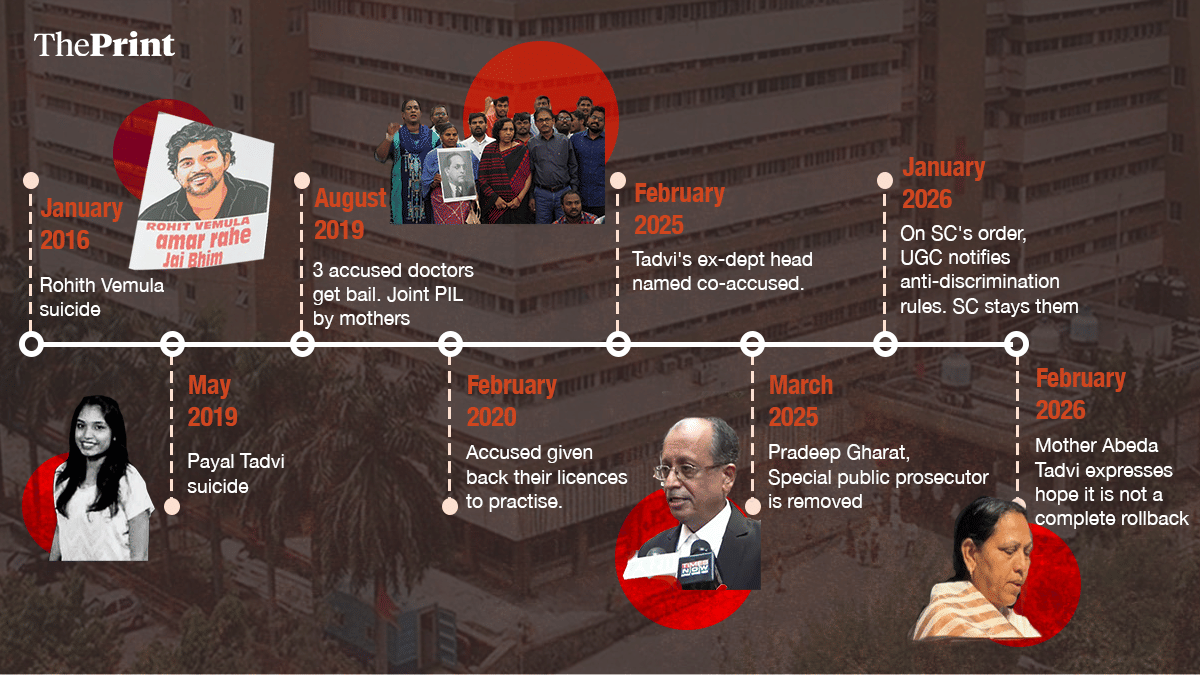

Mumbai: The Supreme Court’s January stay on the University Grants Commission’s (UGC) fresh rules to tackle caste-based discrimination in colleges has once again turned the spotlight on the 2019 suicide of Payal Tadvi. A second-year postgraduate student of gynaecology and obstetrics at Mumbai’s BYL Nair Hospital, she died by suicide in her hostel room, her case eventually leading to the amended rules, which have now been stayed.

Just like University of Hyderabad student Rohith Vemula (26) died by suicide in 2016 following alleged caste discrimination, the 26-year-old Payal, who belonged to the Tadvi Muslim Bhil Scheduled Tribes community, was allegedly a victim of casteism.

Three of her senior colleagues—Bhakti Mehare, Hema Ahuja, and Ankita Khandelwal—were initially arrested on charges of harassment and casteist remarks on Payal.

In July 2019, the Mumbai Police filed the chargesheet against the trio. During the trial proceedings, Bhakti, Hema, and Ankita were granted bail in August 2019, only three months after their arrest. In February 2020, the Bombay High Court ordered their medical licenses—which had been suspended when the case broke— restored.

The case is yet to reach any conclusion, with Payal’s parents, Abeda and Salim Tadvi, awaiting closure more than six years after their daughter’s death.

“Initially, we were told that the case would be fast-tracked, and we would get a judgment in nine months. But, it’s been seven years now, and we are still waiting,” Abeda Tadvi told ThePrint.

In 2019, Abeda, along with Radhika Vemula, the mother of Rohith Vemula, filed a public interest litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court, listing demands to combat caste discrimination on college campuses and to enforce the 2012 UGC regulations in this regard.

After the 2026 rules were updated at the end of the case, students from the ‘general category’ led countrywide protests. There is now a stay on the implementation of the new rules.

