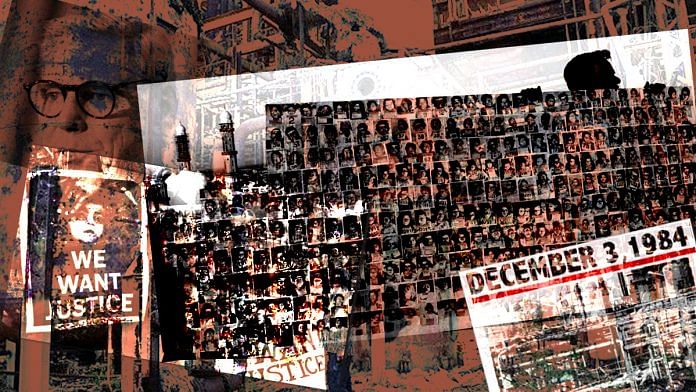

New Delhi: Over 36 years after India saw its worst industrial disaster, the Bhopal gas tragedy, a five-judge Constitution bench is set to start hearings in a curative petition filed by the Government of India.

In 1984, the gas leak at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal killed nearly 4,000, leaving generations thereafter reeling under the harmful effects of the methyl isocyanate gas.

In close to 20 years of litigation, the case has seen a lot of twists and turns. The hearings come nine years after the Indian government filed the curative plea seeking additional compensation from Union Carbide Corporation (UCC), which ran the Bhopal gas plant.

The Supreme Court was to start hearings on 11 February. However, the matter was not scheduled in the top court’s cause list Tuesday.

In this comprehensive timeline, ThePrint details the entire case from when it started to how it played out, especially the rollout of compensation for the victims.

The establishment

1969: Union Carbide India Ltd’s (UCIL) plant in Bhopal was designed by its holding US company Union Carbide Corporation, which held 50.9 per cent of UCIL’s equity. It was built as a formulation factory for UCC’s Sevin brand of pesticides, produced by reacting methyl isocyanate (MIC) and alpha naphthol. Sevin kills pests by paralysing their nervous systems. At the time, MIC was imported from the US in steel containers.

The plant set up on land taken on a long-term lease from the state of Madhya Pradesh.

1975: UCC decided to “integrate backwards” and manufacture ingredients of Sevin at the UCIL’s Bhopal plant. The move came even though the then zonal regulations prohibited locating polluting activity in the vicinity of 2 km from the railway station — where the plant was situated.

Also read: Bhopal gas leak: Supreme Court can now undo collusion between Union Carbide, Indian govt

The leak

2 December 1984: On the fateful night, at 8.30 pm, the Bhopal plant workers under instructions from their supervisors began a water-washing exercise to clear pipes choked with solid wastes. The water entered the MIC tank past leaking valves and set off an exothermic ‘runaway reaction’ causing the concrete casing of tank number 610 to split and the contents leaking into the air.

3 December 1984: Because the residents were given no warning about precautions, many of them ran on to the streets as the leak spread, and met a certain death.

A suo-motu FIR was then recorded by the SHO at Hanumanganj police station against UCC, UCIL and its executives and employees under Section 304 (A) (death by negligence) of the Indian Penal Code. The record indicated:

3828 died on the day of the disaster (the unofficial toll is feared to be much higher — by 2003 over 15,000 death claims have been processed). Over 30,000 injured on the fateful day (a figure that now stands at 5.5 lakhs). 2544 animals killed.

The litigation: India and US

3 December 1984: Five junior employees of UCIL were arrested.

6 December 1984: The case was handed over to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The government of Madhya Pradesh set up a commission of inquiry, called the Bhopal Poisonous Gas Leakage Inquiry Commission, presided over by N.K. Singh, a sitting judge of the Madhya Pradesh High Court.

7 December 1984: Union Carbide chairman Warren Anderson, and senior level management officials Keshub Mahindra and V.P. Gokhale, were arrested and released on bail on the same day. Anderson was escorted out to Delhi on chief minister Arjun Singh’s special plane.

Nearly 145 claims were filed on behalf of the victims in various US courts. These were consolidated and placed before the Southern District Court, New York presided over by Judge John Keenan.

29 March 1985: The Parliament enacted the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster (Processing of Claims) Act 1985 whereby Union of India would be the sole plaintiff in a suit against the UCC and other defendants for compensation arising out of the disaster.

8 April 1985: The Union of India filed a complaint on behalf of all victims in Keenan’s court in the US.

15 December 1985: The N.K. Singh commission wound up on 15 December 1985. After a week, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research submitted a detailed report squarely implicating the Union Carbide for faulty design of the plant as well as its reckless disregard of operational safety.

Also read: Abdul Jabbar, Bhopal gas tragedy’s oldest activist, turned ailing survivors into warriors

12 May 1986: Judge Keenan dismissed the Union of India’s claims conditional upon UCC submitting to the jurisdiction of Indian courts.

