Thiruvananthapuram: As shankhs are blown at dusk, a row of Hindu priests begins their ceremony, moving large lamps in slow, circular, synchronised motions to the rhythm of bells and chants.

The Ganga aarti, a daily ritual in places such as Varanasi and Haridwar, has been drawing massive crowds to a small town in Kerala’s Malappuram district.

The ritual, performed every evening on the banks of the Bharathapuzha in Thirunavaya, a town around 30 km from the district headquarters, was one of the highlights of the Maha Magham, also popularly known as the Kerala Kumbh Mela, held between 18 January and 3 February.

“Aarti has been a crucial factor in attracting people. It’s a visual treat. We didn’t plan it as a carnival, but purely as a visual experience. The people behind it are the same crew behind the Ganga aarti in Kashi,” said one of the organisers, requesting anonymity.

The first Kumbh in Kerala’s history was organised by Uttar Pradesh-based Juna Akhara, which claims to be India’s largest monastic order and organiser of the same event in Prayagraj.

Held in the Muslim-majority Malappuram, the organisers projected the event as a revival of the ancient Maha Magham, or the historical Mamankam festival, held on the riverbank over two centuries ago.

However, historians contest this claim and call the Mamankam a display of power, trade, and politics rather than a religious event. The Kerala Kumbh, some say, is similar to the north Indian Kumbh and is part of the Sangh Parivar’s grand project of religious revivalism to polarise society, aiming to introduce Hindutva elements into the local festival.

“This is a concerted effort to stitch a falsified history into a very culture-specific and local event,” says K.P. Sethunath, a state-based political analyst.

Sethunath said that choosing a Muslim-majority district for the event was a carefully thought-out decision. Muslims account for around 70 percent of the population of Malappuram.

He added that holding the event in Kerala for the first time was similar to the transformation of Ganesh Chaturthi from a household event in Maharashtra into a community celebration with political significance by the right wing.

The event, held months before crucial assembly polls, also saw visible endorsement from the state’s BJP and the RSS, while the Congress and the CPI(M) remained silent.

But the organisers dismissed the criticism and said the event was for society at large and not for any particular religion.

They called the event a huge success, saying it drew over 20 lakh devotees, mainly from Kerala and Tamil Nadu, as well as other states. They also announced similar events every year, with a Maha Kumbh Mela at the same location in 2028.

According to their official website, the chief patrons of the event are Sri Mata Amritanandamayi, Hindu spiritual leader and founder-chancellor of Amrita University; Kerala Devaswom Minister V.N. Vasavan; and Acharya Mahamandaleshwar Swami Avdheshanand Giri Maharaj, head of the Juna Akhara.

“Our primary aim was just for all of us to come together without the difference of caste or religion. It’s for the state,” said Swami Abhinava Balananda Bhairava, one of the organisers.

ThePrint reached out to the office of Devaswom Minister V.N. Vasavan, but his personal secretary declined to comment and did not respond to a request to meet the minister on the matter.

Also Read: Why Mahayuti’s Tapovan plan ran into a tree. Opposition to it goes beyond Nashik Kumbh ‘Sadhugram’

The event and its many makings

The Kumbh Mela, translated as the festival of the sacred pitcher, is held at Prayagraj (Uttar Pradesh), Haridwar (Uttarakhand), Nashik (Maharashtra), and Ujjain (Madhya Pradesh) at different time intervals.

It is held on the banks of the Triveni Sangam (the confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna, and the mythical Saraswati), as well as along the Ganga, Godavari, and Shipra rivers, respectively, based on the legend that drops of amrita (nectar) fell in these rivers during the Samudra Manthan (churning of the ocean).

According to D.P. Dubey, professor of ancient history at the University of Allahabad and author of Forever Prayaga: The Site of Kumbha Mela (2025) and Prayaga: The Site of Kumbha Mela (In Temporal and Traditional Space) (2001), the Kumbh Mela in Haridwar is mentioned in Puranic texts, but there was no mention of the event at Prayag in the Puranas.

He added that the festival held in Nashik was referred to as the Simhastha Mela in different texts, such as the Brahma Purana and Skanda Purana.