Small quarters, big dreams

Payal grew up in Jalgaon in a modest two-bedroom house with her parents and brother Ritesh, who is polio-affected. She left her home for the first time to study MBBS at the Government Medical College in Miraj, roughly 670 kilometres from Jalgaon.

After her graduation, Payal completed a one-year-long internship at Sangli-based PVP Government Hospital. In 2016, she got married to Salman Tadvi on Valentine’s Day. Like her, Salman was a doctor pursuing his MD in anaesthesia at the King Edward Memorial Hospital in Mumbai. He later took a job at the Cooper Hospital in Vile Parle, and after some time, Payal moved to Mumbai for her postgraduate studies. Salman rented an apartment in Mahalaxmi—close to Nair Hospital.

Traditionally an agricultural community, Tadvi Muslim Bhils were largely left on the margins of the education system, with Payal’s aspirations standing out within and outside her community. After Payal died, her grieving parents told the media she was not only the first doctor in the family but, perhaps, the first woman doctor ever from the entire community.

After Payal’s death, her friends from her MBBS days had told ThePrint how she was a warm, happy-go-lucky girl who, like any other quintessential young adult, loved watching ‘Game of Thrones’ and going out with her batchmates.

One of her friends from Miraj college—Dr Romil Kakad—had told ThePrint in 2019 that Payal, whose course at Nair Hospital started on 1 May 2018, had been disturbed for several months before she ended her life.

She had sent him a text message on 30 November 2018, discussing how everyone was stressed that she might commit suicide. Dr Kakad had mentioned Payal telling him about her three seniors, who were targeting her and not allowing her to perform procedures, such as deliveries and episiotomies—a surgical cut at the vagina to aid a difficult delivery—and that they would loudly scold her in front of patients and relatives.

Also Read: AIIMS group likens Payal Tadvi’s death to Rohith Vemula, says casteism ‘more invisible now’

The letter: ‘Bullied & ignored’

Following Payal’s death, all three accused seniors were booked under sections of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act and immediately suspended from the college. Their medical licenses were suspended. In the remand hearing, the accused maintained that they did not make casteist remarks against Tadvi and that all their comments were about Payal allegedly shirking work.

While there was no physical suicide note at the spot, the Mumbai Police had recovered a photo of a handwritten note in Payal’s room, and a forensic report had confirmed it as Payal’s handwriting.

The suicide note, which was addressed to her parents, squarely blamed the three senior women for her condition and that of another fellow student, Snehal Shinde.

In the note, Payal wrote that they would not let her learn anything at Nair Hospital and restricted her to clerical work and that her complaints to the head of the department also did not help.

The 1,203-page chargesheet filed in July 2019 in three volumes carried statements from nearly 180 witnesses. Some of Payal’s colleagues and staff members, whose statements were attached, spoke about how the accused targeted her for being from the Scheduled Tribes community and getting admission in the medical course through the reserved category.

What is of note is that the chargesheet was filed over six years ago, but the charges are yet to be framed.

In August 2019, the Bombay High Court granted bail to the three accused, but under stringent conditions, which have since been relaxed.

“Most of the time since then has gone in hearing different pleas by the accused asking for relaxations in their bail conditions. The main case has been completely sidelined,” Abeda Tadvi told ThePrint.

Also Read: Dr Payal Tadvi was hardworking, loved dancing and was hooked to ‘Game of Thrones’

The only thing that gets them going

In November 2024, Pradeep Gharat, then the special public prosecutor, made an application before the Mumbai sessions court, where the case was being heard, to include Dr Ching Ling Chiang, the former head of gynaecology and obstetrics at Nair Hospital, as an accused.

The court granted the request to add Chiang as an accused in the abetment to suicide case in February 2025.

However, in March 2025, the Maharashtra government abruptly removed Gharat from the position of special public prosecutor, replacing him with another prosecutor.

Unhappy, Abeda approached the Bombay High Court, challenging the state government notification that removed Gharat the same month that Chiang was named as a co-accused. That case is still pending.

Abeda and Salim have been visiting Mumbai to personally appear at the court hearings since 2019.

“Until about six months ago, we used to come two times a month. But our case has been stalled in the Bombay High Court for a year now, and even the sessions court is not giving any dates. So, our lawyer advised us to come only when there is a major development,” Abeda said.

“We have fought for so long already in the hope for justice that we feel we must see this through till the end. That’s the only thing that keeps us going.”

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Payal Tadvi case isn’t the only one. Many upper caste women harass others, overlooking gender

So, instead of making anti-ragging rules stricter, you frame rules to target people on the basis of caste, by labelling entire group of people as “oppressors”. Pathetic!