Kuruvilangad (Kottayam): “I realised I can’t hide anymore,” Sister Ranit MJ said quietly, her voice giving away the slightest hint of a tremble.

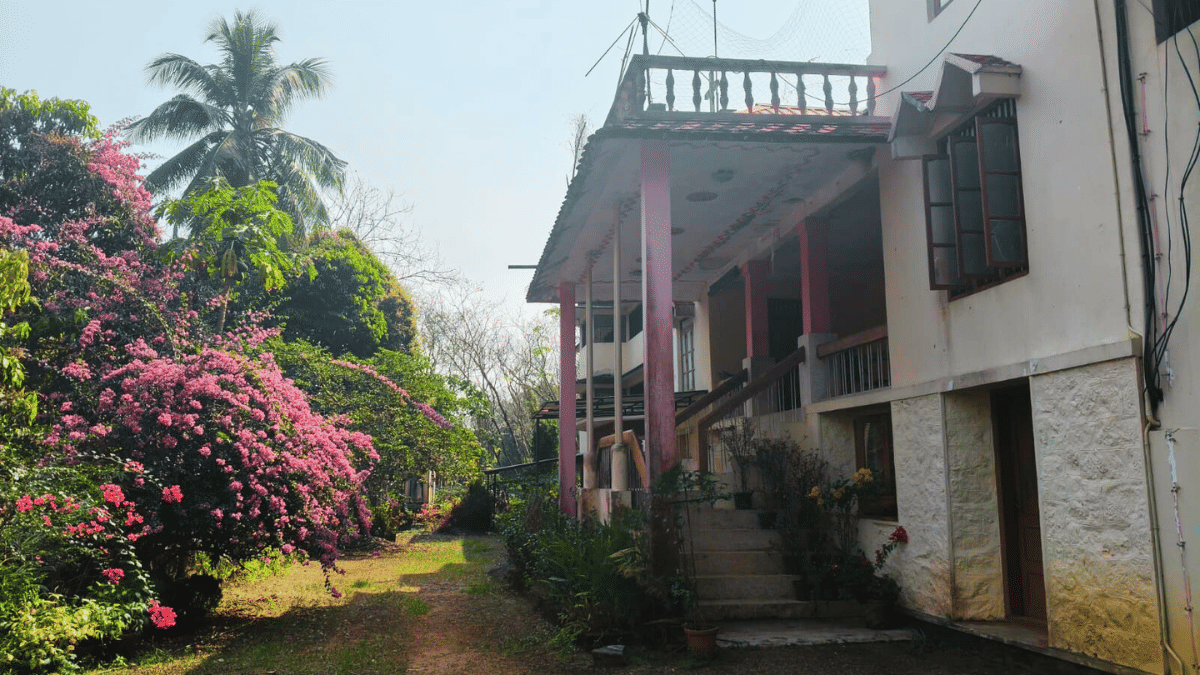

Sitting in the living room of St Francis Mission Home in Kuravilangad, a small town in Kottayam district of Kerala, the nun who was at the centre of a sexual assault case against Bishop Franco Mulakkal decided it was time to step forward.

So, over three years after a Kottayam court acquitted Mulakkal of all charges, Sister Ranit disclosed her identity to the media and spoke up publicly.

The case, which led to a historic protest by nuns and shook the Catholic Church in Kerala, has left Sister Ranit and two fellow nuns living without institutional support. They make ends meet by tailoring, embroidery, small-scale poultry farming and agriculture.

The 50-year-old nun said her family and well-wishers had been asking her to speak up for a while, but she found the courage only after watching another survivor speak out despite being denied justice.

“It was the judgment in the actor assault case. I felt she didn’t get justice. Her case was reported within hours (of the alleged assault)… Many had blamed me for filing mine (the police complaint against Mulakkal) much later. When I saw that case, I realised I couldn’t stay silent. My sisters were my face and limbs (my voice and strength). Now. I have to come out myself,” she told ThePrint.

The nun was referring to the 2017 case in which an actor had accused a colleague, among others, of abduction and sexual assault. Last month, Malayalam star Dileep—who was alleged to be the mastermind in this case—was acquitted.

