Hisar: Did you know that paan serves more than just a mouth freshener? Or that the biryani’s Mughal origin may be exaggerated or even a myth? Many such interesting culinary insights were shared by academician and food critic Professor Pushpesh Pant at a session during the Jindal Literature Festival.

Referring to all regional foods as “Indian cuisine” blurs the country’s incredible diversity, said Pant, adding that food in India is layered in different traditions, geography, history, caste, communities and migration.

In ancient India, people even judged a king’s popularity by the food in his kitchen. But Pant challenged the whole idea of what is referred to as “Indian food”.

The real flavours of Rampur’s kitchens have long been overshadowed by the more famous Awadhi Rasoi, he said.

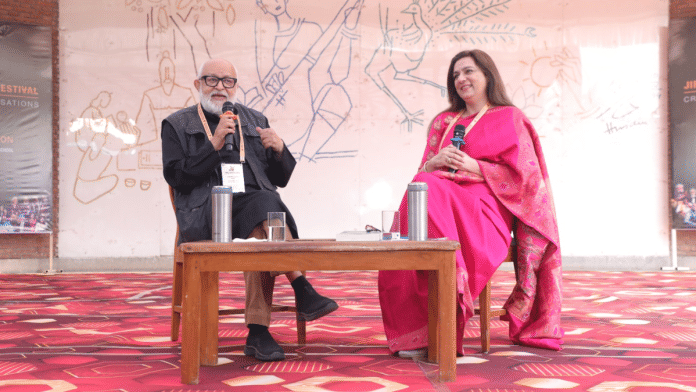

“Biryani is just a heightened version of pulao. The common belief that biryani came from the Mughals is exaggerated or even a myth. Multiple variants of biryani were mythologised to seem more exotic or aspirational, especially among the nouveau riche,” Pant said Friday at the panel discussion with writer Tarana Husain Khan on the topic ‘The Royal Kitchen’.

The biryani, whose one version hails from Awadh region (in present day Uttar Pradesh), was the most ordered dish in India, according to Swiggy’s 2024 report.

Pant briefly touched on the dietary habits of the British during their reign in India. “The British fear of Indian spices, their obsession with hygiene and blandness, and the constant anxiety to ‘Europeanise’ Indian ingredients gave birth to an artificial hybrid cuisine known as ‘Sahab ka khana’ — literally, ‘the food of the masters’,” he said.

Khansamas of Rampur

Rampur cuisine has historically been a proud contender for the best food in India, but it is mostly limited to food connoisseurs. During the British rule, the Rampuri nawabs sided with the British. This became the leading reason for the survival of their unique cuisine.

“The recipes of Rampuri cuisine are not just about taste but about memory and tradition. They were passed down orally from one ‘khansama’ (cook) to another — a practice called ‘seena dar seena’. Because of this fragile chain, many dishes like shabdeg, a meat-and-turnip stew, were lost over time but are now being revived,” Pant said.

“Compared to Awadhi cooking, Rampuri cuisine was considered simpler because its royalty were Pathans. They preferred restraint and avoided adding too many Indian aromatics like kewra, rose water, ittar or heavy masalas. That’s why I see Rampuri food as a distinct strand in India’s larger tapestry of regional cuisines — it has its own identity, history and value,” he added.

Rules of eating paan

Pant has one of the most exclusive takes on Paan. For him, paan has been a symbol of courtesy, memory and quiet ritual. But like many old traditions, its elegance has dimmed over the years, replaced by novelty flavours and hurried chewing that disconnect it from its cultural roots.

He said, almost feebly, that the reputation of paan was first dented by the rise of the Banarasi paan.

“For me, paan is not about gimmicks but about authenticity. A good paan begins with a fine leaf—Magahi, if you can find it—just a touch of kattha (extract of acacia), a smear of chuna (lime), a sliver of supari (betel nut) and a hint of cardamom. That’s it. No chocolate, no strawberry, no theatrics,” Pant said.

“Today, that ritual has almost vanished. What remains is a reminder that paan, like all our food traditions, needs respect—not reinvention for its own sake,” the academician asserted.

ThePrint is the official media partner for the Jindal Literature Festival.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Women of suspense: The female crime writers reimagining power and vulnerability