Leh: The youngest of four siblings, most people remember Sonam Wangchuk as his mother’s shadow. But to his brothers, he was just unbearably curious.

“He would argue endlessly, debate with us over everything. The questions never stopped, so many that it became exhausting,” recalled the eldest of the four brothers, Phunshuk Wangchuk, who now runs a resort in Ladakh’s Uleytokpo village. “Even as a child, he believed in a society different from the one he saw around him.”

What felt like an irritating personality trait to them sowed the seeds of the man he would become.

As he grew into activism for education and environmental reform, Sonam Wangchuk’s family worried about his health because he often went on long hunger strikes that stretched on for days.

Their worst fears came true in a way they had never imagined when the educationist, innovator, environmentalist and activist was placed under the stringent grip of the National Security Act.

Wangchuk’s arrest came two days after demonstrations in Leh turned violent, with four people killed in clashes with security forces.

The Ladakh activist, who called off his 35-day hunger strike to demand statehood and Sixth Schedule protections for Ladakh, distanced himself from the violence, saying it damaged a peaceful struggle of five years.

“He debates and argues for sure, but he also listens and decides. But violence and Sonam are on opposite ends. Even as a child, whenever he would be annoyed with someone, he would tell me, ‘Go fight for me’,” said his brother, Sonam Dorjay, a postgraduate in Economics who now works as a farmer.

Wangchuk stands accused of instigating the 24 September violence in Leh with his “provocative speeches” and failure to calm protesters demanding Sixth Schedule status blamed for clashes with security forces.

The Leh Apex Body, which was spearheading the protest along with the Kargil Democratic Alliance, has now said that the talks with the Centre will remain suspended until peace is restored in Ladakh. It has criticised the government’s narrative on Wanghuck and also demanded his release.

‘He is our Gandhi’

As he remains locked in a Jodhpur prison, his family and neighbours back in the tiny village of Uleytokpo, some 70 km from Leh, worry about his well-being.

Wangchuk was picked up from the tiny village that is home to just 71 people as he was taking a walk by a stream. He had asked Tsetan, his second-oldest brother, to drive him down to Leh to meet the hospitalised men who had suffered bullet wounds in police firing, but the plan couldn’t materialise.

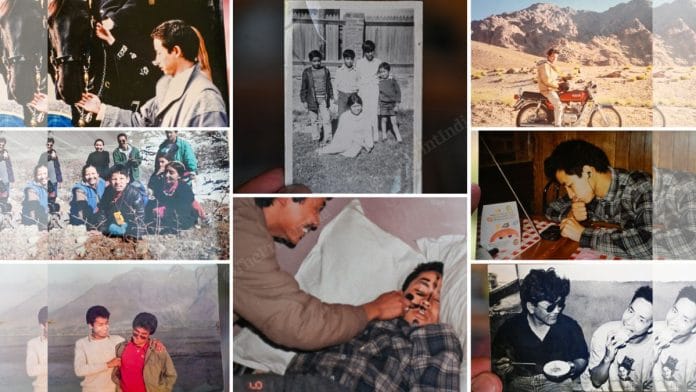

As they wait, the family takes comfort in wandering down memory lane. His eldest brother calls out to his daughter, Jigmet, to fetch old photographs.

“Look at how he used to sleep like a baby,” said Tsetan, chuckling as he held up a picture of a teenage Sonam fast asleep while a mischievous relative doodled over his face.

The room erupts in laughter briefly amid the sound of chants in the background, for the 59-year-old’s safety and health.

They then move on to a black-and-white photograph from Wangchuk’s college days. His eyes sparkled with mischief as he posed mid-bite, caught between eating and grinning at the camera. The family smiles at the memory of him as a carefree young man.

“He was always different,” Tsetan added with a laugh. “We would ask our father for pocket money, but Sonam stopped the moment he joined the National Institute of Technology in Srinagar to study mechanical engineering. Instead, he was out there giving English coaching, standing on his own two feet.”

It is almost hard to reconcile that the man whose serious face now flashes across television screens, his speeches looping endlessly on news channels, was once so playful and candid.

A neighbour, 79-year-old Tsering Yangchen, whom Wangchuk would call “Aama (mother in Ladakhi)”, said, “We haven’t been able to eat and sleep properly since he was taken away. That boy is so sharp and only thinks of society. He is our Gandhi. Whenever he would come here, he would ask us to focus on educating our children.”

Yangchen, basking in the cold desert sun, chopping baby carrots, also remembers Wangchuk’s childhood days. “He would run through these streets playing, laughing all day long. We all knew he was not like the rest of us.”