“There was no tradition of Simhastha Mela at Ujjain,” he said.

He added that the festival in Ujjain began after Ranoji Shinde, founder of the Scindia dynasty in the early 18th century, who played a key role in the Maratha conquest of Malwa and established his capital at Ujjain, requested sadhus and akharas to start the festival in Ujjain.

He said the period after the 2000s witnessed the commercialisation of the event, which broke its traditional 12-year cycle.

Dubey said that many new Kumbh Melas have emerged in recent years, including an annual Kumbh Mela in Chhattisgarh’s Rajim since 2004 and another in Bihar’s Begusarai district since 2012.

Backed by their respective state governments, these events are promoted as religious tourism, generating high revenues.

According to a February 2025 Press Information Bureau release by the Uttar Pradesh government’s Department of Information and Public Relations, the latest Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj had a record footfall of over 450 million people. The event also saw a stampede in which at least 30 people died, according to official figures.

Claiming to be India’s oldest and largest monastic order, the Varanasi-based Juna Akhara is the primary organiser of the Prayagraj Kumbh Mela.

According to its official website, the Juna Akhara was founded in the 7th century CE by Adi Shankaracharya and follows Shaivite monastic orders, with the word ‘Juna’ meaning ‘oldest’.

However, Dubey said the order was earlier called the Bhairav Akhada and was viewed as a security threat during British rule. During a crackdown in the Bundelkhand region, the group found asylum in Banaras.

He added that following the 1809 Hindu-Muslim riots (the Lat Bhairav riot) in Uttar Pradesh, the order rebranded itself as the Juna Akhara to project itself as the oldest tradition. He said the order receives institutional support from changing governments and maintains political neutrality to ensure this.

The Kerala ‘Kumbh’

Organisers of Kerala’s first Kumbh Mela said the event drew over 20 lakh people over two weeks. ThePrint reached out to the Malappuram SP’s office for official figures, and the numbers are awaited.

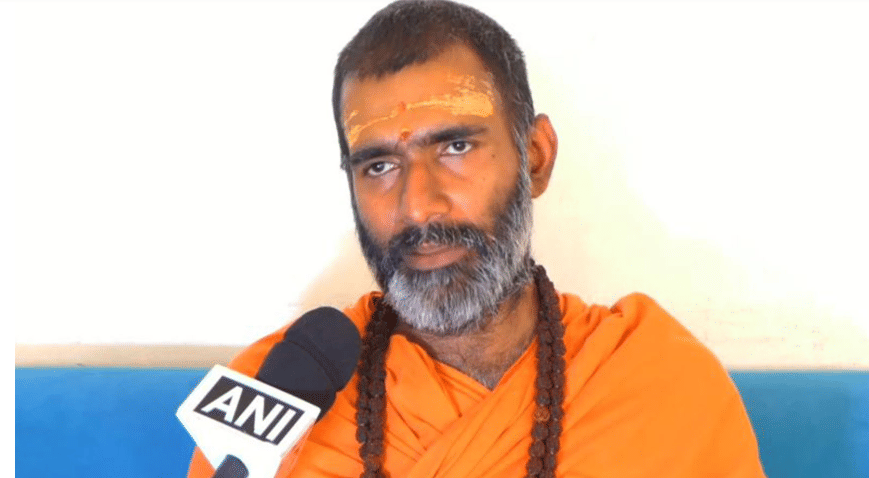

According to the event’s official website, a key reason for holding the event in Kerala was the consecration of Swami Anandavanam Bharati Maharaj as a Mahamandaleshwar in the Juna Akhara, with special responsibility for south India.

“In the backdrop of continuous challenges being raised against Sanatana culture and moral values in South India, the akhadas of North India had conceived and decisively planned this move, of which Swami Anandavanam Bharati’s assumption of authority was a part,” it says.

Hailing from Thrissur district, Swami Anandavanam Bharati Maharaj, earlier known as P. Salil, was a former journalist and a member of the Student Federation of India (SFI), the students’ wing of the ruling CPI(M).

