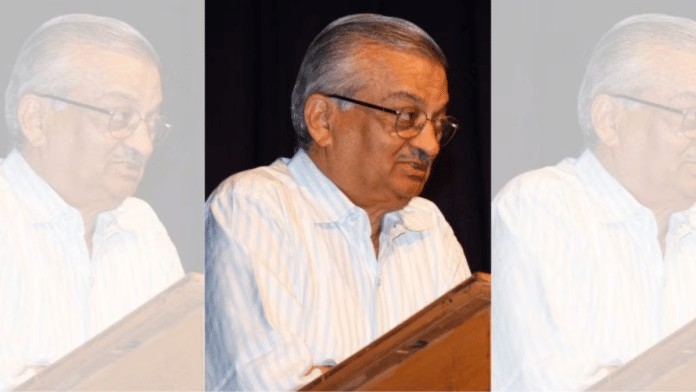

New Delhi: With the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act, 2025 in place, the government now needs to come up with some kind of policy facilitation, like providing soft loans, to make nuclear power even more competitive, former Atomic Energy Commission chairman Dr Anil Kakodkar has told ThePrint in an interview.

Kakodkar, one of India’s top nuclear scientists, suggested scaling up Research & Development and focusing on creating a startup ecosystem for the nuclear power sector.

“The SHANTI Act is fine, but we need to move to the next level simultaneously to realise success…. Nuclear power projects have a long gestation period; the interest (on loans) during construction is a big burden. Now, if the government could create some framework as it has done for the renewable energy sector, then, I think it will make nuclear power become even more competitive than it is today,” he said.

Kakodkar said that producing 100 gigawatts of nuclear energy by 2047 may seem like a large target. “But in terms of India’s requirement as a developed country, I think it may still be one-tenth of what India would require going forward. So we have miles to go.”

Besides scaling up Research and Development in the nuclear sector, Kakodkar also emphasised there should be a thrust on innovation, and it has to be “very fast, particularly when you are talking about new designs, first-of-kind designs, etc”.

“So, we need to create that culture both within the government, but more importantly, outside the government in the universities and in the industry,” he said.

A start-up culture will also give an impetus to the sector, Kakodkar feels. “….in a nuclear plant, there is system-level work, system engineering. This can be done by big players, but then there are a lot of small things that are required, and that can come through the startup movement very effectively.”

Also Read: Thorium utilisation is where India’s nuclear renaissance truly begins: Anil Kakodkar

Nuclear suppliers’ liability

Kakodkar said the supplier liability provision in the 2010 Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (CLND) Act allowed the operator to hold the supplier liable in the event of a nuclear incident resulting in damage, which had become a major “sticking point” for foreign companies considering coming to India.

“We had planned to set up some capacity through imports…. but in reality, nothing moved,” he said, citing the example of Jaitapur in Maharashtra and Kovadda in Andhra Pradesh, the two sites where the government had announced setting up nuclear reactors way back in 2010.

While in Jaitapur, the government had announced plans to set up nuclear power reactors in cooperation with French company Electricite de France (EDF), in Kovadda, it had proposed setting up nuclear power reactors in collaboration with US-based Westinghouse Electric Company. However, neither of the two projects has taken off.

“The supplier liability clause has been a contentious issue. So, I think that the new formulation actually addresses that issue. And it is more in line with the framework, which is practised more generally in the international community,” Kakodkar said.

The SHANTI law alters the CLND Act’s section 17, which dealt with suppliers’ liability. The SHANTI law removes Clause B of the section, which had provided operators with a right of recourse against suppliers if a nuclear incident occurred due to an act of the supplier or its employee.

This included cases involving the supply of equipment or materials with patent or latent defects, or the provision of sub-standard services.

But the non-inclusion of this provision in the SHANTI law has invited widespread criticism from opposition parties.

The new law instead states that the operator’s right of recourse will now be based on what is specified in the contract signed between the two parties.

Kakodkar said the compensation framework under the new law is layered. “There is a liability of the operator, which is absolute. Operators can take recourse to the supplier. But should there be a requirement for compensation of an amount bigger than what is provided for in the law, then there are provisions where one could draw some money through international cooperation. India is part of the broader, international regime on this.”

“Should there be a need beyond some minimum threshold, so that is available. And should there be even bigger than that, I think, it’s the sovereign, which could also chip in later. So the provision is layered, and the question is how much is commitment the operator has been asked to kind of make that upfront,” he said.

The SHANTI law puts the maximum liability of the operator at Rs 3000 crore. However, if the liability is more than that, there is a provision of 300 million Special Drawing Rights (SDR) or a higher amount that the Centre may specify by a notification.

SDR is an international reserve asset created by the International Monetary Fund, the value of which is determined and allocated by it to member countries. Currently, the value of 1 SDR is about Rs 130.

The Centre may take additional measures, including seeking funds under the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage signed at Vienna, if the compensation to be awarded under this act exceeds 300 million SDR. India is a signatory to the convention.

“….It’s a balanced approach, which is very important. On one side, it should protect people, but on the other side, it should not become completely unmanageable for the utility industry or the supplier industry. So I think it’s a good balance between these aspects,” Kakodkar said.

Kakodkar also stressed that while bringing in private investment in the sector, one has to make sure safety is the topmost priority.

“The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, which has been given a statutory backing in the new law, is a very robust and mature organisation.”

Thorium push

Kakodkar also emphasised the need to move from Uranium, which is the primary fuel in India’s nuclear reactors today, to Thorium for the country’s long-term energy security.

“I think the Uranium market is going to be more and more difficult as we go along because the demand for Uranium is expected to grow, and if the share of Indian demand becomes a larger fraction of this total global production, then we’ll have challenges in terms of accessing Uranium and that too at the right price,” he said.

Kakodkar added that India’s objective has always been to move towards Thorium because “we have plenty of reserves”.

“We can meet the energy requirements of India, plus also export energy along with our reactors to other countries,” he said, adding that it is important from the point of view of long-term energy security.

(Edited by Ajeet Tiwari)

Also Read: More power, less blame: SHANTI Bill’s ‘pragmatic’ take on prickly issue of nuclear liability