Jaipur/Jodhpur/Barmer: Traffic jams and Jaipur had been oxymorons for me, till I found myself back in my hometown on a reporting assignment last month.

As my car inched forward in the city’s snaking traffic on Christmas Eve, it seemed half the country was holidaying in the Pink City.

Soon, my photojournalist colleague and the exasperated driver had started abusing my dear Jaipur. The driver joked: “Khana pet kharab kar deta hai aur traffic dimag. Phir kehte hain padharo mhare des (the food upsets your stomach and the traffic drives you insane, and then they say come to my state — a reference to the popular Rajasthani folk song, Kesariya balam).”

The insult to my city seemed like a personal attack to me. Fuming, I turned my face to the car window to look at the city, only to realise that the massive lifestyle changes that Jaipur had witnesses since 2014 — the year I left the city — had made it almost unrecognisable to me.

When Jaipur got a night life

The most fascinating aspect of the new Jaipur for me was its nightlife — the city that I remembered would fall asleep by 9 pm.

The area around the Nahargarh Fort — once notorious for groups of men riding around on bikes, bottles of Tuborg in hand, after dark — is now spectacular at night. Back then, the fort would be closed to visitors by 5 pm. But the time has now been extended till 9.30 pm, allowing visitors a night-time feel of the fort, with its cannons and rooms, once occupied by the royalty.

From a neglected fort infamous for young couples looking for corners to make out, it today overflows with tourists and vendors selling guava, milk and chaat. The promenade in front of Jai Mahal has also been developed beautifully, with the palace gleaming at night and both tourists and local residents enjoying ice creams and the view.

The other city attraction, Hawa Mahal, too, looks dazzling in the evening. The bustle and congestion of the old city around it seem to fade out as one pauses to look at it. “I often come here at night now, after peak hours, and just enjoy the view. The lighting has also made the area safe for us to leave our houses at night,” a resident told me.

The beautification and development of the city’s tourist draws has come at a cost though. The local residents’ favourite picnic spot (Nahargarh), which I remember visiting as a child with my family — we would carry with us boxes packed with aloo poori — and later, for bike rides with friends on days when we bunked school, doesn’t quite belong to the Jaipur wallahs anymore.

A new cafe culture

There has been a boom in the number of cafes in Jaipur since I left in 2014. I can say it with a certain degree of confidence because, before that year, there was hardly any “cool cafe” to hang out at. But the cafe’s and bars today can give some setups in Delhi a run for their money.

Cafe Lazy Mojo is among the new-age cafes to open up in Jaipur — five more have now sprung up in the very lane in which it is located. A little further ahead, right in front of the city’s World Trade Park, a cluster of cafes and eating joints has become one of the most popular hangout spots for the youngsters today. Gone are the days when the Gaurav Tower mall was the only “fun place” for the youth in the city.

The business owners have made perfect use of the city’s many heritage properties, converting them into restaurants, cafes and bars, to give an added edge to their establishments.

The one I especially liked was Chirmi in the city’s C-scheme area — a bar overflowing with the Jaipur elites. The vibe here was similar to Delhi elites mingling at an upscale South Delhi pub. The place also doubles up as a hostel.

It’s one of the few bars set in one of those palatial, heritage properties that someone with an average salary can afford.

The Jaipur public has also slotted the city’s cafes by “purpose of meeting”. Friends in the city told me Fort cafe in Jaipur’s Malviya Nagar is the new ‘it’ place for rishtas — when prospective bride and grooms (and possibly their families) meet, to check out the chances of an alliance.

Also read: Escape from Kabul: How I negotiated with Taliban to make it to the safety of Indian embassy

A royal drama in my backyard

The assignment that took me to Jaipur was the settlement of the long-standing Rs 15,000 crore property dispute involving the descendants of the erstwhile royal family. You can read the story here.

While many members and friends of the the erstwhile royal family of Jaipur spoke to me on condition of anonymity, the only one who agreed for an interview was Maharaj Devraj Singh, the grandson of the late Rajmata Gayatri Devi.

When I went to meet Devraj, he was kind enough to show me around the hall of what was once the residence of Gayatri Devi, Lily Pool, full of artefacts and priceless photographs of the royals.

As I spoke to the scions of the erstwhile royal family and researched for my story, it hit me that there was enough drama here for a desi Crown series.

From brothers betraying brothers, to fighting for the favour of the Rajmata, the pressure on the royals to behave and talk in a certain way — royals, who I had imagined to be leading ordinary (only more rich) lives — it was an eye-opener, as few in India really have the kind of fixation on royal families as often witnessed in many other countries.

Meeting Amra Ram

From Jaipur, we moved towards Barmer, and into remote, interior villages of Rajasthan, exploring stories of corruption and talking to RTI activists fighting it.

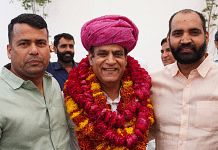

Our first stop after meeting Amra Ram — the RTI activist who was allegedly beaten up in Barmer for his activism — at a hospital in Jodhpur, was Jassodon Ki Beri, his village.

His wife, son and daughter were waiting for us when we reached. “Hum BPL log hain madam, aapko baithne ke liye sofa bhi nahi de sakte (we are poor people, can’t even offer you a sofa to sit),” his wife said apologetically, sitting outside one of the nearly-bare rooms of their part-pucca house.

This village didn’t have a motorable road. The mobile and internet network hardly worked either.

Cattle rearing is the main source of livelihood for people here, the groundwater is too saline to allow agriculture. With no irrigation systems in place, the only crop grown here is bajra (millets) and the harvest is just enough for families to sustain themselves, said local residents.

Electricity connections were installed not more than five years ago, added the villagers, and even now there are long power cuts, with electricity being available for only four-five hours in a day. Even then, when they use rented desert coolers in the summer, the electricity bills are often as much as Rs 10,000 a month, some of the local residents alleged.

The hardship faced by these people, the daily struggle for survival, made Amra Ram’s determination to rise above it and stand up for justice and the rights of those around him, even more heartening — humbling for one like myself, used to the privilege of being “heard”.

There are many more like Ram, across villages in Rajasthan and India, braving threats, attacks and difficult lives, to stand up for the cause of common rights, but rarely do their stories go beyond their neighbourhoods, in an age where the size of one’s social media following decides his or her success or reach. Read the story here.

Camels in the wild

If your imagination of a Rajasthan village includes people riding camels, think again. The use of the animal for transportation has significantly reduced in recent years, with more and more people depending on cars, buses or two-wheelers for mobility and tractors for farming.

Bhagwan Singh, an RTI activist in Barmer, told me he once had five camels, but released them all. “I sometimes bring them back during the monsoon, go in the jungle to catch them, but I don’t really need them anymore. A lot of people have released their camels so you’ll find a lot of wild ones on your way,” he said.

Rajasthan passed the Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act in 2015, which banned export of camels out of the state for slaughtering.

As a result, the demand and valuation of the animals have come down and families that would earlier breed camels now don’t want to keep them any more. According to a Down to Earth report, the animal is now in greater danger than before, and the camel population in the state has come down.

You may run into them in the deserts now, as they forage for food. But keep a safe distance if you want to photograph them. If angered, they can attack. Trust me, one did come charging at me.

(Edited by Poulomi Banerjee)

Also read: Police scrutiny, poor roads & mud-caked sandals — A reporter’s diary from Tripura & Manipur

COMMENTS