The event also drew attention for the presence of Avantika Bharati, a member of the Juna Akhara and the daughter of a late Naxalite in the state.

“He had many non-bailable cases and went and attended the Kumbh Mela to evade arrest. Later, it became a passion. He is a person who travels extensively,” the organiser quoted earlier said.

The organiser added that Anandavanam Bharati is currently not involved with any organisations or communities, which helped give the event its universal appeal.

The organisers said preparations for the event began only in November 2025, in coordination with local Devaswom Board officials and functionaries associated with the Thirunavaya Navamukunda Temple on the riverbank. The team submitted an official letter seeking permission on 14 November.

According to the organisers, the Kerala Kumbh Mela, or the Maha Magham festival, is a revival of the ancient Maha Magham festival practised at the same location over two centuries ago.

The first sacrificial rite (yajna) for the welfare of the world was performed under the direction of Brahma, with all gods in attendance, and was repeated once every 12 years, the organisers told ThePrint. After the reign passed to human beings, the event also became cultural and commercial, a display of power, eventually evolving into the Mamankam, which too ceased to exist over 250 years ago.

The organisers say they are reviving the Maha Magham festival as a “call to defend Sanatan (eternal) culture against growing challenges”, and that some rituals had been held locally in Thirunavaya since 2016.

According to historians and multiple records, the Mamankam was a major socio-political avenue for the Zamorin, or ruler of Calicut, to display his sovereign power.

The festival’s main events included an international trade fair involving merchants from Arabia, China, and Greece, alongside intellectual contests, sports, and folk-art performances.

It is popularly depicted as the site of ritualised martial conflict, where Chaver suicide warriors from Valluvanad would attempt to assassinate the Zamorin to reclaim the right to conduct the festival.

However, the current Maha Magham festival has many similarities to the Kumbh Mela organised in northern India.

Visuals from the event show saffron flags at every nook and corner, along with flex boards of Lord Ram, and devotees and sadhus taking a holy dip (Magha snanam), participating in rath yatras, and chanting the Narayana japa, along with pujas by different groups and castes of the Hindu religion.

K.N. Ganesh, a Kerala-based historian known for his research in pre-modern history and a former professor of history at Calicut University and chairperson of the Kerala Council of Historical Research, said the Maha Magham and Mamankam festivals were different events conducted at different locations.

“The Mamankam in Thirunavaya was prevalent between the 14th and 18th centuries and held once every 12 years. It was held in Thai Masam (the 10th month of the Tamil calendar, between January and February), from Pooyam to Magham. We may call it a riverine festival, as it was conducted on the banks of a river,” says Ganesh.

“But before that, there is no mention of a similar event being held in Thirunavaya. On the contrary, there are mentions of a Maha Magham festival in Thrikkariyoor (Ernakulam district) in Keralolpathy on the banks of the Periyar,” he says, adding that it was also held once every 12 years based on the Jupiter cycle, though its timeline is unclear.

According to Ganesh, the Maha Magham festival was originally part of river worship for rain at the beginning of summer. Later, it continued during dynastic rule, based on the belief that a good ruler would bring prosperity.

But the Mamankam festival held in Thirunavaya had clear political significance, Ganesh added, as it reinstated the Zamorin’s power over the river and the region.

“The new event is just a replica of the North Indian Kumbh Mela. There is not much clarity on the rituals of the Mamankam festival,” he said.

“Many rituals were conducted at different places. Aarti is not a ritual familiar to Kerala communities. River pujas are also not very common. In Thirunavaya, there is nimanjanam (immersion of ashes in water), which families conduct at their own time,” he added.

He said Mamankam was not a temple-centred festival, though temples exist nearby, and that it saw active participation from the Muslim community.

State-based writer and documentary filmmaker, O.K. Johnny, said the event was part of sangh parivar’s grand project of religious revivalism to polarise society.

“To connect Mamankam to the Kumbh Mela is itself a historical distortion. Mamankam was a trade-related fair during the time of the Samoothiri,” said Johnny, adding that the event is a part of a larger issue of all religious groups trying to grab political power in the state.

