New Delhi: An in-depth study of the Indian and Chinese education system has found that India’s early emphasis on humanities, shaped by colonial-era priorities, has slowed its economic progress. In contrast, China’s broader diversification of vocational and professional disciplines, particularly engineering, education, and medicine, has been a key driver of its higher growth rates and lower levels of inequality since the 1980s.

The paper—titled ‘The Making of China and India in the 21st Century: Long-Run Human Capital Accumulation from 1900 to 2020’ and published on the economic blog Marginal Revolution Saturday—examined the educational paths of the world’s two most populous countries and aimed to provide a foundational framework for studying “human capital” composition, that is, skills developed through each country’s education system.

“China’s educational development path has been more closely aligned with the goal of fostering economic growth. Indeed, it is to this path that we should attribute China’s higher rates of growth rate from the 1980s onward as well as its lower levels of economic inequality,” said the research paper by scholars Nitin Kumar Bharti and Li Yang of the Paris School of Economics’ World Inequality Lab.

“India, by contrast, initially laid a much greater emphasis on the humanities, in part due to the human capital needs of the colonial administration. Given India’s distance from the technological frontier, the specific features of the Indian strategy have not been wholly conducive to higher rates of growth.”

By analysing a wide range of historical reports and educational surveys, the researchers compiled a unique dataset spanning the past 120 years, highlighting three striking differences when comparing the long-run educational approach in China and India: bottom–up vs top–down, quality vs quantity, and diversification of education.

The paper argues that these differing approaches had significant consequences for the economic progress of the two countries, particularly in terms of inequality.

“As a result of these divergent strategies, educational inequality is much higher in India, accounting for one-quarter of observed wage inequality, compared to 5-12 percent in China,” the research paper said.

Also Read: Why Centre’s ‘Bharatiya Khel’ initiative for Indian sports in schools is seeing little uptake

Bottom-up vs top–down

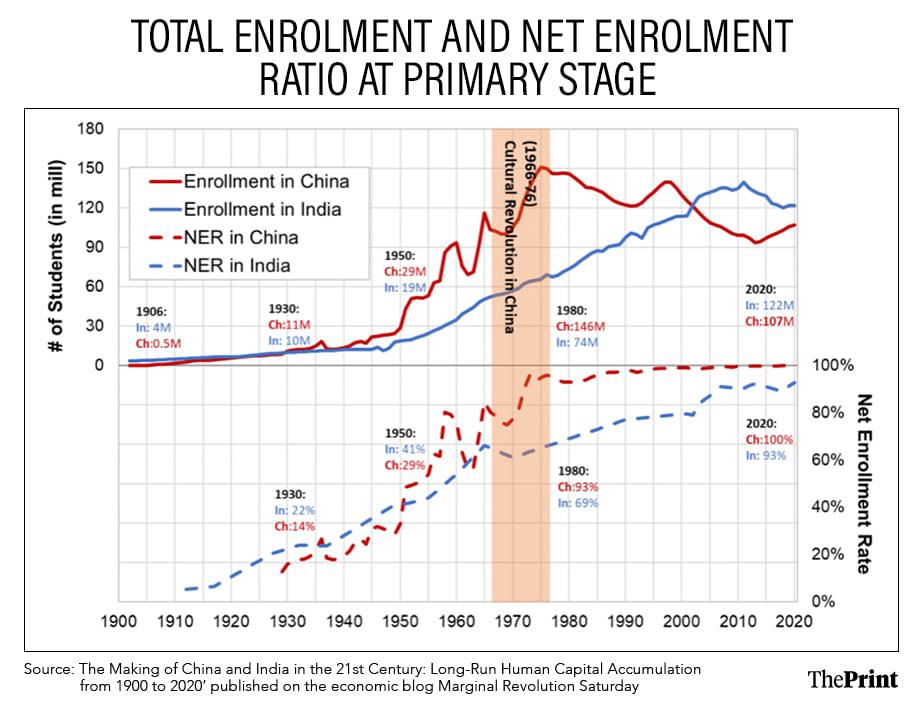

According to the research paper, China initially focused on primary-level mass education from the early 1900s, before Communism. During the 1960s-1980s, under Communism, the emphasis shifted to secondary-level education and finally to tertiary-level elite education, from the 1980s onward.

On the other hand, during the British Raj era (until 1950), India placed its primary focus on secondary-level education. In the post-colonial Socialist phase, the emphasis shifted to tertiary-level education and, finally, to the primary level after the 1990s (post-liberalisation).

