New Delhi: In 2013, Som Dutt of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) left his job at a bank to take a plunge into politics. He earned Rs 45,000 a month at the time.

Nine years later, the 45-year-old Dutt has won Delhi’s Sadar Bazaar assembly seat thrice, and earns Rs 53,000 as a legislator.

He has a family of three to support, including a 3-year-old son he plans to get enrolled in a government school next year because private schools are expensive. He lives in his father’s two-storeyed house and doesn’t own a vehicle — not even the two-wheeler he had when he was still working at the bank.

His financial situation could get better soon, though — on 5 July, the Delhi assembly passed a Bill to hike an MLA’s salary 66 per cent to Rs 90,000 a month. The last hike for the capital’s MLAs came 11 years ago.

The hike of MPs’ and MLAs’ salaries has been a subject of many public debates, with the political class often facing a backlash when there are attempts to raise their pay.

An analysis of MLAs’ salaries in India shows there are wide disparities among the various states/UTs, not only in terms of basic pay but also in the allowances given to them.

“Many people think MLAs are rich and corrupt but the reality is that in 90 per cent of the cases, the wife or another family member is taking care of the household expenses, such as children’s school fees,” P.C. Vishnunadh, a Congress MLA who represents Kerala’s Kundara constituency, told ThePrint over the phone.

“I’ve been involved in student politics since my college days, so the party trusted me and gave me a ticket,” said Vishnunadh, who first became an MLA at age 28 in 2006. “But I didn’t have the time to earn and collect money for my family. My wife runs a play school in Kerala, and that’s how we take care of our household expenses.”

An analysis of the various state laws on salaries and allowances for legislators as well as news reports shows that Telangana (gross salary Rs 2.7 lakh/month), Maharashtra (Rs 2.3 lakh), Himachal Pradesh (Rs 2.1 lakh), Jharkhand (Rs 2.08 lakh), and Uttarakhand (over Rs 2 lakh) pay higher salaries and allowances to their MLAs.

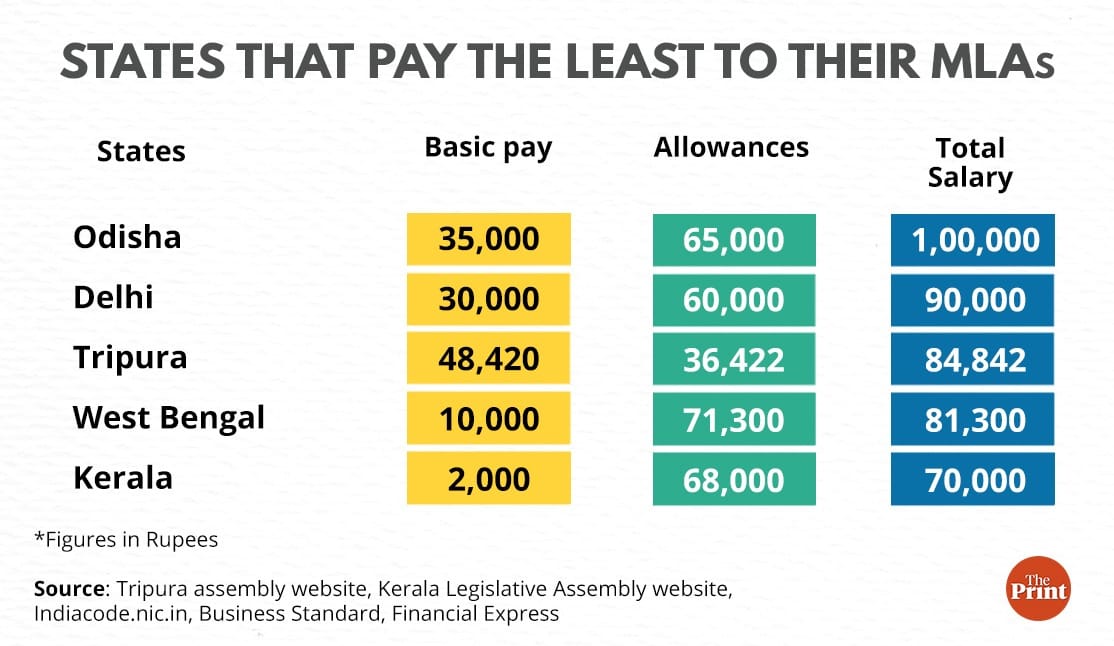

Conversely, Delhi, Tripura, West Bengal, and Kerala are the lowest-paying states/UTs, with MLAs drawing a gross salary of anywhere between Rs 50,000 and Rs 90,000.

Still, several MLAs in the lowest-paying states/UTs say it would be unfair to ask for a raise.

Sreerupa Mitra Chaudhury, the BJP MLA for English Bazar in West Bengal’s Malda, said such a demand would be “unusual”.

“In West Bengal, the state government finds it difficult to to pay government employees their salaries and DA (dearness allowance). They (the state) are also in debt,” she said over the phone. “The economic position is tough. So, as an MLA, I don’t have the courage to say that our salaries should be increased.”

Vishnunadh agrees, saying that asking for raise at a time when his state was going through a “serious financial crisis” would be unfair.

According to an RBI report, West Bengal, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, and Kerala are the most indebted states in the country.

However, political analyst Sanjay Singh said there’s no justification for the pay disparity “because the MLAs everywhere perform the same tasks”. “The assumption that MLAs can earn through other means cannot be ground for [such] low salaries,” he told ThePrint.

Legislators are allowed to pursue other professions simultaneously, but barred from holding office of profit. In 2018, rejecting a PIL that sought to bar legislators from being engaged as lawyers, the Supreme Court said legislators “cannot be styled or characterised as full-time salaried employees”. In 2017 too, the top court had found no merit in a plea seeking a bar on legislators from pursuing other professions.