Also Read: Taking a leaf out of Yogi’s book: Inside CM Fadnavis’s high-voltage plans for 2026 Nashik Kumbh

Controversy and politics

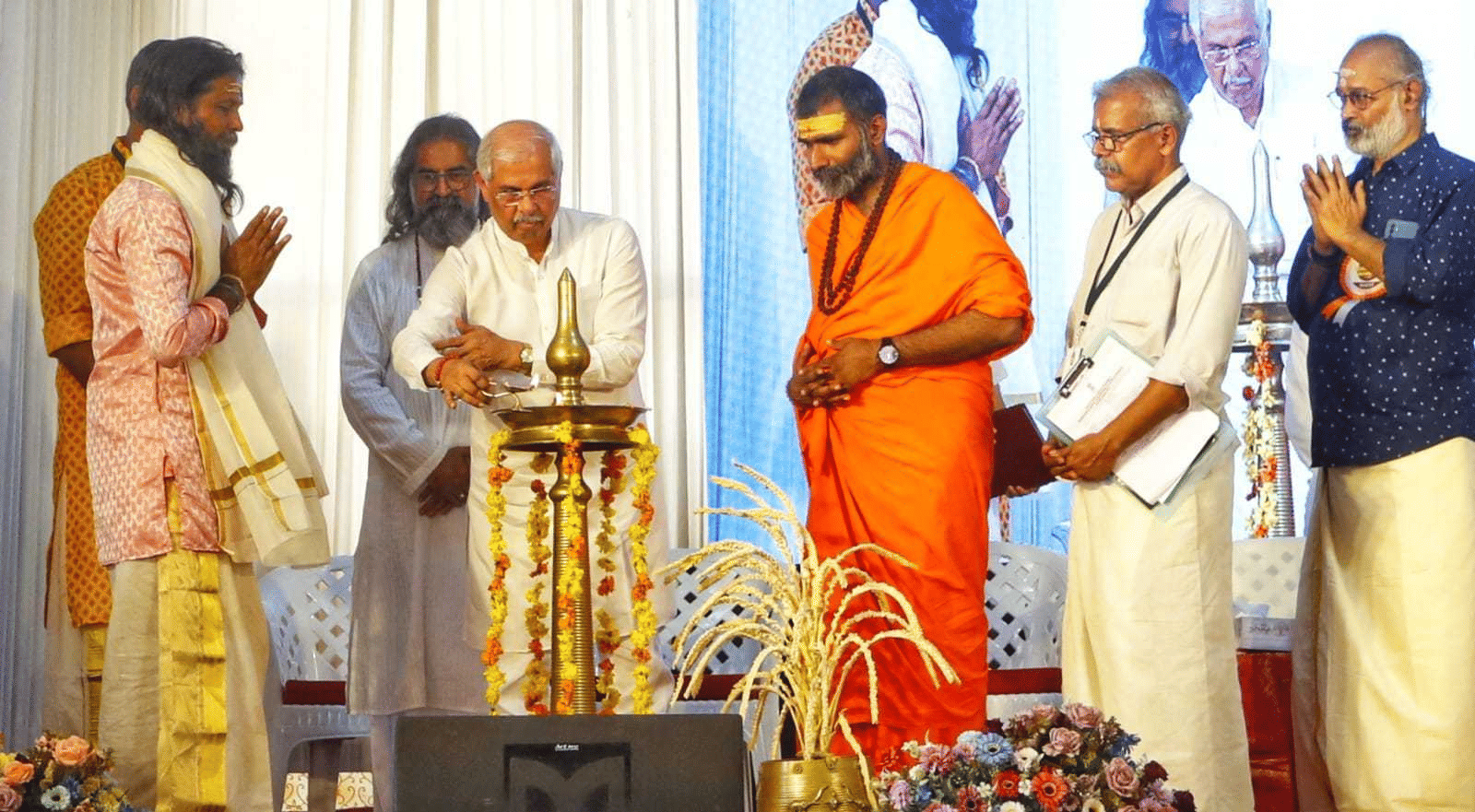

Though officially inaugurated by Kerala Governor Rajendra Arlekar on 18 January, the two-week event found itself at the centre of controversy even before that.