Standing beside her, another neighbour, Konchok Zangmo, says, “We have stopped watching television. It angers us, all this fake news about him. That man doesn’t even own a property in his own village.”

Even today, villagers say Wangchuk is present not just at festivals like Losar, the Tibetan New Year, but also for every birth and death in Uleytokpo. During Losar, he joins the celebrations, singing in keeping with the community’s traditions.

Whenever he visits, he spends his time with the three brothers. “We are like quadruplets,” the eldest brother said.

In the govt’s crosshairs

As an activist, Wangchuk always wanted to make a difference.

For over three decades, he has been at the forefront of fighting for Ladakh’s sustainable development, ecological protection, political autonomy, educational reforms, and promotion of eco-friendly tourism.

Along the way, he earned several accolades, from the Governor’s Medal for educational reform in Jammu and Kashmir to the Ramon Magsaysay award for his innovations and work.

But he found himself in the government’s crosshairs between 2023 and 2024 after the abrogation of Article 370, when Ladakh was given Union Territory (UT) status without a legislature. This is also when he entered the political demographic of the region.

Earlier, he had urged people to boycott Chinese products after the Galwan clash and even thanked Prime Minister Narendra Modi following the abrogation, calling it a fulfillment of “Ladakh’s longstanding dream” on 5 August 2019.

Since 2023, he has actively criticised several government projects, like a proposed 13-gigawatt project in Chantang and large-scale solar projects in the region. He has also demanded that the region needs protection from industrial and mining lobbies, along with constitutional safeguards under the Sixth Schedule and also criticised tourism expansion.

When the government restricted his movement at Khardung La pass during a fast that year 2024, he reportedly said, “For the last three years, everything has gone astray in Ladakh and the system is a total failure…On Republic Day, my movement was restricted. This is like a banana republic and a dictatorial state.”

Sowing seeds of activism

In his early years, until he was about nine, Wangchuk’s teacher was his mother, Tsering Wangmo, who taught him their native language and culture in their mud house in Uleytokpo.

Then he was sent for around two years to Nubra Valley to stay with a distant relative, Hamid, who took him to school daily and also taught him at home while his brothers were studying in Delhi.

His father, Congressman Sonam Namgyal, a minister in the Jammu and Kashmir government, married his mother in his second marriage. The family has nine children—six brothers and three sisters—some living in Leh. Others are in other parts of India and one sister is outside in Singapore.

His father had moved to Uleytokpo from Sakti village and his mother had started farming there. The parents kept busy—one in politics and the other building their home here.

Wangchuk later moved to study in Delhi’s Vishesh Kendra Vidyalaya, where he joined his brothers in boarding school.

After graduating from NIT in 1987, Wangchuk returned to his village and co-founded the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) in 1988 with the help of his brother, Sonam Dorjay.

Today, the NGO wing behind SECMOL finds itself in the midst of a Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 2010 (FCRA) controversy as the MHA alleges it violated foreign funding guidelines multiple times.

Wangchuk had earlier said the government was building a case aimed at putting him behind bars.

Running completely on solar energy, SECMOL gives foundation courses to those who have failed Class 10, as well as to those who want to take a gap year. The school offers counselling classes to teenagers, with some of them going on to work there.

With the start of SECMOL, Wangchuk moved out of his village and started working on mobilising the people of Ladakh to educate their children. This experience then went on to become the inspiration behind Aamir Khan’s 3 Idiots and its main character, Phunsukh Wangdoo.

“He was always upset with the education system. It concerned him that the children of Ladakh were behind in education. He believed in an education system for all; he always argued that there had to be a way to make it inclusive,” said Sonam Dorjay.

It was at SECMOL that Wangchuk met his first wife, an American citizen, Rebecca Norman, who had come to volunteer at his institute, but the marriage ended in divorce. He later married Dr Gitanjali J. Angmo.

Later, Wangchuk went on to help launch ‘Operation New Hope’ to reform the government education system, forging ties with the Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir administration in 1994. By 2005, he became a member of the National Governing Council for Elementary Education under the HRD Ministry.

Spalzes Angmo, a 36-year-old grocery shop owner, fondly remembers her days at SECMOL. “I had first joined the SECMOL in its summer camp for 15 days in 2008 and then gone for the foundation course in 2015-2016 after my Class 10. I not only learnt English but also how to be more self-confident and responsible. I also learnt life skills, such as how to use solar energy and cultivate vegetables in the harsh climate here. The best part, I learnt ice skating.”