Also Read: Freebies, bailouts, revival of pension scheme — why many states are at risk of fiscal stress

How much MLAs get paid

Generally, an MLA’s salary consists of fixed (such as the basic pay, which is the standard pay without allowances) and variable components (such as allowances). A total of the two components makes gross pay — that is, the total monthly salary a person makes without deductions.

In addition to standard allowances such as telephone and conveyance, MLAs get something called a constituency allowance, which they use to maintain their office, travel, and take care of miscellaneous official expenses for their constituency.

In some states/UTs, the constituency allowance also includes expenses for stationery, telephone and electricity bills, and other such expenses that are not included in the pay.

An MLA’s salary could also include allowances for travel (both inside and outside the constituency), personal secretary, and housing rent allowance. Some of these, such as HRA, are reimbursed later.

In Tamil Nadu, the monthly basic pay for an MLA stands at Rs 55,000 but allowances — telephone, postal, vehicle, and compensatory — take the gross salary to more than Rs 1 lakh.

After a revision in their pay, an MLA in Delhi will get a gross salary of Rs 90,000 — Rs 30,000 in basic pay, Rs 10,000 in constituency allowance, and Rs 50,000 in other allowances.

Several states/UTs also have an allowance for a typist or a personal assistant, MLAs’ salary amendment acts show.

The basic pay of MLAs itself varies widely across states/UTs.

For instance, the basic pay of a Kerala MLA stands at Rs 2,000, although the addition of allowances can bring the gross pay to anywhere between Rs 50,000 and Rs 70,000. The basic pay of an MLA from Assam is Rs 80,000, but the addition of a constituency allowance brings their gross salary to Rs 1.2 lakh.

Allowances vary too, salary amendment acts show. Some states/UTs, such as Maharashtra, provide an allowance for the driver. Meanwhile, others set a limit on how much an MLA can be reimbursed for fuel, either monthly or yearly.

In Himachal Pradesh, for instance, an MLA with his own vehicle is entitled to be reimbursed for fuel at the rate of Rs 18 per km. Additionally, they are given an allowance of Rs 2 per km for travelling by bus, taxi, or private vehicles.

In Chhattisgarh, MLAs are given Rs 10 per km for using their own vehicles to travel. Additionally, railway passes and air travel are sponsored by the state government.

But MLAs say their fuel allowance is often insufficient, especially given the rising prices.

“For example, the diesel coupon allowance that all the [Kerala] MLAs get was decided when diesel prices were at Rs 60, but after a rise [in fuel prices], it is insufficient,” Vishunadh said. “In my case, I have almost exhausted my diesel allowance due to frequent travels in my constituency, and much of the year is still left,” he said.

An MLA from Delhi who did not want to be named agreed.

“We’re supposed to get Rs 2,000 a month as travel allowance if we use our own vehicle. Itna toh do din mein hi khatam ho jayega (this will be exhausted in just two days),” the MLA said.

Even in Telangana — the state that pays most — legislators say that the money they get is often insufficient to cover their expenses.

Sanjay Kumar, the MLA for Jagtial from the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS), said legislators often need to travel to their constituency to engage with their voters. “The amount we get from the government wouldn’t last a week,” he said. “As MLAs, we have to spend a lot from our own pockets as well.”

Mukesh Ahlawat, an MLA from Delhi’s Sultanpur Majra, said his salary alone would be insufficient to cover his expenses.

“When I was not an MLA, I remember googling the salary [of a legislator]. It showed that an MLA gets Rs 2.10 lakh as the gross monthly salary. However, when I joined, I realised that the reality was different,” he added. “I run my own school and a paying guest accommodation, so I don’t have to worry too much about making ends meet for my family, but this amount is insufficient.”

Also Read: ‘Lauta do purani pension’: The steady growth of Old Pension Scheme agitations across India

‘Unfair to demand more’

In West Bengal, an MLA gets Rs 21,870 at the beginning of each month — Rs 10,000 in basic salary, Rs 4,000 in constituency allowance, Rs 3,000 as compensatory allowance, and Rs 5,000 as telephone allowance — with the remaining components said to get credited in the subsequent days.

But MLAs say that allowances often get delayed. Manoj Tigga, a BJP MLA from Madarihat, said that legislators received their allowances for March and April in July.

MLAs in low-paying states such as Kerala and West Bengal, however, are divided over whether to ask for a raise. Many MLAs ThePrint spoke to admitted that managing expenses in their salary was hard but remained reluctant to demand a pay hike.

Chaudhury said MLAs knew what they were getting into when they decided to contest elections.

“MLAs’ jobs are 24×7,” she added. “We chose this as a service to the nation. We’ve knowingly contested elections and taken on these hardships.”

Moloy Ghatak, the Labour Minister in West Bengal’s Mamata Banerjee government and the MLA for Asansol Uttar, agreed.

“It might be less, but we don’t work for a salary. Everything is free for us. Accommodation, traveling, food,” he said. “I was a lawyer before. I left the chance to make hefty amounts of money and came here to contest elections. This is not a profession, it’s social work.”

Some legislators disagree. An MLA from the ruling NDA in Sikkim said the lack of a designated development fund for the state’s MLAs meant that they often have to pay out of their own pockets.

“We get around Rs 1,65,000, which includes housing, travel allowances, and a driver’s salary. People think that we are from the ruling party so we get money from the Centre, but that’s not true,” he added. “Everything is managed by us within this amount.”

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Giving up on NPS a tragedy for state govts. DB pensions are ad hoc, delay fiscal stress