New Delhi: Kerala’s Wayanad is currently reeling from the effects of the devastating landslides that have claimed more than 400 lives so far, but this is not the first or the worst disaster to strike the region. Exactly a 100 years ago in 1924, Kerala witnessed one of the worst floods in history, known as the Great Flood or Great Deluge, with Wayanad occupying centre stage.

Since it was the year 1099 according to the Malayalam calendar, this is popularly called the Great Flood of ‘99.

Records from the India Meteorological Department show that many parts of what is now the state of Kerala received more than 3000 mm of rainfall during the southwest monsoon of 1924 — one of the highest ever in the state, along with the 1961 and 2018 floods. Analyses of the 1924 floods explain how, due to the heavy rainfall, most of the rivers of the state, such as the Chaliyar, Periyar, Bharathapuzha and Kallayi, flooded and battered entire villages, houses and crops.

More specifically, a Central Water Commission report shows that a majority of the rain occurred between 16 and 18 July of that year, with rainstorms in the Devikulam and Munnar hill stations in modern-day Idukki district. In just three days, Munnar received 897 mm of rainfall that year, while Devikulam recorded 751 mm in just two days. For context, the landslides in Wayanad on 29 and 30 July were triggered by less than 300 mm of rain.

Data from the IMD’s archives accessed by ThePrint show that in July 1924, Wayanad had the highest rainfall out of all 14 modern-day districts in the state, at 3,193.6 mm. The normal rainfall for that month was 899 mm, indicating an almost 250 percent departure in Wayanad.

Other districts like Palakkad, Malapuram and Kozhikode also saw high rainfall of between 1,400 and 1,800 mm during the month, but Wayanad was at the top.

Due to a lack of official data, there’s no log of the total casualties or damages that resulted from the 1924 floods in Kerala. However, academics, historians and scientists have tried to piece together exactly what happened and which areas were affected by the rain and resultant floods, using existing sources of the Travancore government and colonial records.

Devastation & mentions in popular history

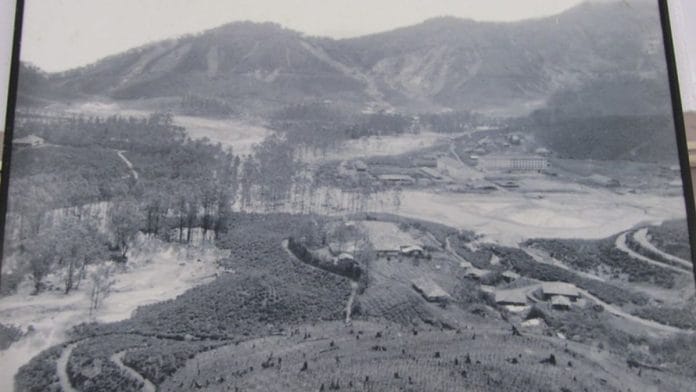

According to Janamaithri, a journal run by the Kerala government, many modern-day districts, including Kochi, Thrissur, Ernakulam, Idukki and Kottayam, were entirely inundated in that period, not just because of the rains, but also the flooded rivers. The document also said that the Kundala Valley Railway — the first monorail in India — was washed away by the floods. Janamaithri and other reports about the incident also mention that the Karinthiri Mala mountain was washed away, and with it the Ernakulam-Munnar road.

Historians such as Manu S. Pillai have used texts, like the Report of the Mannar Flood Relief Deputation, the Report of the Land Revenue and Income Tax Commissioner, and press notes from the chief secretary’s office from the year 1924, to reconstruct the events of that period and the relief efforts that ensued.

Pillai’s book, The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore, talks about how after the floods, parts of Travancore were “turned into a massive swamp and even portions of the high ranges were submerged”. Corpses were said to be floating around in the water, and Pillai’s book and Janamaithri both say that in some places, the water reached 20 feet in height.

One village near Travancore reported that 6,40,000 kg of grain, 1,000 acres of land and 500 houses were destroyed by the deluge, according to the Kerala State Archives accessed by Pillai. His book explains that there were hundreds of such villages, and how both the Travancore regime and the British colonial government tried to ensure a good harvest for the next season through agriculture loans, free timber to construct houses and tax waivers.

Other non-fictional accounts of the floods were also constructed by scholars, such as P. Priya in her paper titled ‘When the Rains Lashed Malabar: A Case Study of Flood Havoc of 1924’, in the Proceedings of the Indian History Congress (Vol. 79 (2018-19)). The paper provided context about how the structure and geology of rivers in the state — most of which flowed west — contributed to their flooding during the 1924 rains.

The location of the Western Ghats also played a role in many regions, like Calicut being entirely isolated from the rest of Kerala once the Kallayi river flooded. Priya, too, cites texts such as the Madras Revenue Department records of 1924 to say that in just four districts, more than 30,000 acres of paddy fields were submerged by the floods.

Like in 2024, 100 years ago too, the rains had a cascading effect in terms of landslides in the state, and in the very same regions. It is Priya’s text that mentions how the rainfall and floods during 1924 led to landslides, especially in Wayanad, Chirakkal, Eranad and Valluvanad. She writes about how these blocked roads and washed away bridges, with the blockage of Ghat roads leaving Wayanad “completely isolated during the floods”.

As Pillai’s book states, though, the effects of the flood of ‘99 remained far longer in the “form of local lore and family memory”, with many old people in Kerala using the event as a marker of time.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Wayanad landslides: Centre blames Kerala for allowing ‘illegal mining, unregulated human habitation’