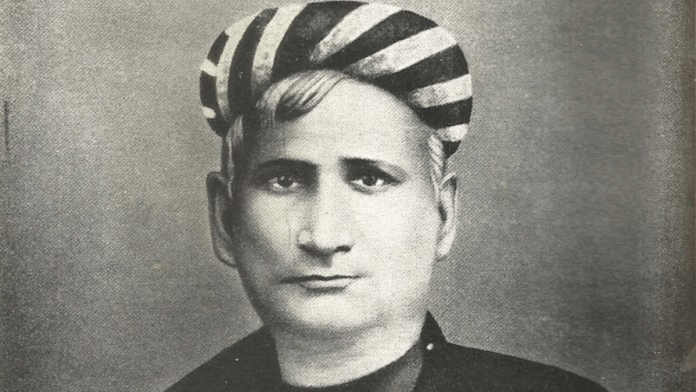

New Delhi: In the year 1874, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, the writer of Vande Mataram—the song which is both revered and disdained for its explicitly idolatrous content—wrote a largely-forgotten essay on idolatry in his journal, Bongodarshan.

“Idolatry is anti-science. Wherever idolatry prevails, knowledge does not advance,” Bankim claimed in the essay. “It constrains man’s mind and diminishes the growth, improvement and development of human personality.”

Neither the Greek philosophers and scientists, nor the Aryan sages who had, according to him, promoted the advancement of knowledge, were idolatrous.

Around the same time, in the early 1870s, Bankim wrote the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram. This was not necessarily inconsistent. The first two stanzas arguably contained no idolatrous content.

They lay purposelessly for years—unpublished and unread—speaking to nobody but the poet himself.

Cut to 1881. In Bongodarshan itself, Bankim serialised his most popular and politically significant novel, Anandamath. Vande Mataram found its way into the novel.

This new Vande Mataram, which unlike the previous one, was meant for public consumption, became longer—Bankim added two additional stanzas to his poem. But curiously, the poem also became idolatrous.

“Thy image we raise in every temple/For thou art Durga holding weapons of war/Thou art Kamala (Laxmi) at play amidst lotuses,” now wrote the man, who had until just a few years ago, found idolatry to be detrimental to the growth of scientific inquiry and man’s development.

Decades later, by the 1920s, the song, which had initially been in the words of historian Sabyasachi Bhattacharya “a purposeless creation of a poet musing and singing to himself”, had become a communal war cry—an enduring bone of contention between the self-professed spokespersons of Hindus and Muslims.

It was no minor disagreement. In an article published in 1938, in which (then leader of the All-India Muslim League and later the founder of Pakistan) Mohammad Ali Jinnah summed up “Muslim demands”, he said Vande Mataram was not only idolatrous “but in its origin and substance a hymn to spread hatred for the Musalmans”. The song was unacceptable to Muslims as a national anthem, he contended.

A century later, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has claimed that it was the removal of “significant verses” from Vande Mataram that led to India’s partition. The government, which is already celebrating 150 years of the song, Monday discussed the song in the ongoing Winter session of Parliament.

What were these verses Modi was referring to? What was the contention around them? How did a vehemently anti-idolatrous Bankim become the writer of the song whose idolatry became one of the most divisive issues during the national movement?

And from Bankim’s private musings in the 1870s to a spontaneous slogan of the revolutionaries in the 1900s; from an irreconcilable communal dispute of the 1920s and 1930s, to A.R. Rahman’s rousing rendering in the late 1990s—what is it about Vande Mataram which continues to stir the Indian nation?

Also Read: Bankim Chandra — the man who wrote Vande Mataram, capturing colonial India’s imagination

‘A silent soliloquy’

There is considerable agreement among scholars that Vande Mataram was originally written between 1872 and 1875, at least five to six years before the song made it to Anandamath.

The song, largely written in Sanskrit, broke into a spontaneous line in Bengali, the author’s native tongue. “Why then is my Mother so powerless?” Bankim asked in the poem, almost as Bhattacharya said, in “the voice of intuition muttered almost as a silent soliloquy, conveying profound inward pain.”

The poem, as mentioned above, had no initial purpose. “In writing the poem Vande Mataram, Bankim in his loneliness was like a man talking to himself,” Bhattacharya wrote. “That accounts for that he did not publish it for many years, that it has linguistic blemishes, that it defies conventional prosody, and perhaps also that it spoke to the heart of so many people.”

In the poem, Bankim sought to animate the hitherto inanimate idea of the motherland, thereby personifying and imbuing the concept with deep emotive content.

In the shorter, original version of the poem, the motherland is the “giver of bliss”; she is richly watered and richly fruited, her nights rejoice in the glory of the moonlight. Perhaps most significantly, the poem says that the motherland has “70 million sons” to defend her, a figure which included the combined Hindu-Muslim population of Bengal, according to the 1871 census.