The research paper said that due to the lack of consistent efforts to promote primary education and the limited development of adult education after Independence, India maintained a 37 percent illiteracy rate in its 1970s cohort (children born in that period), whereas China successfully eradicated illiteracy in the same cohort.

“This progression is reflected in various metrics, including enrolment ratios, teacher-to-population ratios, and spending patterns, to name but a few. Policy debates also mirror these priorities, with China focusing on compulsory education from the early 1900s, whereas India only began serious implementation post-1990,” the research paper said.

For instance, the research showed, in 1994, India’s gross enrollment ratio (GER) for doctoral education was more than double that of China (0.11 percent vs 0.05 percent). However, by 2020, the situation had reversed, with China’s GER reaching 0.65 percent, surpassing India’s 0.31 percent.

“China’s bottom-up approach during the Communist era contributed significantly to this achievement. As the illiteracy rate continued to decrease in subsequent cohorts in India, a trend toward convergence is observed between the two countries, for both illiteracy rate and education Gini (a measure of inequality in educational attainment),” the paper highlighted.

Prioritising quantity over quality”

China also prioritised quantity over quality during the initial expansion of its education system, while India pursued slow and steady expansion while maintaining quality at each education level.

At the primary level, until the 1950s, China increased its gross enrolment rate, during which quality deteriorated. It was only after attaining a high enrolment rate (>70 percent) that it started improving the teacher-pupil ratio by hiring more teachers, and from the 1980s onwards, it started improving teachers’ salaries (relative to national income per capita).

In India, since the beginning of the 20th century, the debate has focused on improving quality by increasing teachers’ wages and creating a few “model” institutions of high quality, the paper said.

“However, not hiring enough teachers led to a deteriorating teacher-pupil ratio. Post-1990, India shifted its stance, focusing more on increasing quantity (i.e. enrolment rates), which came at the cost of declining quality—an aspect that has been well-noted in the literature.”

The research paper said that both China and India dramatically increased their educational investment from the early 20th century, with education investment ratio (EIR) growing by over 700 percent between the 1930s and 2010s. By the 2010s, educational spending in both countries reached around 14-15 percent of per capita national income.

In the 1930s, China spent just 3 percent of Gross National Income (GNI) on primary education and India 2 percent, with China also spending 3 percent on secondary education compared to India’s 17 percent. By the 2010s, China allocated 21 percent of per capita GNI to primary education and 24 percent to secondary education, while India spent 17 percent on both. Tertiary education spending in both countries rose from under 1 percent to 9 percent.

It further highlighted that while overall trends in EIR growth were similar, China’s investment fluctuated significantly between the 1950s and 1980s, largely due to the disruptions caused by the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. In contrast, India’s EIR growth was steadier during this period.

Over the 20th century, both countries shifted from elite, quality-focused education to mass education. By the 2010s, nearly all children were enrolled in primary education, two-thirds in secondary, and 40 percent in tertiary.

China first prioritised expanding access (quantity) and then focused on improving quality, particularly through the Teacher-Pupil Ratio (TPR). India, influenced by its colonial legacy, emphasised quality, investing in highly trained teachers. The data highlights how both countries balanced access expansion and quality improvement in their education systems.

“The multiplicative decomposition of EIR enables us to examine quality and quantity trends simultaneously while also shedding light on associated trade-offs as education expanded,” it said.

