Heerpora, Shopian: Light flickered on the street, and for a moment, the inhabitants of a sleepy village imagined hearing a storm coming from the mountains to end the murderous heat of the night. Then, they heard Shabnam Aijaz scream. Aijaz Ahmad Sheikh, her husband and the headman of the village of Heerpora in Shopian, had just been executed at point-blank range, seven rounds from an assault rifle tearing apart his body.

Before his death on 18 May this year, Aijaz often received threats from terrorist groups, neighbours say. His killers remain unidentified.

Four months after the killing, the street that passes by the Aijaz family home in the southern Kashmir village is now festooned with Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) buntings and posters.

Later this week, Shopian will participate in the first election to the Jammu and Kashmir legislative assembly since 2014. Polling across 90 seats is taking place in three phases.

The BJP, however, seems to have forgotten Aijaz—the stone-throwing, pro-jihad teenager who emerged as one of the party’s most visible faces in southern Kashmir after the 2016-17 unrest.

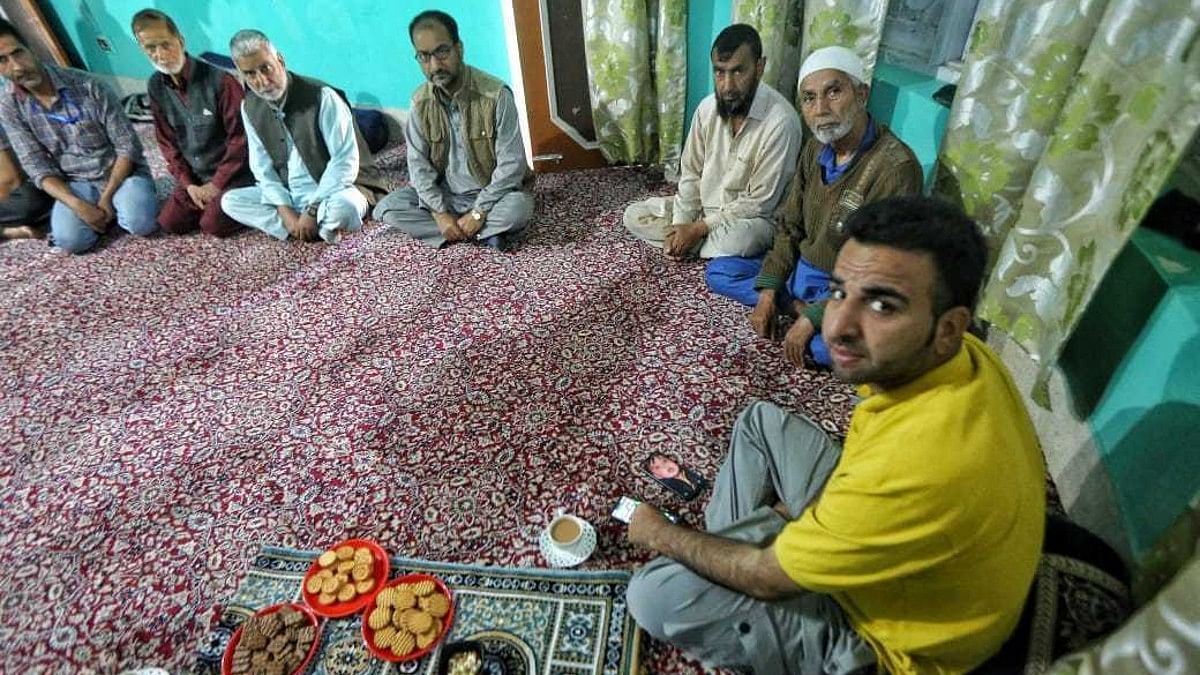

Meanwhile, Aijaz’s family has received neither financial compensation nor a government job for terrorism victims in Jammu and Kashmir. The responsibility of supporting Aijaz’s wife and three children, six-year-old Atif, five-year-old Zaira, and seven-month-old Nur-ul-Ain, has fallen on Aijaz’s brother, Wasim, who has his family, as well, to support.

“I have visited the secretariat in Srinagar three times to push the paperwork for compensation,” Wasim says. “Each time, I get the same answer from officials: ‘Soon’.”

Kashmir’s ‘Generation Rage’, which started its struggle against India in 2008 but lost after 11 years of hitting the streets with stones and bricks, will be the key to the election outcome, many candidates say.

The arc of the story of the stone-throwing protesters such as Aijaz Ahmad Sheikh, along with other less well-known faces, is the key to understanding why ‘Generation Rage’ abandoned leaders calling for turning Kashmir into an Islamic state and what they now hope for in a new political leadership.

Also Read: Ahead of J&K polls, US diplomats visit Srinagar, meet Omar Abdullah & other political leaders

From jihad to jail

‘Little Geelani’ is what his friends teasingly called Zaid, the teenage boy who had earned a reputation for accurately picking out policemen at a 25-metre distance with stones from the rooftops of Shopian’s Malik Mohalla.

His nickname referred to Jama’at-e-Islami patriarch Syed Ali Shah Geelani, who fired the imagination of a new generation of Kashmiri Islamists—Zaid Geelani’s hero.

Aged ten years when he first joined the gaggles of stone-throwing youth who responded to Geelani’s calls for street protests against India, Zaid rose to become one of their leaders.

Election jingles, and speeches broadcast from loudspeakers by the 13 candidates in the fray in Shopian, envelop the bazaar where Zaid now works—sounds of the democratic system he once wanted to dismantle. “I’m going to vote for the first time,” he says, “but my dreams haven’t changed.”