In 1986, two writ petitions were also filed in the Supreme Court of India challenging the validity of the Claims Act.

5 September 1986: The Union of India filed a suit against UCC in the Bhopal district court.

4 January 1987: The 145 individual plaintiffs and the UCC filed appeals against Judge Keenan’s order dated 12 May 1986. On 4 January 1987, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit disposed of the appeals by modifying the conditions subject to which the suit by Union of India had been dismissed.

5 October 1987: The Union of India’s further petition for a writ of certiorari against the order of the Court of Appeals was declined by the US Supreme Court.

1 December 1987: The CBI filed a charge-sheet in the court of the chief judicial magistrate, Bhopal, charging the accused for offences under Section 304 Part II (culpable homicide) of the IPC and other offences.

17 December 1987: An interim compensation of Rs 350 crore was ordered by Bhopal district judge M.W. Deo.

4 April 1988: This compensation was challenged before the Madhya Pradesh High Court. By a judgment dated 4 April 1988, the HC reduced the interim compensation to Rs 250 crore. The UCC challenged this further before the Supreme Court.

14-15 February 1989: On the UCC appeal, the Supreme Court approved a settlement whereby UCC and UCIL would pay $470 million to the Union of India in a full and final settlement of all claims, and criminal proceedings would stand quashed.

4 May 1989: Following widespread protests over the manner of arriving at the settlement and quashing criminal proceedings, the Supreme Court agreed to review the settlement.

22 December 1989: The court upheld the validity of the Claims Act applying the doctrine of parens patriae [Charan Lal Sahu v. Union of India (1990) 1 SCC 613]. Under this, an authority acts as a legal protector of citizens’ rights when they are unable to assert those rights themselves.

1990: Looking at the environmental factors in Bhopal, the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) submitted its first report in 1990 stating that there was no contamination of the groundwater in and around the plant site. Subsequent documentation revealed that UCC itself doubted NEERI’s conclusions since their internal notes revealed that majority of liquid samples collected from the area “contained naphthol or sevin in quantities far more than permitted by ISI for inland disposal”.

Also read: 33 years on, India unable to clean toxic waste from world’s worst industrial disaster

3 October 1991: The Supreme Court declined to reopen the settlement justifying it under Article 142 of the Constitution — it allows the court to go beyond the plea and do “complete justice”. However, the criminal proceedings were directed to be revived. The court expressed hope that UCC would contribute Rs 50 crore to setting up a hospital at Bhopal for the victims.

1 February 1992: The Bhopal CJM declared Warren Anderson, UCC and UCC (Eastern, Hongkong) as proclaimed offenders. The magistrate directed that if the parties do not appear on 27 March 1992, he would order attachment of UCC’s shares in UCIL under Section 82 of Code of Criminal Procedure (warrant for an absconder).

27 March 1992: Warren Anderson and both the UCCs failed to appear before the magistrate. However, attachment of shares was put off at UCIL’s request.

22 June 1992: The trial of the Indian accused was separated and committed to sessions court.

19 August 1992: The central government announced a scheme of interim relief to the gas victims at Rs 200 per month subject to a maximum of 5 lakh victims for a period of three years beginning 1 April 1990.

The Supreme Court, in a writ petition by the Bhopal Gas Peedith Mahila Udyog Sangathan, directed via its orders dated 19 August and 4 November 1992 interim relief to be paid to all victims, including those left out from the scheme as announced.

16 October 1992: By an order dated 24 February 1989, the $470 million Settlement Fund had been directed to be kept in a separate dollar account with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in the name of the Registrar of the Supreme Court.

On an application by the Union of India, the court on 16 October 1992 permitted the account to be now held in the name of the Welfare Commissioner, who was designated to disburse the settlement funds. This was subject to the condition that RBI would not release any part of the amount except on a certificate by the Welfare Commissioner that the amount withdrawn was for payment of compensation to the claimants.

8 April 1993: The Bhopal sessions court framed charges against the Indian accused for offences under Section 304 Part II of the IPC.

28 May 1993: The Supreme Court directed continuation of interim relief to the victims from 1 June 1993 and permitted Union of India to withdraw Rs 120 crore from the Settlement Fund for this purpose.

10 December 1993: British lawyer Ian Percival, who worked for the rights of the Bhopal gas tragedy victims, approached the Union of India with an “offer” to sell the attached shares of UCIL to raise money for the Bhopal Hospital to be built by UCC.

The Union government filed an application in the top court for enforcement of UCC’s obligation to build the expert medical facility. At the first hearing of the application, Percival was present and heard. The court asked the government to consider the Sole Trustee’s — in this case, the Government of India — suggestion which was “eminently reasonable, worthy of consideration”.