She too had volunteered in SECMOL and later also worked as a tour guide but business halted when Covid hit. “A 40‑year‑old man, who once worked as a waiter at Wangchuk’s eldest brother’s resort, recalled how the activist would drive from village to village in his jeep, spreading awareness about education.”

Apart from education, Wangchuk has also been at the forefront of saving Ladakh’s fragile ecosystem.

Recalling Wangchuk’s turn to environmental activism over Ladakh’s fragile ecology, Dorjay said, “When we returned from our studies, the water was no longer clean, the climate was changing. We talked about it, but Sonam acted.”

In 2013, as climate change led to a melting of Ladakh’s glaciers, he devised an artificial glacier, or an Ice Stupa, to store winter meltwater for use in the growing season.

Though it was widely celebrated, the project recently faced skepticism and complaints from local villagers in Phey who accused it of contributing to plastic pollution.

Earlier, in 2011, Wangchuk went to study Earthen Architecture at the CRAterre School of Architecture in France for two years. In 2018, Wangchuk founded the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives, Ladakh (HIAL), along with his wife, Angmo.

Both SECMOL and HIAL showcase green campuses with passive solar‑heated buildings and other sustainable technologies, including solar pressure cookers and solar water heaters. In the past, Wangchuk’s HIAL has also developed solar-heated tents for the Indian army in 2021.

A day before his arrest, the home ministry cancelled the FCRA licence for SECMOL alleging violations such as receiving funds from a Swedish platform to conduct a study on “sovereignty of the nation”.

Angmo told ThePrint the home ministry had “frivolously misinterpreted” funds meant for food sovereignty as meant for a “study on sovereignty of the nation”.

HIAL is also currently under scrutiny, as the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) is investigating alleged FCRA violations over allegedly receiving foreign funding without a license. Last month, the Ladakh administration cancelled HIAL’s land lease, citing failure to formalise the agreement and lack of progress on the project.

The Centre has also alleged that Sheshyon Innovation, a private company in which both Wangchuk and Angmo are directors, was used to divert funds.

Moreover, it has accused HIAL of giving degrees without being a recognised university.

However, Angmo says that while their UGC recognition is pending, a private institute doesn’t need to have UGC recognition. HIAL offers 11-month fellowships as well as 3-6 months short-term certificate courses.

She and Wangchuk’s supporters say he’s a victim of “witchhunting”, but the government calls it an “action based on evidence and credible inputs”.

Angmo also said that Wangchuk “wants development, not rampage”.

“They have picked everything out of context and are trying to defame Sonam Wangchuk. The whole world has seen that he is a Gandhian; he isn’t a threat to the public but is a celebrated hero,” Angmo told ThePrint in an interview.

Dissent to jail

Wangchuk may not have joined active politics like his father, but his activism was inspired by him. In the 1980s, Sonam Namgyal went on hunger strikes demanding Scheduled Tribe status for Ladakhis, drawing the attention of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who flew in and offered him a glass of juice to break his fast.

Over the years, Wangchuk followed in his footsteps and has been on several hunger strikes to demand protection for the environment and constitutional safeguards for the people of Ladakh.

In his latest hunger strike, cut short by violence, Wangchuk was joined by his eldest brother. “We don’t join all his protests; people will think the whole family has a hidden agenda,” said Sonam Dorjay, his third brother.

Local residents here also recall that Wangchuk didn’t just work for Ladakh broadly—he supported people at the smallest, everyday levels.

Konchok Zangmo’s elder daughter, 28‑year‑old Tsewang Dolma, joined the hunger strike on 24 September after youth apex body leaders urged participation. The family credits Wangchuk not only for career guidance but also for financial support.

After her Class 12, the younger daughter, 25‑year‑old Thupstan Dolker, along with her mother, approached Wangchuk for career advice, her first close interaction with Wangchuk.

He offered to fund her Common Law Admission Test coaching, though she declined, fearing she might not clear it. “I didn’t want to waste the money, so I studied Hindi instead, and he helped both of us,” Dolker said. Both sisters are now postgraduates from Chandigarh University.

As Wangchuk’s fate hangs in the balance, back in Uleytokpo, elderly village women sit under the sun discussing how they had asked Wangchuk to become a “family man”. But he refused, saying he had Ladakh to look after and “can’t get distracted”.

(Edited by Sugita Katyal)

Also Read: ‘Centre disrespected our patience, anger against BJP’—how smolder turned into blaze in Ladakh