New Delhi: For all stakeholders in the plastic industry — from small scale recycling factories to waste pickers — Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement, during his Independence Day address on 15 August, of a “ban” on single-use plastic was akin to another demonetisation.

While a nationwide ban was expected to kick in on 2 October, a government spokesperson has now reportedly said there won’t be a blanket ban but a “phased reduction” in the use of plastic products through “public sensitisation”.

Confusion over what this might mean, however, still looms large over all the stakeholders.

“There’s no clear policy on what single-use plastic is. Even if restrictions do come into effect, which products will it cover? Until there is no clear understanding of what single use plastic is, the industry will remain on edge,” said a manager of a factory in Narela Industrial Complex, in the outskirts of Delhi.

“Most of the recycling we do here is of use-and-throw plastic. The panic created by the proposed ban has forced most units to close,” the manager added. “Since 15 August, we haven’t recycled a single product — it’s like demonetisation of another kind.”

Of the 1,800 factories in the complex, 1,400 are plastic manufacturers or recyclers.

Basant Somani, the chairman of the Narela Industrial Welfare Association, told ThePrint that production in these factories has already dropped by 40 per cent with 25 per cent of the workforce having left since the announcement on 15 August.

“The whole supply chain has been shaken because the value of use-and-throw plastic — which is the bulk of what waste pickers take and what the factories then recycle — has suddenly dropped,” he said.

The demonetisation analogy was echoed in Delhi’s scrap yard at Tikri Kalan, a village bordering Haryana. Rina, a 22-year-old waste picker who spends her time segregating different plastic by hand for Rs 150 a day, said supplies and salaries had whittled down since the PM’s announcement.

“We get all kinds of plastic here, not just the disposable kind,” she said. “But in the past 20 days, no new supplies have come. We’ve been segregating old piles of trash.”

Plastics 101: Recycling or downcycling?

