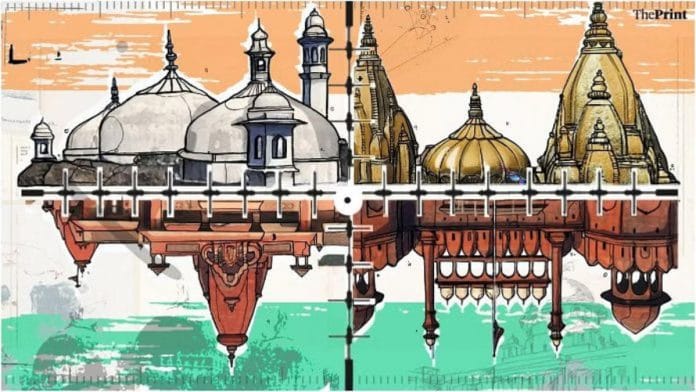

New Delhi: The battle over the legality of the controversial Places of Worship Act (POW) has drawn an unusual mix of petitioners—a Naga sadhu-turned-lawyer, “descendants” of Lord Rama, sitting lawmakers, political leaders, saints, academics and historians.

With more than 2,000 pages of documents, the case challenging the constitutional validity of the special 1991 law—which bars lawsuits seeking to reclaim places of worship or change their status as of 15 August 1947—is more complex than the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid land dispute resolved by the Supreme Court in 2019.

Eight writ petitions—five seeking to strike down the law and three supporting it—are pending in the top court. To add to the legal quagmire, another 16 intervention applications are challenging the law and 40 are demanding its retention.

Writ petitions are substantial legal pleadings filed under Article 32 to remedy an executive or legislative wrong that violates a person’s fundamental rights. Intervention applications are supportive pleadings. Unlike a writ petitioner, an intervenor is not required to make comprehensive arguments during their case hearing.

Last week, an exasperated two-judge bench led by Chief Justice Sanjiv Khanna, rebuffed the numerous applications that have piled up in the POW matter and discouraged new parties from joining the litigation.

“Enough is enough. There has to be an end to this,” CJI Khanna said during the hearing, asserting that the three-judge bench hearing the case would not entertain any new petitions.

While adjourning the hearing to April, the bench observed it would not accept any more petitions or applications as the growing number of petitions was preventing the Centre from taking a stand in the case.

Despite eight opportunities in the last several months, the Modi government has not yet filed its response to the petitions seeking the revocation of the 1991 law. The central government is also a respondent in the cross-petitions filed on the law.

Complex legal fight

The POW Act has faced legal challenges since 9 November 2019 when a five-judge Supreme Court bench concluded the decades-old litigation between the Ram Temple Trust and the Uttar Pradesh Sunni Waqf Board by ruling that the mosque at the disputed site was built after pulling down a temple. It decided in favour of handing over the land to the trust for the construction of the Ram temple.

Though the Ayodhya case file was a compilation of over 4,000 documents, the arguments were limited to historical facts and evidence presented to the court during the trial.

But the petitions in the POW case go beyond history and argue that the case infringes on constitutional rights, including equality as well as religious and cultural freedom.

Both sides have invoked the principle of secularism to bolster their arguments, besides relying on various provisions of the Constitution to support their case.

Petitioners opposing the law, mainly Hindu groups, cite scriptures and religious texts to argue for the importance of temples. Their argument includes lists of temples allegedly destroyed and converted into mosques.

In contrast, the POW Act’s supporters have extensively drawn on Parliamentary debates that led to the passing of the law to reinforce its continued relevance today.

Legal challenges and key petitioners

The validity of the POW Act faced legal challenge within a year of the Supreme Court’s Ayodhya verdict. This is despite the five-judge bench observing that the 1991 law was a legislative instrument meant to protect the secular features of the Indian polity, a basic feature of the Constitution.

Three petitions were filed in 2020—two in June and one in October—to quash the law. A Lucknow-based Hindu organisation, the Vishwa Bhadra Pujari Purohit Mahasangh, and then BJP MP Subramanian Swamy approached the court in June, while Supreme Court advocate and former BJP spokesperson Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay filed his plea later.

Upadhyay’s petition was the first to be heard in the Supreme Court, which on 28 October 2020 issued notice on it, opening the window for a legal debate on the POW Act.

The three petitions argued the 1993 Act was an affront to their constitutional rights as Hindus. It violated their rights to religion, culture, equality, sovereignty and dignity. They also sought quashing of the law on the grounds that it legalised illegal structures opposed by generations of Hindu families.

Two years later, in September 2022, two fresh writ petitions were filed to quash the POW Act. Naga sadhu-turned-lawyer Karunesh Kumar Shukla and Anil Kumar Tripathi, an advocate, joined the chorus against the law.

Between 2022 and now, 16 intervention applications have been filed in support of the five writ petitions. While two petitioners say they’re “descendants” of Lord Rama, the others are Hindu organisations that argue Hindus have the constitutional right to assert their religious identity.