Even Rabindranath Tagore, who first composed music for Vande Mataram and sang the song before a gathering of the Calcutta Congress in 1896, said in a letter to Jawaharlal Nehru in 1937: “To me the spirit of tenderness and devotion expressed in its first portion, the emphasis it gave to beautiful and beneficent aspects of our motherland made a special appeal…” There is nothing in these first two stanzas that could possibly offend any sect or community, he contended.

But this was the story of only half the song. In 1881, as it made its way to Anandamath, Vande Mataram became unmistakably Hindu in its references and analogies. The “Mother” who had hitherto only been the “giver of bliss” was now Durga holding “ten weapons of war”.

As argued by historian Tanika Sarkar in her paper ‘Birth of a Goddess: Vande Mataram, Anandamath and Hindu Nationhood’, the fact that Vande Mataram was written over two phases, and that the two parts are remarkably distinct in the religious imagery they evoke, has allowed the hymn to be separated and discussed without any reference to the novel. This, Sarkar argues, is erroneous since the song’s re-inscription within the novel did give it entirely new political meanings.

Given that the novel unambiguously reproduced the trope of Hindus as an effeminate, fragmented people and Muslims as “barbarian invaders” who had long suppressed the Hindu spirit, it is not difficult to guess who the motherland is protecting herself against with the ten weapons of war in her ten hands.

Why did Vande Mataram change so fundamentally in the intervening years?

First, as mentioned above, the first version of the hymn was not for public consumption. As a song written by a poet “talking to himself”, the song was not prescriptive in anyway. Anandamath, on the other hand, as Sarkar argues, “was more a performance, an iteration, making something happen with words”. In it, by extension, Vande Mataram, too became a prescription for the “Muslim problem”.

Second, as argued by Bhattacharya, there has been a consensus among scholars that literarily and intellectually, there was a radical “early Bankim”, and a conservative “late Bankim”.

The “late Bankim”, it has been argued, was deeply influenced by the French philosopher Auguste Comte, who had famously proffered that for a system to rise, it must not be at odds with the inherent culture and nature of people. Bankim quoted this to argue that religion and its reform must be consonant with the “nature” and culture of the people.

He, therefore, as Bhattacharya argued, takes the archetype of the motherland, which had existed in classical Hindu mythology and culture, and suffuses it in the idea of the nation imported from the West.

Also Read: Tagore, Bankim & the battle for Bengal’s soul—BJP caught in its own cultural crossfire

‘A war cry’

“It was thirty-two years ago that Bankim wrote his great song and few listened,” nationalist revolutionary Aurobindo Ghose wrote in 1907. “But in a sudden moment of awakening from long delusions, the people of Bengal looked round for the truth and in a fated moment somebody sang Vande Mataram. The mantra had been given and in a single day a whole people had been converted to the religion of patriotism.”

“The Mother,” Ghose said, “had revealed herself.”

By 1907, the “silent soliloquy” of a poet talking to himself that had for the first three decades of its creation only been an object of admiration among a small circle of connoisseurs and literary enthusiasts, had been turned into a mantra, a slogan of war.

The change had come about with the Swadeshi movement, which almost spontaneously adopted the hymn as its theme song, as then Viceroy of India Lord Curzon split Bengal into two in 1905. As a Swadeshi song, it was not popular among revolutionaries alone. Indeed, on Rakshabandhan in October 1905, it was Tagore who led a Vande Mataram procession as its lead singer.

However, as the movement of the revolutionaries gathered steam in the first two decades of the 20th century, Vande Mataram indeed became their war cry. There is scarcely ever a revolutionary document that is not headed with “Om Bandemataram”, observed J.E. Armstrong, a police officer on special duty investigating militant nationalist operations in 1917.

J. Ramsay MacDonald, the future prime minister of England, observed that the “deification of India” was at the root of the “psychology of the unconstitutional movement” (of the revolutionaries).

The appeal of the war cry was not limited to Bengal. Through the first decade of the 20th century, both Vande Mataram and Anandamath were translated widely across the country.

From Punjab to Madras, the vernacular press was agog. Banned journals exclaiming Vande Mataram began to be imported illegally from as far as Berlin and Geneva. Visual representations of the mother country as portrayed in the song were circulated in calendars hung in offices and homes.

In 1907, in Rajahmundry in the Madras Presidency, students began to wear Vande Mataram badges, with Europeans complaining that street boys were paid to shout Vande Mataram at them. Mill workers in Bengal screamed Vande Mataram at European assistants to demand better working conditions. In some cases, even criminals shouted the slogan as they looted. That the administration banned the utterance of the slogan only intensified its appeal.

As argued by Bhattacharya, by this time, the complex set of ideas and imagery in the song were all abbreviated into a “simple but effective message of fealty to a cause and defiance of foreign rulers”.

The British played no small part in this. As they grappled with the Vande Mataram problem, they looked frantically for its origins. G.A. Grierson, an Indian Civil Service official, wrote that the mother was “no other than Kali, the goddess of death and destruction”. British journalist and historian Valentine Chirol said the song “demonstrated a readiness to appeal to the ‘grossest and the most cruel superstition of the masses’”.

