absence of a single nodal authority, uniform data system or statutory recognition ensuring the protection of children of incarcerated parents.

“The justice system addresses crime but it repeatedly fails the children left behind,” the report said, outlining recommendations to remedy the situation.

The first step, it suggested, should be statutory recognition of children of incarcerated parents as a separate vulnerable group. Following this, a designated nodal authority must be established to ensure accountability and coordination.

Uniform data collection across prisons, CWCs and child protection agencies could also help such children, the report said, pointing out that targeted outreach can ensure greater access for families to existing schemes. Finally, it said, the Supreme Court guidelines must be implemented in a proper manner.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)

Also Read: 4-yr-old boy ‘locked in dark room, tortured’. Delhi kindergarten horror in French embassy premises