Mumbai: India’s strategy during the turbulence of the Trump tariffs was defined by restraint and long-term thinking, rather than emotional or reactive diplomacy. The government deliberately chose not to be swept up in the rapidly spreading fire and unpredictable communications from Washington, DC, speakers at a panel discussion by the Asia Society India Centre said Monday.

The panellists said that regardless of fluctuations in personality or tone from the White House, India viewed the United States as an indispensable partner, economically, technologically, and strategically.

“We’re reading Trump right. Initially, there was shock. But I think there is a predictability in unpredictability. So, what you see is that we’re not responding to every tweet that is coming out or whatever he (Trump) is saying,” said Deepa Wadhwa, a former diplomat who has served as an ambassador in several countries, such as Japan and Qatar, and was part of Monday’s panel discussion.

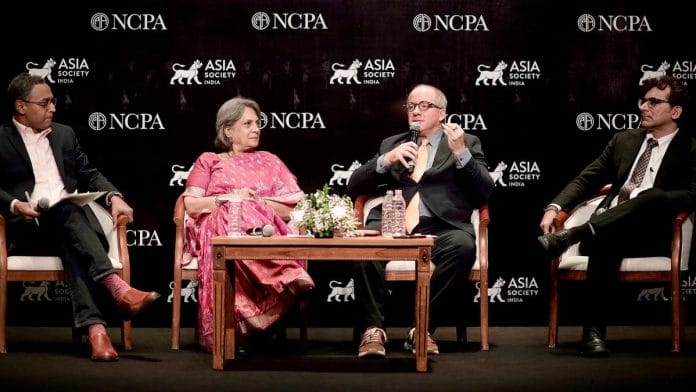

The Asia Society India Centre’s panel discussion, “Year in Review: Tariffs, Turbulence and a Turn in the East,” held on 24 November at Mumbai’s National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA), delivered a clear message. It was that the global order was entering a period of profound unpredictability, shaped by technological disruption driven by Artificial Intelligence (AI), geopolitical rivalry, and weakening international institutions.

Other than Wadhwa, Duncan Clark, Global Trustee of The Asia Society and author of ‘Alibaba: The House That Jack Ma Built’, and Sajjid Chinoy, Head, Asia Economics at J.P. Morgan, were part of the panel discussion, moderated by journalist Govindraj Ethiraj.

Founded in 1956 by John D. Rockefeller 3rd, the Asia Society now has centres in major cities, such as New York, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Sydney, Seoul, Mumbai, and seven other nations. It’s the India Centre, with its nearly 500 members, that focuses on South Asia’s complex and rapidly shifting economic and strategic environment.

India’s response to Trump’s policies

Over the past year, India has had to navigate a sharply deteriorating trade environment with the US, driven by steep new tariffs, which have been inflicting real pain on exporters. In August 2025, Washington, DC, imposed an additional reciprocal levy—25 percent—on many Indian goods, citing trade barriers. Later, it added another 25 per cent “penalty tariff”.

India’s broader bilateral trade deal with the US has also hit a wall. Despite hopes of an interim agreement, sensitive issues, particularly US demands to lower tariffs on American agricultural or genetically modified foods, have stalled progress. At the same time, New Delhi is grappling with a different kind of blow—a newly introduced one-time $100,000 US H-1B visa fee for first-time applicants, which went into effect in September. J.P. Morgan’s Sajjid Chenoy applauded the Indian government’s diplomatic maturity and domestic reforms but stressed that the country’s demographic advantage was narrowing.

“India’s response is very mature, and I think very well guided. India and the US have huge common economic interests over the next 20 years. We don’t want to ruin that relationship for the three or four years of a Trump presidency. India has to grow, and given our demography, we have a very narrow window,” he said. “Sustained progress”, he added, is going to be difficult as “the challenge for India is, in a de-globalising world, how do you grow exports?”

He further went on to say, “At a time when globalisation is retreating, and the world is turning away from free trade—triggered by the US—India will require deep structural reforms in land, labour, and power, as well as a competitive export strategy.”

Former diplomat Wadhwa pointed out that India recognised early on that reacting to every provocative statement would only generate instability in the relationship.

Instead, India opted for what she called “strategic calm”—an approach that allowed policymakers to distinguish the noise of presidential rhetoric from the underlying continuity of American institutions and India-US cooperation.

This differentiated India from several other nations, which, according to her, quickly adjusted to Trump’s style. She described it, saying, “Unlike all the other countries, which fell in line. We didn’t do it. We waited.”

Reviewing the AI-powered year

The panellists underscored AI’s extraordinary global momentum, but cautioned that its rapid advance would shape the emerging world order in more profound ways. While its capabilities promise unprecedented productivity and innovation, they warned that without responsible deployment and stronger regulatory guardrails, the technology could deepen inequalities and displace large segments of skilled workers.

Wadhwa identified the commercialisation of AI as a major accelerator of geopolitical instability, transforming global economics and power structures faster than policymakers could adapt. “What we have seen in this year is that the effects of AI are coming to bite us,” she noted, warning that governments had not yet grasped how fast or how disruptively AI was reshaping society.

Duncan Clark expanded on this by highlighting China’s role as a technological powerhouse. Shenzhen’s innovations, such as electric vehicles, smart hardware, and AI models, are no longer aimed solely at developing markets but are increasingly influencing Western consumers, as well. “Chinese tech is here. It’s here to stay,” he claimed. “If you make everything and sell everything, you start to have influence.”

He pointed to the rise of Chinese shipping dominance and the global spread of AI technologies, noting, “DeepSeek started it. Alibaba’s QEN is now the most popular open-source AI product in the world.”

Chinoy sounded a particular alarm on labour markets, noting that AI-driven automation might soon displace educated workers in a “second wave” of disruption. He cited Taiwan’s experience of booming GDP but collapsing consumption as an example of growth decoupled from job creation.

New world order

A central theme Wadhwa returned to was the need to restore a coherent global order anchored in predictable rules. “You want order in the system, you need to have some rules that sort of govern the world,” she said, arguing that rules-based stability was now a prerequisite for peace.

But the institutions tasked with delivering that order were faltering, she said, adding, “The rule-making body of the world, whether it’s the UN or the WTO, has failed in a way…has failed us.” This, she said, reinforced India’s case for long-pending multilateral reforms, especially at the UN Security Council, which she called “absolutely anachronistic, doesn’t make any sense in today’s world”.

Wadhwa said the post-World War II framework, which was built on sovereignty, rule of law, free markets, and economic interdependence, was weakening simultaneously. These long-standing “pillars of stability,” she cautioned, were now “under assault,” making cooperation harder and increasing the risk of global miscalculation.

Chinoy offered a parallel warning—near-term economic momentum was masking long-term fragilities in the global system. The “five pillars” that sustained global prosperity since 1945—free trade, open labour flows, strong institutions, limited state intervention, and open immigration—were eroding, and at the same time, threatening not only US leadership but the broader order that enabled decades of growth, according to him.

Wadhwa stressed that China’s role in this shifting landscape was systemic. “China’s military, economic and technological prowess is asserting itself,” she said, adding that China was reshaping global rules and power balances. Meanwhile, Clark described the US and China as “split-screen economies”, each technologically dynamic, yet structurally fragile.

Chinoy, however, said there was an opportunity for India amid all that. “With a young workforce as the world ages, booming remote-work–driven services, China exiting labour-intensive sectors, and global firms pursuing China+1 diversification, India can become a major services and manufacturing hub, if it undertakes rapid and sustained reforms.”

(Edited by Madhurita Goswami)

Also Read: 172 countries & counting, India looks to hit new record in rice exports. But there’s a flip side