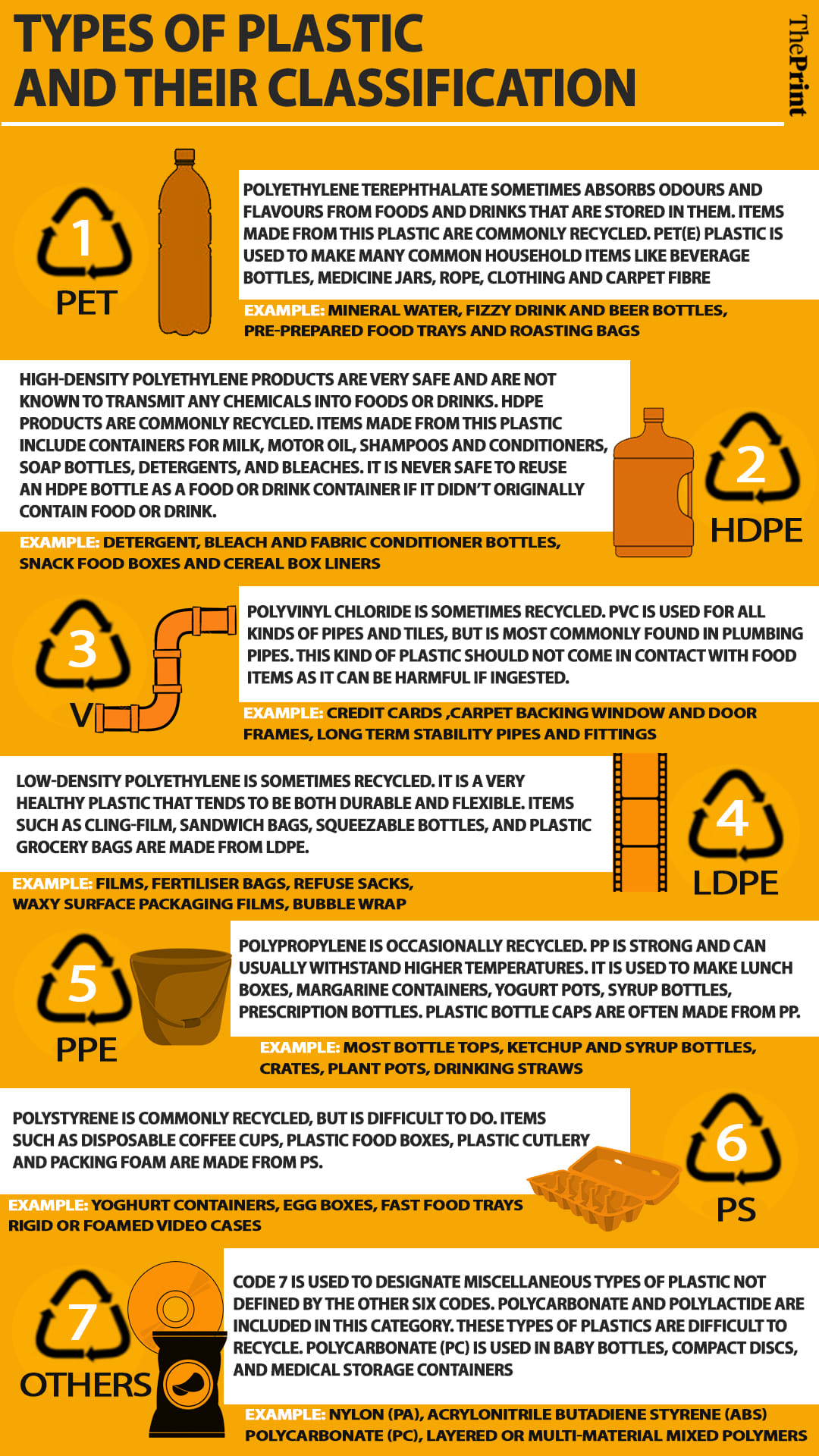

There are seven grades (types) of plastic in the market, most of which are recyclable. Every plastic product features a triangle with a number inside it, indicating which plastic category that a product falls into. According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), India generates 4.4 lakh tonnes of plastic every year, falling into all these grades.

But with no clarity on what all plastic products will fall under the single-use category, there is uncertainty among the stakeholders.

The CPCB labels disposable plastic products as single-use plastic and estimates that they make up 43 per cent of all plastics produced. That could bring plastic water bottles and medicine in the ambit of any government action. The two products, however, are made of polyethylene terephthalate, commonly known as PET, which is the most recyclable of all plastics.

Such is the uncertainty that immediately after PM Modi announced the ban, the PET Packaging Association for Clean Environment (PACE), an industry body, released a full page advertisement in Times of India declaring PET as being 100 per cent recyclable.

“PET plastic can be recycled to form PET products again. So if a water bottle is recycled, it can be processed to make another water bottle,” said Dr Vijay Habbu, polymer expert and technical advisor to PACE. “But in India, it’s against the law to recycle PET back into food or beverage packing for fear of contamination.”