14 February 1994: The Supreme Court modified the Bhopal magistrate’s attachment order and permitted the attached shares to be sold.

September 1994: UCC entire stake in UCIL was sold to Indian tea company McLeod Russel Ltd for Rs 170 crore. It later renamed UCIL as Eveready Industries India Ltd, which still operates in the Indian market. After the release of around Rs 125 crore (inclusive of dividends) to the Bhopal Hospital Trust (BHT), the balance sale proceeds to the tune of about Rs 183 crore remained under attachment.

19 September 1995: Krishna Mohan Shukla, a lawyer practising in the Supreme Court, filed a PIL drawing its attention to numerous illegalities in the matter of categorisation, processing and adjudication of claims by the deputy welfare commissioners under the settlement scheme.

It was stated that at lok adalats held under the scheme, many claimants were being compelled to accept a low compensation of Rs 25,000 in full and final settlement of the claim, and further such order could not be appealed.

3 April 1996: The court directed a sum of Rs 187 crore from the attached monies to be further released to BHT for the construction of the hospital.

1 May 1996: In the petition by Shukla, the court by an order dated 1 May 1996 struck down certain circulars issued by the Welfare Commissioner tribunals, under which a deputy welfare commissioner could not revise the category to classify the claimant unless the Welfare Commissioner approved it. It called for details of the cases settled in lok adalats.

13 September 1996: Meanwhile, the Indian accused failed in their challenge to the order framing charges before the Madhya Pradesh HC. Then they approached the Supreme Court by way of Special Leave Petitions. On 13 September, the court diluted the charges against the Indian accused from Section 304 Part II of the IPC to Section 304 A.

7 November 1997: In the Shukla petition, the court made an order permitting a claimant who was aggrieved by an order made in the lok adalat to challenge it by way of an appeal.

September 1998: Madhya Pradesh took control of the plant land, and put up notices in nearby residential areas warning against drinking water.

International environmental NGO Greenpeace came out with an independent report of test of soil and water samples collected in areas around the plant site and confirmed extensive contamination. Sevin was seen to have leaked from the ruptured tank and water supplies were found contaminated with “heavy metals and persistent organic contaminants”.

15 November 1999: In the US, a fresh class action litigation was filed in the court of the Southern District New York by Sajida Bano, Haseena Bi and five other victims directly affected by the contamination, claiming damages under 15 counts. Counts 9 to 15 related to common law environmental claims.

28 August 2000: Judge Keenan dismissed the class action claim on the ground that the 1989 settlement covered all future claims.

5 February 2001: The US Federal Trade Commission approved the merger of UCC with Dow Chemical Company.

15 November 2001: The Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed in part, but remanded claims on counts 9 to 15 to Judge Keenan.

April 2002: In discovery proceedings before Judge Keenan, UCC submitted over 4,000 documents.

March 2003: Judge Keenan dismissed the suit of Hasina Bi again — this time on grounds of limitation.

March 2004: The Court of Appeal affirmed in part but asked Judge Keenan to consider claims of Bi arising out of damage to property and the issue of decontamination by UCC of the site if the Union of India and Madhya Pradesh had no objection.

30 June 2004: After victims went on a hunger strike in Delhi, the Government of India submitted a memo before Judge Keenan stating it has no objection to decontamination being undertaken by UCC at the company’s cost.

19 July 2004: Back in India, in a representative application by 36 victims — Abdul Samad Khan and others — the Supreme Court directed disbursement of balance compensation.

17 September 2004: In another writ petition by the Bhopal groups for medical relief and rehabilitation, the court finalised the terms of reference of two committees — an advisory committee and a monitoring committee — appointed by it.

26 October 2004: In the Abdul Samad Khan application, the court directed the disbursement of balance compensation to commence from 15 November 2004 and conclude by 1 April 2005. The court accepted the action plan prepared by the Welfare Commissioner.

June 2010: All eight accused, including the then chairman of Union Carbide, Keshub Mahindra, were convicted by a court but let off with minor punishment.

August 2010: The CBI filed a curative petition in the top court to recall the order issued by it in September 1996 (SC had diluted charges against Union Carbide’s Indian officials).

May 2011: The court dismissed the CBI’s curative petition for harsher charges against UCIL’s Indian officials.

August 2011: The central government filed another curative petition in the Supreme Court with regard to additional compensation for the victims of the Bhopal gas tragedy. The Centre said UCC, now owned by Dow, should be directed to pay an additional compensation of Rs 7,413 crore.

July 2013: The Bhopal district court asked Dow to explain why UCC repeatedly ignored court summons.

September 2014: Warren Anderson dies. It became known publicly only at the end of October 2014.

February 2020: Curative petition listed before a judge bench for regular hearing.

Also read: The lazy way to remember the Bhopal Gas tragedy