As the British got a whiff of the Muslim elite’s discomfort with the slogan, as a classic divide and rule strategy, its idolatrous character was magnified.

Muslim scepticism

In 1907, an anonymous Bengali pamphlet printed on lurid red paper came into circulation. “Not a single Muhammadan should join the perverted Swadeshi agitation of the Hindus… Oh Muhammadans, sing not Bande Mataram!”

There were multiple reasons behind the Muslim scepticism towards the Swadeshi Movement and Vande Mataram. Only the most obvious was the now well-known hostility towards Muslims espoused in Anandamath.

Muzaffar Ahmed, one of the founders of the Communist Party of India, for instance, wrote in his autobiography that Bankim’s novel was “full of communal hatred from beginning to end”. Meanwhile, the song Vande Mataram, he said, was “unacceptable to a Muslim boy, a monotheist like me”.

There were other reasons too. First, among the educated Muslims in Bengal, there was a pro-Partition attitude on account of the “declared policy of the East Bengal government to prefer Muhammadans to Hindus in government services”.

Second, the greatest proponents who had elevated Vande Mataram to the status of a national song were the militant nationalists or the biplabis, among whom exclusion of Muslims was a widespread practice, as though done on principle.

Third, there were already cases of Vande Mataram being shouted not just at the British, but also outside mosques.

From the second decade of the century, as the communal faultlines hardened between Hindus and Muslims, Vande Mataram came to be criticised by prominent publications of Muslims.

“The only and supreme Allah’s kalima Allah-o-Akbar when combined with the Hindus’ anthem to mother India, Vande Mataram, was pushing Muslims towards idolatry (kufr),” said Islam Darshan, a journal published in 1920. For the Muslim press, Bankim was now undisputedly a “Muslim hater to the inner-most core”.

Also Read: Bankim Chandra Chatterjee gave India the means to express itself. Sri Aurobindo echoed him

Whose national song?

It was in this context that the question of Vande Mataram as the national song emerged in front of the Congress. If it left Vande Mataram out altogether, it risked antagonising the scores of Hindus who saw nothing wrong with the hymn. If it kept it as it is, Muslims would feel affronted.

Confused, Nehru asked Tagore what was to be done. In his response, Tagore said: “I freely concede that the whole of Bankim’s Vande Mataram poem read together with its context is liable to be interpreted in ways that might wound Moslem susceptibilities, but a national song, though derived from it, which has spontaneously come to consist only of the first two stanzas of the original poem, need not remind us every time of the whole of it, much less of the story (Anandmath) with which it was accidentally associated.”

“It has acquired a separate individuality and an inspiring significance of its own in which I see nothing to offend any sect or community.”

It was a time of passion. Few had Tagore’s patience to differentiate between the different stanzas of the poem, and between the meaning of the poem by itself and its meaning in the context in which it was placed in Anandamath.

Despite the icon that he was, Tagore faced the historical equivalent of trolling for suggesting breaking up Vande Mataram. “Since I have been born in Bengal, the typhoon of name-calling is like the accustomed breeze of my homeland to me,” he responded.

Yet, Tagore’s advice was taken by the Congress. The same year, the working committee of the Congress said the “past associations, with their long record of suffering for the cause, as well as popular usage, have made the first two stanzas of this song a living and inseparable part of our national movement and as such they must command our affection and respect”.

There was nothing in the first two stanzas to which anyone could take exception, and as for the other stanzas, they were barely known and hardly ever sung anyway, it said. “They contain certain allusions and a religious ideology which may not be in keeping with the ideology of other religious groups in India.”

Seeking to strike what could have been the best possible balance at the time, the committee said: “Taking all things into consideration therefore, the committee recommends that wherever Bande Mataram is sung with perfect freedom to the organisers to sing any other song of an unobjectionable character, in addition to, or in place of, the Bande Mataram song”.

In 1939, even Mahatma Gandhi, who had in the first decade of the 20th century praised Vande Mataram, said in an issue of the newspaper Harijan, “I would not risk a single quarrel over singing Vande Mataram at a mixed gathering. It will never suffer from disuse. It is enthroned in the hearts of millions.”

Of course, the compromise could not prevent the partition of the subcontinent. But even three years after Independence, it was obvious that the song could not be exorcised from the new nation’s consciousness.

On the last day of the last session of the Constituent Assembly on 24 January, 1950, its president Dr Rajendra Prasad gave a decision from the Chair. While Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana would be the national anthem, Vande Mataram, “which has played a historic part in the struggle for Indian freedom, shall be honoured equally with Jana Gana Mana and shall have equal status with it”.

As pointed out by Bhattacharya in the biography of Vande Mataram, this decision was not debated and voted upon. While one does not know if this was because there was difference of opinion within the Congress and the Constituent Assembly about the selection of the anthem, what is a matter of record is that both Jana Gana Mana and Vande Mataram were sung at the end of the deliberations of the Assembly on that day.

(Edited by Nida Fatima Siddiqui)

Also Read: Why Bankim Chandra is seen as the original ‘Hindu nationalist’, long preceding Savarkar