One petitioner termed the demolition of temples as a “barbaric act.” Since temples are connected to the collective identity of Hindus, the POW Act is an affront to this “collective identity,” he argued in his application.

The “descendants” of Lord Rama—Jagdish Prasad Sagar from Delhi and Anupam Prakash Maurya from Kangra, Himachal Pradesh—said the POW Act has taken away their right to approach the court to undo the “religious injury” caused to Hindus, Jains, Buddhists and Sikhs by invaders.

Claiming to be “very religious, spiritual and devoted persons” they said the act is also against the principle of secularism, which is part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

Maurya also claimed that Hindus would have been denied justice if the Ayodhya case had remained undecided.

Sagar, on the other hand, challenged the Act on the grounds it was a violation of Article 14 which promises equality to all. He said the law’s exclusion of the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid dispute was discriminatory as it did not extend to Mathura, the birthplace of Lord Krishna. Since both are incarnations of Lord Vishnu, the creator, the government should not have made such an exception.

The Shri Krishna Janmabhoomi Mukti Nirman Trust has taken a similar stand in its application against the POW Act. “Excluding similarly situated two places of worship and pilgrimage is arbitrary, discriminatory, and contrary to Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution,” it said.

The other applicants opposing the law are organisations such as the Hindu Shree Foundation, Akhil Bhartiya Sant Samiti and Ganga Mahasabha, established by freedom fighter Madan Mohan Malviya.

Prominent intervenors are Mohan Guru Amrute, a monk heading the Shri Krishna Ashram in Amravati, Maharashtra; Swami Avadheshanand, head of the Juna Akhara; Swami Ravindra Puri, president of the Akhil Bharatiya Akhara Parishad and the Mansa Devi Mandir.

According to them, the law violates secularism because it favours one community over others, and even contradicts the Vedas, the Puranas, the Ramayan and the Bhagavad Gita that say an idol represents the “Supreme Being” and its existence is never lost.

They argue that since a deity cannot be divested from its property even by a ruler or king, Hindus have a fundamental right under the Constitution to worship the deity at its original site.

Moreover, while restrictions on the right to acquire a religious site can be stopped by law only on the grounds of public order, such limits cannot operate permanently if they block the lawful exercise of fundamental rights by devotees they argued.

Defence of the Act

For more than two years after the petitions against the POW Act were filed in the Supreme Court, nobody opposed them. That changed in September 2022 when a Muslim body Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind approached the court through a writ petition supporting the law.

In the last two years, the number of petitioners and intervenors defending POW has swelled to 42. The list of applicants includes former bureaucrats, political parties, parliamentarians, historians and retired police officers.

They have appealed to the top court to maintain the status quo, arguing that the 1991 Act was enacted by Parliament to prevent communal disharmony.

The applicants have also pointed to the surge in litigation in the last two years to reclaim sites where mosques are located.

An application by retired bureaucrats and police officers, including Wajahat Habibullah and Julio Ribeiro, has challenged the arguments against the POW Act, arguing that they are based upon a “disingenuous description of history”. They also contend that the “prayers are pernicious discourse set out in the petition” as they use the expression “invaders” to describe Muslim rulers.

Some have questioned the glorification of the “Hindu faith” in the petitions opposing the POW Act.

“In any event, the Adivasis and other animist forms of worship were of even greater antiquity, but the age of a faith is irrelevant in the Constitutional scheme,” said one of the intervention applications.

Since freedom of conscience under the Constitution is not absolute and is subject to restrictions on the grounds of “public order, morality and health, the POW law is a lawful restriction on the freedom of conscience”, it added.

Another group of former bureaucrats and writers such as retired home secretary G.K. Pillai and former Delhi Lieutenant Governor Najeeb Jung, argues that the current litigation is an attempt to abrogate the POW law through the judiciary, a move Parliament has refrained from making in the last three decades.

“Facets of history have been deliberately painted in communal colour and grievances of the petitioner concerning the actions by ancient rulers cannot be adjudicated by the judiciary,” they said.

Jitendra Satish Ahwad, a legislator from the Mumbra-Kalwa constituency in Maharashtra, recalled the Mumbai riots in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid mosque demolition in 1990. He warned against the revocation of the POW Act, claiming it would disturb the efforts to foster harmony following the large-scale violence.

Political leaders and lawmakers such as Manoj Kumar Jha from Bihar, Thol Thirumavalavan from Tamil Nadu and social activists, including Tushar Gandhi, said it would be “unwise to lift the bar” on bringing about litigations on religious places of worship.

Historians and scholars, including Purushottam Agarwal, Neeladri Bhattacharya, Pankaj Jha, Radha Kumar and Jaya Menon have argued against the adoption of legal recourse to undo “historical wrongs committed by past rulers.”

“It has been further held therein that our history is replete with actions that have been judged to be morally incorrect, that contemporary legal mechanisms should not become instruments for settling ancient disputes,” some historians have noted in their applications.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Modi govt yet to make stand clear on Places of Worship Act, chorus to scrap law grows in BJP, RSS