“Like everyone else I knew, I wanted azaadi [independence],” Zaid recalls, revisiting his childhood through the eyes of a just-married 26-year-old struggling on his meagre income as a tailor. “I wasn’t exactly sure what azaadi meant, but I thought it would be a just society, where I would get a decent job, and a good life.”

Later, in 2016, following the killing of jihadist icon Burhan Wani, thousands of young people swelled Zaid’s army. For months after that, the government was left out of large swathes of southern Kashmir. Even armed police, one officer who was serving at the time told ThePrint, were unable to step outside the city police stations for months on end.

Responding, the government came down heavily on pro-jihad leaders.

For four years, Zaid was held at a succession of prisons, including the feared Kot Bhawal jail, which once housed jihadists such as Jaish-e-Muhammad chief Masood Azhar Alvi under Kashmir’s controversial public safety Act.

From prison, Zaid watched Kashmir lose its special constitutional status and statehood in 2019 when the Indian Parliament abrogated Article 370 of the Constitution.

“The truth is my family just did not have the money to meet my legal expenses,” Zaid says. “And they thought it was best that I stayed incarcerated anyway.”

Two of Zaid’s closest street-fighting friends had been shot dead by police. Moreover, his parents feared he might join a jihadist group.

From 2016 on, government statistics record over 15,000 stone-throwing protesters arrested by police. Even though thousands of these first-time offenders turned amnesties, many remain incarcerated in prisons outside the state. Nearly 200 protesters died in police custody, and hundreds more were left injured.

Even though 27-year-old Shahdar Majid played a much smaller role in these street protests—and served just a few months in jail—he recalls the exhilaration that participation brought. “There is no fear when you are part of a group of hundreds, even in the face of police fire,” Majid says. “As a teenager, you do not fully understand the cause or the consequences it will have on your life.”

Today, a father to three children, Majid sells fruit from a handcart to make ends meet. “I would have liked to finish school and get a job,” he says. “The thing I would like from whoever is elected—make sure my kids get the chance.”

Aijaz Ahmad Sheikh, released from prison around the 2018 panchayat election in Heerpora, had taken a different route to make his fortune. Faced with terrorist threats, no one showed any inclination to contest the election in Heerpora. Aijaz filled out the forms to become the Heerpora sarpanch, and two other members of his street-fighting group contested the election as well. All three were elected unopposed.

However, Aijaz’s life was cut short this year.

Hailing from the Zainapora area of Shopian, Sarjan Ahmad Wagay was another key resistance leader during the 2016 violence. Wagay now faces a contest with National Conference vice-president Omar Abdullah in Ganderbal—north of Shopian—in the second phase of voting in the state. Even as Wagay, out on bail, campaigns wearing a GPS-enabled ankle bracelet, he faces trial on terrorism-related charges.

Though only a few of ‘Generation Rage’ acknowledge the inheritance, they are heirs to deep rifts in Kashmiri politics and society—unresolved for decades. There is no telling, however, just what political form a new politics in the region might take.

Also Read: ‘Call me Gafoor’. This is an unapologetically personal reminiscence of AG Noorani

Jamaat cashes in

Late in the summer of 1944, the young son of one of Kashmir’s storied Sufi families—Saaduddin Tarabali—met with schoolteachers Ghulam Ahmad Ahrar and Abdul Haq Barak in Badam Bagh on the banks of Rambiara River in Shopian.

Kashmir’s Jamaat-e-Islami counts that as its first official meeting—the beginning of its struggle against a Taghuti Nizam or a regime disobedient to God. The party committed itself to combat “moral degradation” and build a social order that revolved around Islam.

That commitment would lead Jamaat-e-Islami into electoral politics, tapping youth resentment by blaming maladministration and corruption on the secularist principles of the National Conference. Then, it positioned itself as the vanguard of the jihad—the patron party of the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen.

In an alliance with newly-elected MP ‘Engineer’ Rashid’s Awami Ittehad Party, this election, the Jamaat-e-Islami is currently lending it’s support to some candidates while distancing itself from Geelani’s political legacy. It is thus again on the opposing side of the National Conference, with Omar Abdullah alleging that it has New Delhi’s support.

Among the ten candidates the Jamaat-e-Islami is supporting is Kashmir University-educated lawyer Ajaz Ahmad Mir, elected on a Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) ticket in 2014 from Zainapora and son of influential former National Conference MLA Abdul Jabbar Mir.

Ajaz has never been a Jamaat member—unlike the other candidates who served the party before a ban on it in 2019.

The Mir family, like many traditional supporters of the National Conference, found itself under attack from the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen jihadists after 1989. “Faced with the large-scale killing of our workers, we even tried allying with the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front,” Mir says. “But our home in Srinagar came under attack 27 times, and we had to flee to Srinagar.”

“Last week, I reminded some senior Jamaat-e-Islami leaders of this background and asked why are they now supporting me?” Mir says. “They said it is because I have served my term as an MLA with integrity, and I spoke up for young people. They wanted to discuss the past, not the future.”

“Despite not agreeing with the stone-pelters who brought down the government in 2018, I do not think that shooting and jailing them is the answer. There has to be a responsible leadership finding political solutions to political problems,” he says.

Like Mir, the major parties in the region—the NC, its Communist Party of India (Marxist) ally, and the PDP—are all seeking measures to rehabilitate the youth involved in the eleven-year uprising. The new Apni Party Shopian candidate, Owais Mushtaq, is also campaigning for the amnesty of the one-time rebels.

On his part, Wasim is not holding his breath. “Lots of politicians visited us after Aijaz was killed and promised to make sure his wife and children would be cared for,” he says.

“I have not seen many of them since the photographers left. The one thing we learned is that parties are all pretty much the same.”

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: Security beefed up in Jammu region ahead of polls but attacks since 2021 point to pattern