Also Read: Why nuns’ arrest in Chhattisgarh has put Kerala BJP in a bind

Case that shook the Church

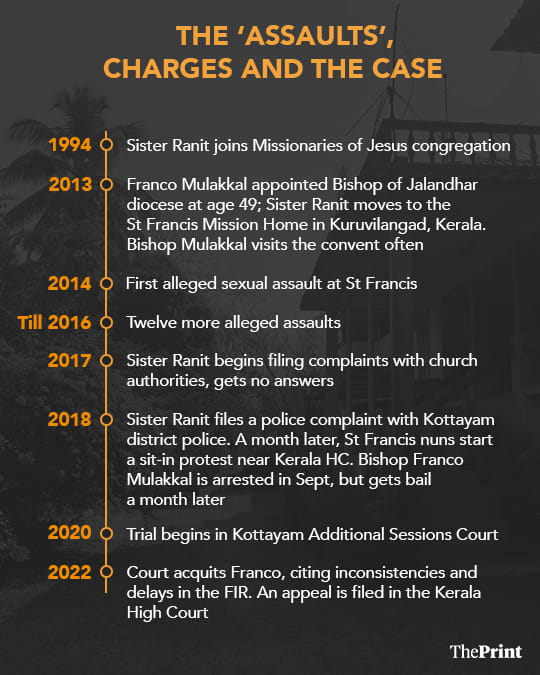

Sister Ranit filed a complaint of repeated sexual assaults by Mulakkal with Kottayam police in June 2018, leading to his arrest in September that year. It was the first arrest of a Catholic priest in India in a sexual assault case.

Mulakkal, hailing from Thrissur district of Kerala, was then the Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jalandhar. He was accused of sexually assaulting Sister Ranit on 5 May 2014, and then 12 more times between 6 May 2014 and 23 September 2016 at a guest room in St Francis Mission Home, where he regularly stayed during visits.

The arrest came after a sit-in protest by several nuns near the Kerala High Court in Ernakulam—also a first in the history of the Catholic Church in the state. The agitation, which began a month after the complaint was filed, was led by five fellow nuns from St Francis Mission Home. But, for Sister Ranit, filing a police complaint was the last resort.

She said she sent multiple letters to church authorities beginning in 2017—to the Mother General (highest ranking authority in a religious order), the Pala Bishop (supreme authority of eparchy of Pala), Cardinal Mar George Alencherry (Major Archbishop of the Syro-Malabar Church) and finally to the Apostolic Nuncio (the Pope’s representative in India).

All went unanswered.

“Mother General asked how I could take action against the supreme authority. Then I told the Pala Bishop. He asked for a written complaint. Later, we met Cardinal Alencherry and then wrote to the Apostolic Nuncio,” Sister Ranit said.

The protests and the complaint gained national and international attention, coming more than a decade after a Boston Globe investigation exposed widespread sexual abuse by priests and cover-ups by the Church.

Sister Ranit told ThePrint that her case was not unique. “It’s not a new thing inside the diocese. There have been many such cases. If it were a local priest or a gardener, they would have taken action much earlier. I didn’t get justice because he was a superior authority.”

The allegations

Born and raised in Ernakulam’s Perumbavoor, Sister Ranit said her calling came early in life.

“Since the fourth standard, I would wear towels like veils. Even then, my family would say I was going to be a nun,” she recalled.

Sister Ranit joined the Missionaries of Jesus congregation in Jalandhar in 1994 with the help of her cousin who was working there. She became a professed nun and Mother General of a pious union in 2004, working mostly in Punjab before moving to Kuruvilangad in 2013. Pious union refers to an association of Catholics approved by a Bishop to perform works of charity, often the preliminary stage before it becomes a religious order.

Court documents say the alleged assaults took place when Sister Ranit was Mother Superior of St Francis Mission, a convent belonging to the Missionaries of Jesus. Franco Mulakkal, appointed Bishop of the Jalandhar diocese in 2013 at age 49—making him one of the youngest to hold the position in India—regularly stayed there.

According to the prosecution, on 5 May 2014, after reaching the convent, Bishop Mulakkal asked Sister Ranit to iron his cassock and bring some documents. When she knocked on his door around 10.45 am, he opened it but locked it from inside as she entered.

He then sexually assaulted her and threatened to “eliminate” her if she told anyone, the prosecution alleged.

The nun said in her complaint that she was raped a dozen more times over the next two years at the St Francis Home.

Reached for comment, Franco Mulakkal told ThePrint that he would convey his case to the court directly.

“My struggle is against evil. I took this stance to get justice. Whatever I have to endure for that, I will tolerate. It’s an unending fight against the forces of injustice. I am not tired of it, I will fight till the end, whoever is against me.”

ThePrint also reached a lawyer associated with senior advocate B Raman Pillai and his firm, which represents Mulakkal. This report will be updated if and when a response is received.

Retaliation & revenge

Sister Ranit said that once Mulakkal realised she was alerting the church authorities about the assaults, he started taking “revenge”. She said he appointed a Mother Superior above her to monitor her at the convent, locked her basic supplies in an almirah, and she started receiving calls from Jalandhar accusing her of attacking the Mother Superior.

Ranit said Mulakkal filed a police complaint in Punjab, accusing her brother of threatening him. The same complaint was later filed with Kottayam police, which summoned him for questioning.