On 8 January, the Thirunavaya Village Officer issued a stop memo, halting the construction of a temporary bridge on the river, citing a lack of permission and violation of the Kerala Protection of River Banks and Regulation of Removal of Sand Act, 2001.

The organisers soon held a press conference in neighbouring Thrissur district, alleging that the move was an attempt to sabotage the event at the last minute and asserting that they would continue.

Soon after, senior BJP leader Kummanam Rajasekharan, in a Facebook post, called the action illegal and a violation of religious freedom.

The organisers approached the Kerala High Court, which directed an inspection led by the Executive Engineer of the Public Works Department in Tirur and the District Police Chief to ensure security arrangements.

The Malappuram district collector later issued instructions to the organisers to adhere to green protocols and safety measures, after which construction was resumed.

Support was not limited to Rajasekharan. Senior BJP leaders K. Surendran, Sobha Surendran, and the BJP’s lone MP Suresh Gopi visited the event at different times during the two weeks, while BJP state President Rajeev Chandrasekhar called it “a wait of over two centuries”.

“Seeing lakhs of Hindu devotees, spiritual masters, and revered ascetics arriving here from various parts of India fills me with great happiness and pride. This revival has once again restored Kerala to a central place on India’s spiritual map,” Chandrasekhar said in a social media post.

“We must never forget our roots, heritage, and cultural history, for it is in them that our true strength resides,” he added.

The event also saw the active presence of volunteers from the RSS-affiliated Seva Bharati in cleaning and other management roles.

KPCC functionary and Congress spokesperson Sandeep Varier said the party was not against any religious community or organisation’s right to hold gatherings as part of their faith.

He said the event, held in Malappuram, became a testimony to the secular nature of the district and its people, countering the popular BJP narrative branding it “Pakistan”.

“I opine that the sadhus who attended from the north should take back the story of secularism in Malappuram to their native places, especially when Bajrang Dal activists attacked a textile shop over its name in Uttarakhand,” Sandeep said.

He added that local residents were welcoming of the attendees and that the event dispelled the narrative propagated by the BJP about the district.

Sandeep added that organisers must establish the credibility of the event and its historical claims. He said historians should initiate discourse on the issue, which could then provide a platform for political parties to engage.

“Religion is a weapon for the Sangh Parivar to divide people. All mainstream parties, including the Congress, view this event with caution. We saw controversy created over the bridge memo. I don’t believe the Sangh’s presence will yield political gains from this event, as people in Kerala are wise enough to understand this,” he said.

ThePrint reached out to CPI(M) State Secretary M.V. Govindan through calls and messages, but received no response till the time of publishing. CPI(M) State Secretariat member M. Swaraj also declined to comment.

“Either they are maintaining a conspicuous silence, or they are ignorant. The CPI(M) has ceased to be a Communist party and is only trying to protect its eroding Hindu vote base,” Sethunath said.

He added that while the event may not have an immediate impact on state politics and culture, it could lead to long-term polarisation.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: Israeli devotee to sceptical journalist—book launch explores human side of Kumbh

Very biased and twisted article. Whole Govt system tried to sabotage the event from the beginning.

I am unable to fathom the rationale behind the views espoused in the article. India is a free and secular country. Why should organization of a festival be seen in a negative lens. What is wrong if it is held in a muslim majority district? If people are appreciating and enjoying the organized events, why cast aspersions on it.

The same set of journalists bat for free propagation and conversion of majority populance in other regions. They do not oppose conversions that occur on gifting money rather than a spiritual or religious choice. Dont they spread disharmony n polarize society?

It is this double dealing and aversion to celebration of Hindu religion which has led to ordinary Hindus label terms such Pseudo-sickular and turn to more right wing elements that respect their identity. No one is ready to take the seemingly self-righteous, neutral, and pompous commentary.

This is a good thing 💝 loving how librandu professors are trying to undermine this festival . It’s okay. Mamta tried but she failed now she is building temple Sooner or letter she will be gone. That will happen in Kerala also. Enjoying this melt down 🫠