Diversification of education

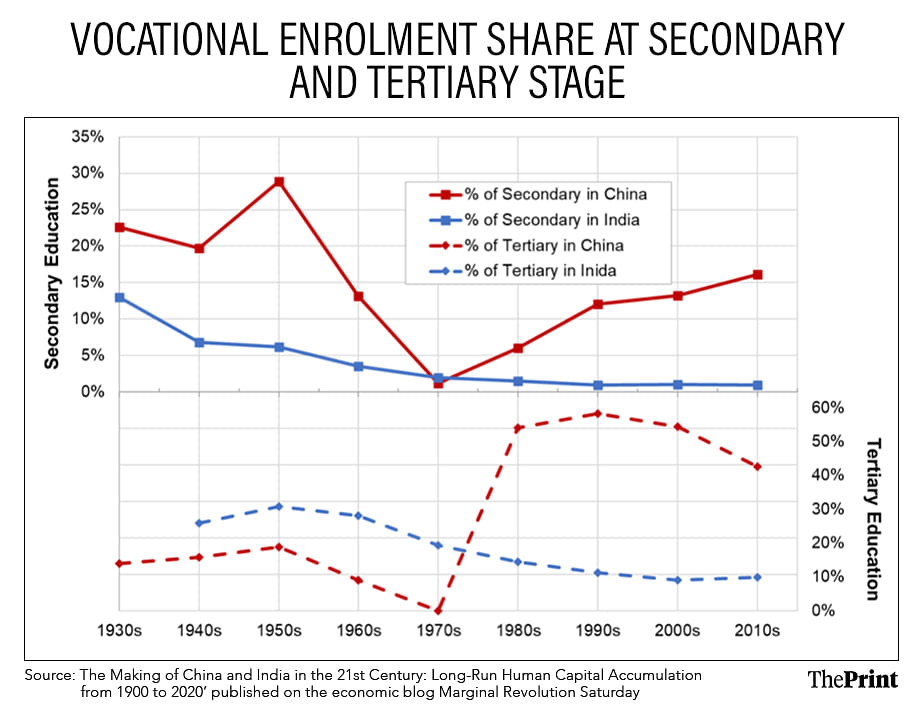

In pre-1950s China, vocational education was closely linked to industrialisation and military needs, the study said. During the late Qing Dynasty, specialised colleges were established to support military objectives, which laid the foundation for tertiary vocational education in the early 20th century. Under the Republic of China (1912-1949), vocational education expanded at the secondary level, culminating in the 1932 Vocational Education Law, which established a formal, independent vocational system at the tertiary level.

In contrast, vocational education in pre-Independence India lagged behind due to the country’s limited industrialisation under British colonial rule. India was primarily seen as a supplier of raw materials and a consumer of finished goods, with education focused mainly on serving the elite, the study said.

Furthermore, vocational training was not prioritised and government schools did not offer vocational courses at the secondary level, resulting in limited models for private institutions to follow. This historical gap helps explain the significant difference in vocational education enrolment between China and India at the secondary level.

During the 1940s, India had a higher share of vocational education at the tertiary level than China, the report said. The paper also highlighted China’s significant growth in vocational education from the 1950s onwards, particularly after the 1980s with the country’s economic opening. By the 1980s, 54 percent of tertiary students and 6 percent of secondary students were enrolled in vocational programmes.

Over the next three decades, the focus shifted slightly, with vocational enrolment at the tertiary level declining while secondary enrolment grew. By the 2010s, 49 percent of tertiary and 16 percent of secondary students were in vocational education. In contrast, India’s figures remained much lower, with only 10 percent of tertiary and 1 percent of secondary students in vocational education.

The paper attributed China’s success in vocational education, especially after 1990, to factors such as decentralised management, state-owned enterprises ensuring industry participation, mandatory private sector involvement (under the 1996 Vocational Education Law), improved teacher training, and financial support initiatives like free secondary vocational education, introduced in 2009. Many of these features are now being integrated into India’s vocational education policies, according to the research findings.