Fed up, Sister Ranit told her brother to show the handwritten letter she’d earlier written to Church authorities, informing them about the sexual assault. Police closed the case against her brother in a year’s time, and asked the nun to file an official complaint on the sexual assault, she said.

Taking police on their advice, Sister Ranit in June 2018 and submitted her complaint.

Mulakkal was booked under sections 342 (wrongful confinement), 376(2)(k) (rape by a person in dominance), 376(2)(n) (repeated rape), 376C(a) (sexual intercourse by a person in authority), 377 (unnatural offences), and 506(II) (aggravated criminal intimidation) of the erstwhile Indian Penal Code (IPC).

“We wouldn’t have come out if he hadn’t done those vengeful acts. Our only demand to the diocese was to shift us under another Bishop. But they were teaching us discipline,” she said.

Mulakkal, arrested in September that year, was granted bail a month later. The trial began in September 2020 in the Kottayam Additional Sessions Court, relying on 120 documents and 39 witnesses, with Sister Ranit testifying as the main witness.

The Jalandhar diocese did not respond to requests via phone for comment.

Acquittal & appeal

The verdict, in January 2022, acquitted Franco Mulakkal, citing the prosecution’s failure to prove charges beyond reasonable doubt, delays in filing of the FIR, inconsistencies in the Sister’s statement and procedural lapses. It also noted that her earlier complaints to church authorities did not allege rape or sexual assault. “PW1 (prosecution witness 1) cannot be regarded as a sterling witness. She had given inconsistent and mutually contradictory versions before various authorities,” the court said, clearing Mulakkal’s name.

An appeal against the lower court verdict was filed in the Kerala High Court in March 2022, and in June 2023, the Vatican announced it had accepted Mulakkal’s resignation.

A long way to justice

After Sister Ranit disclosed her identity publicly to a Malayalam news channel on 10 January and spoke of hardship since losing the congregation’s backing, the Kerala government sent them a ration card.

Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan last week announced that the state will appoint advocate B.G. Harindranath as public prosecutor in the case. Two months ago, Sister Ranit had met Vijayan and appealed for help.

“We haven’t met the lawyer yet. But we are planning to get an appointment. It took some time to get a public prosecutor,” Sister Ranit said.

Harindranath did not respond to request for a comment via text message.

Life since the case

A blue board now marks the entry to St Francis Home, which sits along a narrow road through fields of tapioca and nutmeg trees, not too far from the Ernakulam district border. Once a convent, old-age home and hostel, the space between ‘St Francis Mission Home’ and ‘Kuruvilangad’ belies its lost title, stripped of its status by the diocese after the case.

The convent, Sister Ranit said, was divided after she filed the complaint in 2018. One faction supported Mulakkal and the other backed her. While the trial was going on, the diocese appointed 12 nuns to monitor her and her supporters, she alleged.

“They monitored who came and went, even noting car numbers. They wanted to make sure we felt stressed and never relaxed,” Sister Ranit said.

After the 2022 verdict, the diocese sent transfer orders for the six nuns, including Sister Ranit, to different convents in Punjab, Bihar and Kannur (Kerala). When they refused, it stripped St Francis of its convent designation.

“But we said the case is not over yet. High Court proceedings were ongoing. Then, we received letters saying we should take a ‘leave of absence’. We refused. It’s something we should choose, not be forced upon. So, they closed the convent to oust us.”

The nuns stopped receiving allowances for food, medicine and other expenses.

“I didn’t get justice… This is my 32nd year in this congregation. I only stayed in my home for 17 years,” Sister Ranit said.

Eight years after the protest, three of the six nuns who led it—Sisters Ranit, Alphy MJ and Ancitta MJ—are still living at St Francis Home. Three others left the home and nunhood over the years because the stress was too much to handle, Sister Ranit said.

“They were young, not like me. Here, we were not allowed to do anything. I had limitations to protect them. I believe that it was good that they left. Otherwise, I would have still not come out (right now),” Sister Ranit said.

The sisters supported each other through group Bible readings and by learning embroidery. Some returned to education and completed their Master’s degree in social work.

The remaining nuns start their day with a morning prayer and use only the room, kitchen and needed space in sprawling St Francis Home. They get aid from well-wishers, and make money through embroidery and farming.

Though the nuns say they did not get justice from the religious congregation that they dedicated their lives to, they are still holding on to their belief and faith in the judiciary.

“I joined this (nunhood) with passion. It’s difficult to leave when things get tough. It’s something I have lived and grown in over the years. I hope something will change. I can’t transform the system completely; it’s a big structure. But maybe, something might change slowly, and future generations might benefit a little,” she said.

(Edited by Prerna Madan)