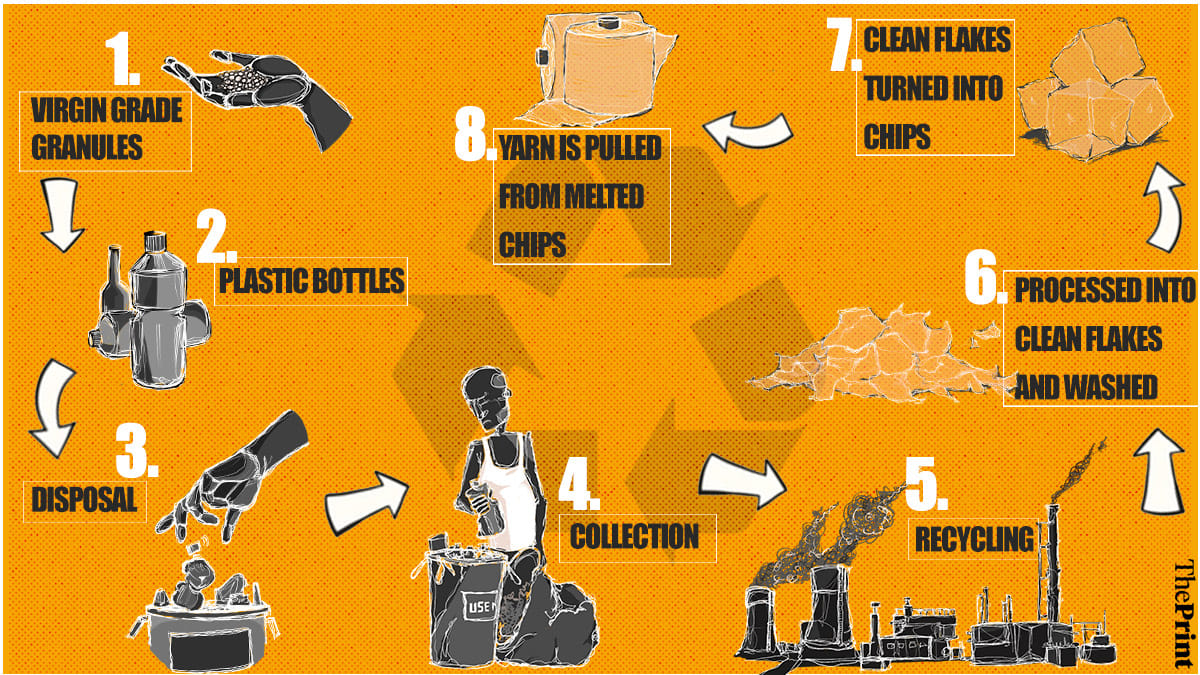

Instead, plastic water bottles are collected by waste pickers and sold to recycling units like the ones in Narela. A survey by the National Chemical Laboratory says 60 per cent of all plastic in India is recycled but Swati Singh Sambyal, programme manager for environmental governance (municipal solid waste) at the Centre for Science and Environment, is skeptical of this number.

“What’s happening in these units is not recycling because in India, making new bottles out of old ones is unheard of,” Sambyal said.

“What they do is downcycling because they make fibre — low grade polyester — out of the PET bottles. A majority of this work is done in the informal sector with no strict regulations, from collection to processing, so the quality of output plastic isn’t going to be the same as the input quality.”

“Besides, after it is turned into textile fibre, the likelihood of the product coming back to the recycling fold is even less likely,” Sambyal added.

PACE, along with the All India Plastics Manufacturers Association, had sought an exemption from the ‘ban’ on PET products such as plastic water bottles.

But PET only forms a small part of all plastics manufactured — around 9 per cent.

Most plastic waste comes from processed foods such as chips, biscuits and confectionery that are wrapped in layered plastic, called multi layered packaging (MLP), sold by large corporates.

MLP is noxious to the environment — it is neither picked up by waste pickers because it lacks value nor is it easily recyclable because of its multilayered nature. And most MLP waste finds its way to mounting landfills, in the depths of oceans while also lining the streets.

In 2016, the Plastic Waste Management Rules were notified and required producers of MLPs to recover the plastic waste from their packaging, called Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). Since its implementation, however, only 49 packaging firms have registered with the CPCB.

Before the government made a statement on the ban, the Confederation of Indian Industry also appealed seeking an exemption for FMCG multi layered packing, because there are no suitable alternatives to it.

Economy vs environment

The Modi government’s desire to curb, if not ban, single-use plastic comes at a time when it simultaneously hopes to double its plastic production and per capita consumption — all by 2022.

India’s per capita plastic consumption rate is 11 kg, less than half of the global average of 28 kg, but the country remains the 15th largest plastic polluters in the world.