Engineering vs humanities

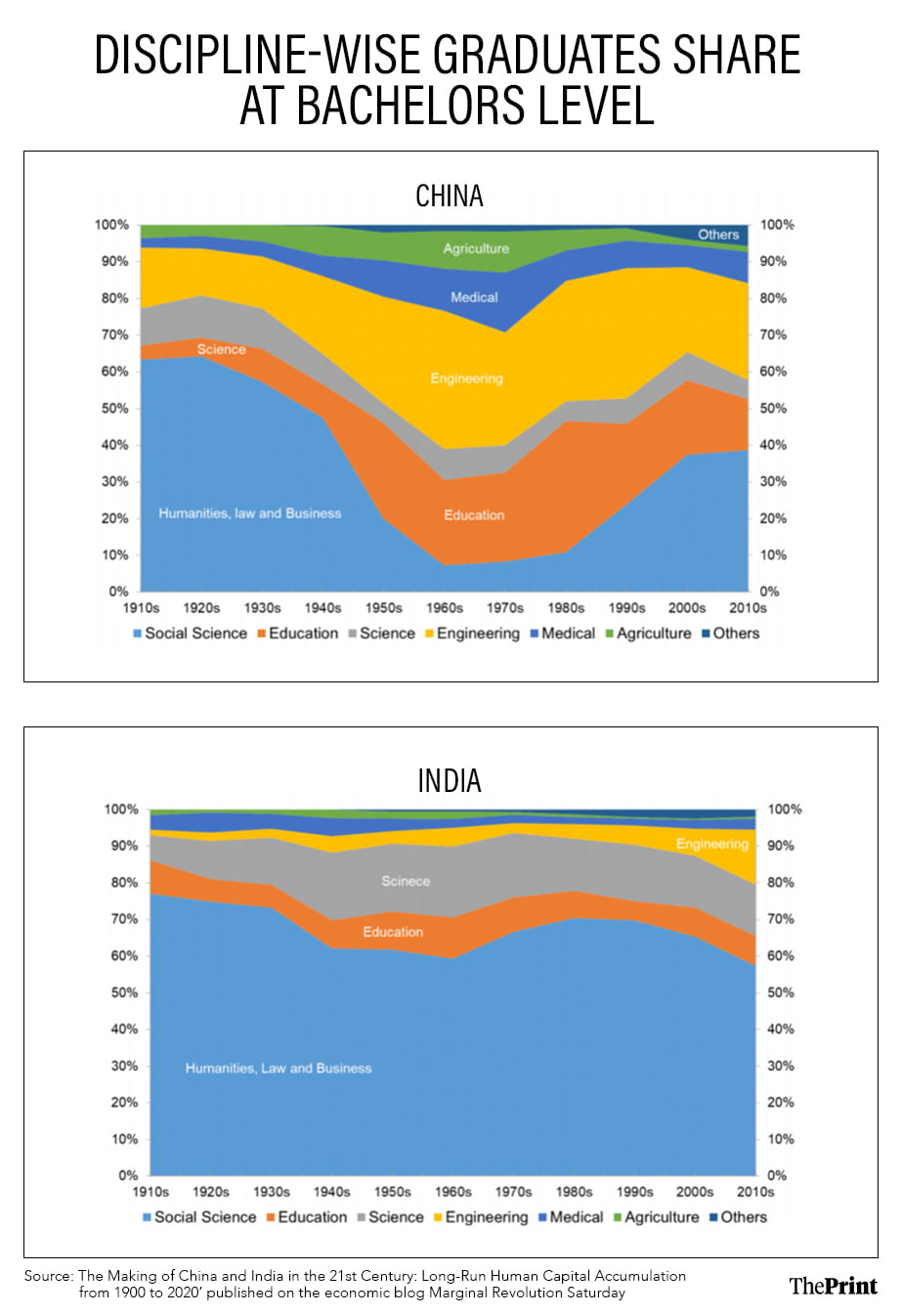

According to the research paper, China and India have produced distinctly different types of graduates, with China’s graduate distribution undergoing significant shifts over time.

In China, the share of social science graduates sharply declined from over 60 percent in the 1920s to less than 10 percent by the 1960s, coinciding with a growing focus on engineering and medicine.

Following the economic reforms of the 1980s, the share of social science graduates surged to 39 percent by the 2010s, while the proportion of engineering graduates dropped from 36 percent in the 1990s to 26 percent.

In contrast, India’s graduate distribution remained relatively stable until the 2000s, with social sciences and sciences comprising over 80 percent of all graduates. Engineering’s share began to rise in the 2010s, growing from 7 percent to 15 percent, but it remains smaller than in China, research showed.

Historically, China has placed greater emphasis on engineering. Reforms in the 1930s, aimed at supporting economic development, led to a focus on science, engineering, and medicine. By the 1940s, 20 percent of Chinese graduates were in engineering, compared to just 3 percent in India—a trend that has continued into later decades. China has consistently maintained a higher proportion of engineering graduates compared to India.

The research further reveals that China’s Gross Graduation Rate (GGR) for bachelor’s degrees in engineering has consistently exceeded India’s since the 1930s, except during the 1970s due to the Cultural Revolution. In contrast, India generally maintained a higher overall GGR for Bachelor’s degrees across all disciplines.

China’s higher education system also saw a significant expansion in education and medicine from the 1950s onwards. While both countries had similar shares of graduates in these fields in the early 20th century, China dramatically increased the share of education graduates from 9 percent to 26 percent and medicine graduates from 6 percent to 10 percent in the 1950s.

India’s share of education graduates rose modestly, while its share of medical graduates fell from 5 percent to 2 percent. By the 2000s, China’s GGR for education and medicine still lagged behind India’s. However, by the 2010s, China’s GGR for education was 50 percent higher than India’s, and its GGR for medicine was 250 percent higher.

(Edited by Sanya Mathur)

Also Read: What is Cabinet-approved PM-Vidyalaxmi & how it will benefit 22 lakh meritorious students each yr

Left’s votebank is largely drawn from ‘humanities’ background. So, they nurtured ‘humanities’ and neglected STEM and vocational training. The masses were lured with ‘welfare’ schemes instead of making them employable.

Of course it did.

Instead of focusing on basic sciences and technology, we focused on humanities. And we lagged behind China on all counts.