New Delhi: Since Saturday, chief ministers of two southern states, one from the NDA and the other from INDIA bloc, have flagged concerns over the ageing population in the southern part of the country, urging people in their respective states to have more children.

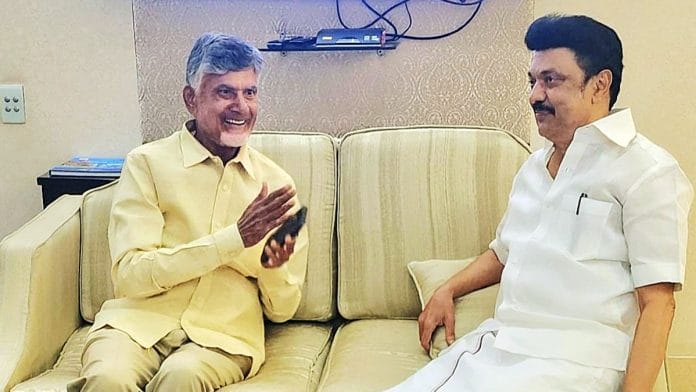

The remarks by Andhra Pradesh CM Chandrababu Naidu and Chief Minister M.K. Stalin of Tamil Nadu came within 48 hours of each other. But this is not the first time chief ministers of two southern states have spoken on the issue.

As ThePrint reported then, during the ninth meeting of the governing council of the federal think tank NITI Aayog held on 27 July this year and chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, chief ministers of some states spoke about the need for a “demographic management” plan to address the ageing population in their states. This was seen as the first instance of states raising this issue at a forum like the NITI Aayog.

Responding to these concerns, Modi encouraged states to initiate demographic management plans to address the issue.

The concerns are not unfounded. India is not only experiencing a rapid decline in fertility rate but is also ageing much faster.

Shamika Ravi, a member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM), says the concern from a longer term perspective is that while India has an ageing population, the median age is still 28.

“That is why we keep thinking we are young. But we also have 120 million people above the age of 60. So, very soon you are going to straddle with lower fertility, a very large dependent population and a very small working population to sustain it,” she tells ThePrint.

That, she says, will also have an economic impact. “… because your young population’s fertility is declining but the ageing will continue and we are ageing fast. We already have 120 million people above 60. If this happened when we were a $10,000 per capita income then it’s one issue but it is happening when we are $3,000 per capita per year. We need a working population to sustain a large, old and very young population as well.”

She also stressed the need for enough resources and financial instruments to cater to a growing ageing population. “You need to invest in core infrastructure, health care, assisted living, etc. The government has acknowledged the issue … you are going to hear about it repeatedly now.” According to Ravi, this is why there is a need to dispel the fear that India’s population is a problem. “In fact, it is our biggest asset.”

NITI Aayog member Arvind Virmani had during the NITI Aayog in July acknowledged that a number of states will witness a reduction in the share of the working population.

“… idea of the persons (some chief ministers) mentioning it is because of the demographic change that is happening. This will accelerate in the next 15 years and of course one aspect of that is ageing but the second aspect is in terms of skills, and the jobs, which will be created in the states where young population is declining relatively or in terms of population of working age … it’s all about the working age population. So, that internal dynamics we have to start thinking about…,” he had said.

Also Read: Global peak, ageing population & low fertility rates — takeaways from UN’s revised population report

Declining TFR & elderly population

By 2021, India’s total fertility rate (TFR) had declined to 1.91 per woman, below the replacement level of 2.1 per woman.

TFR is the average number of children born to a woman in her childbearing years, while replacement level is the level of fertility at which a population replaces itself.

As of 2021, 12 crore Indians—or 8 percent of the overall population—were above the age of 60. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFP) in its 2023 India Ageing Report estimated that India’s elderly population could surpass the population of those aged 15 or below by 2046. According to it, the share of India’s elderly in the overall population is projected to increase from 10.1 percent in 2021 to 15 percent in 2036 and 20.8 percent in 2050.

The report also pointed out that while India’s overall population will grow by a mere 18 percent between 2022 and 2050, the elderly population will grow by 134 percent during the same period. Further, it said the share of the elderly population was higher than the national average in 2021 in “most of the states” in southern India, adding that by 2036 one in five persons in the southern states will be above the age of 60.

Released last September, it went on to highlight that old-age dependency ratio was higher than the national average “in the southern region”.

Viramani says by 2050, India will be in the position where America is now, where the ratio of dependents—elderly to the working-age population—will be the same as in the USA today.

“We need to start creating the institutions and markets from now on. States where the working-age population is declining and the old-age population is rising have started thinking about it, as there is a shortage of labour. These labour destination states have to focus on and be the first to build infrastructure for looking after old people. The labour source states have to worry more about employment and quality of employment, and education, skilling etc.,” he tells ThePrint.

He explains further that India is far from the kind of problem France is facing. “They have a pension system, in which the pension obligations are greater than the pension asset, creating a fiscal challenge. This is true of several states in Europe, whose pension assets are not enough to meet the liability.”

Adding, “So we should learn from this and not get into that kind of a situation. In the US, there is a wide discussion that if they continue at the current rate, pension liabilities are going to exceed pension assets.”

Another factor which is adding to concerns is the declining fertility rate.

The fifth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), conducted over a two-year period from 2019 till 2021, revealed that the total fertility rate (TFR) at 2.0 had for the first time dropped below replacement level. According to it, India’s TFR declined from 2.7 in 2005-06 to 2.2 in 2015-16 and further 2.0 in 2019-21—lower than the replacement rate of 2.1. The findings also showed that the TFR of all states in southern India, and for that matter even in the north and west, is below the national average.

The only exceptions were Bihar, Meghalaya, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Manipur.

Economists say one of the reasons fertility is declining very rapidly at this stage of growth is because more women are joining the labour force, especially in urban areas, and opting to have one child or no children at all.

NFHS-5 data shows TFR among women in urban areas declined from 2.7 in 1992-93 to 1.6 in 2019-21. “The higher labour force participation is directly contradictory to higher fertility … it’s a very long-standing deep structural problem,” says Ravi.

It is also worth noting that in India, the burden of child care as also elderly care is almost entirely on the shoulders of women in India.

“We are a fast nuclearising, fast urbanising society. So child care or any form of care is not shared across generations any more. We do not have joint families like earlier … these are nuclear families where women are bearing all the burden and they are therefore under this kind of constraints. The entire cost of rearing and bearing children but now also the elderly because you have an ageing population is entirely on the shoulders of women,” says Ravi, adding that Indian women are finding it increasingly unaffordable to have more babies.

“That is why you see the choices young couples are making, you are seeing fewer and fewer babies … because it’s burdensome, highly labour intensive work,” she adds.

Yet another factor fuelling these concerns among southern states is the possibility that they might not be treated fairly if and when a delimitation exercise is conducted. Stalin has in the past referred to it as a “sword” hanging above southern states.

This is an updated version of the report

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Educated women are having fewer children. It’s not good for India’s demographic dividend