Despite banning plastic waste imports from the US in 2015, a study by Pandit Deendayal Upadhyay Smriti Manch, an environmental organisation, found that India imported 25,000 million tonnes of plastic waste from countries such as China, Malawi and Japan in the first 3 months of 2019 alone. The government reintroduced the ban this year but its effectiveness is yet to be seen.

“Why does the government import the same plastic waste that India produces in excess of?” asked Saurabh Bansal, a factory owner from Narela.

“We are producing more plastic waste than we are recycling. Getting more of it, while cracking down on SME (small and medium enterprises) plastic units doesn’t make sense.”

The reason India wants to increase its plastic production and consumption is because it is a common indicator of wealth and development.

“If we are to achieve a $5 trillion economy, growing numbers of plastic products is inevitable, because plastics are used in just about everything,” said Hiten Bheda, chairman of the All India Plastics Manufacturers’ Association’s environment committee.

“A ban or phasing out could thwart that, so the government must consider how it will reconcile the two, especially since there’s no clarity on what kinds of plastic products it wants gone.”

The AIPMA estimates at least 10,000 units could be affected by restrictions on plastic production.

Is there an alternative?

The CPCB has reportedly recommended a ban on 12 single-use plastic products, including plastic bottles for beverages (less than 200 ml), thin carry bags (less than 50 microns), and roadside banners (less than 100 microns).

A ban on these items may not make a significant impact on urban, upper class populace, but it could lead to change in consumer behaviour in more remote areas.

“Loose plastic bags are what most people use to buy loose flour, daals, rice, and other staple products. If those are removed from the market, it’s possible that people will rely more on FMCG products because they come pre-packaged in plastic, and that won’t necessarily solve the problem,” said Vijeyata, a design consultant for urban sustainability systems.

However, experts say packaging alternatives to plastics must be considered carefully.

The carbon footprint of manufacturing paper, steel, glass, cotton, and aluminium all outweigh plastic. The CPCB has instituted guidelines on the production of compostable plastic which is made out of starch, but the cost of producing products from this material are likely to be double, said an official in the Bureau of Indian Standards who didn’t wish to be identified.

Even the Indian ‘kulhad’ — which has a strong advocate in the Modi government — has a higher carbon footprint than plastic, as far as manufacturing is concerned.

With this search for a suitable alternative likely to consume more time and investment, private companies have woken up to their EPR duties and are investing into plastic collection.

On 20 September, several large FMCG companies like Bisleri, PepsiCo and Coca Cola announced plans to invest over Rs 1,000 crore in plastic waste management. The details of the plans, though, are sketchy.

The way forward

As the Modi government pushes forward with its plastic plans, experts emphasise the need for not taking the easy way out and actually fixing the waste management system for better results.

“Plastics which are extremely harmful, and are pollutants should be done away with. But a ban isn’t the only way to manage plastic consumption,” said Bharati Chaturvedi, founder of Chintan Environmental Research and Action Group that focuses on waste collection. “Plastic consumption can also be heavily taxed, for example.”

As for recycling, Chaturvedi says the system depends in large part on waste pickers, whose roles need to be legitimised by both the government and private players.

Incentivising waste pickers to pick up multi-layered plastics could be one way to manage plastic waste.

Bheda says these practices should be done away with, and waste pickers and scrap collectors should not have to deal in the currency of waste or pay for serving the environment.

It’s also crucial to spread awareness on waste segregation and the dangers of keeping MLPs at the household level, where dry plastics are mixed with wet garbage. Mixed waste tends to be dumped in landfills, making working conditions for waste pickers much worse.

But until these choices are actually turned into policies that are inclusive of the existing informal channels, the sense of betrayal among small and medium plastic recyclers is unlikely to recede.

“We neither produce nor deal in plastic that is unrecyclable. This whole industry is self-sufficient, from production, to collection, to recycling. The government has done nothing for us, except fine us, and now ban us,” said the factory manager quoted above.

(Bharati Chaturvedi’s quote has been updated in the report to accurately reflect her stance on the matter)