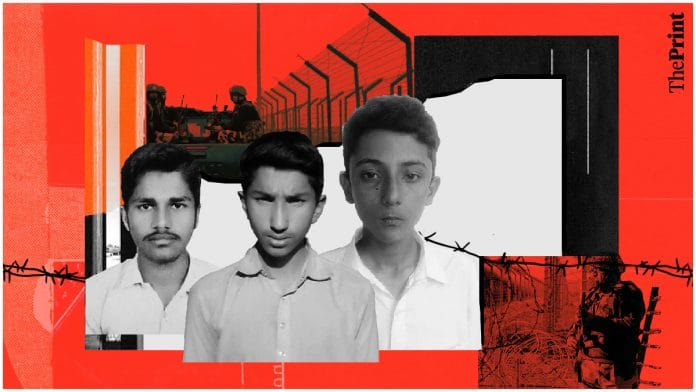

New Delhi: It was in August 2021 that 14-year-old Khayam Maqsood, a Pakistani schoolboy, strayed into the Indian side of the Line of Control (LoC) while “searching for his goats”. Three months later, in November 2021, Asmad Ali, also 14, crossed over into India while “chasing his pet pigeons”. Two years before, Ahsan Anwar, then 16, had crossed over into India while playing “hide and seek” with his friends in October 2019.

All three juveniles were detained by the Army, handed over to the Jammu and Kashmir Police, and eventually landed up in the Ranbir Singh Pura observation home in J&K’s Poonch.

They underwent a trial and the Juvenile Justice Board, Poonch, ordered their release between 2021 and 2022, after it was proved that they crossed over to the Indian side “unintentionally”.

But despite orders for their release having been issued more than a year ago — nearly two in one case — the boys are still lodged in the observation home. While the order to release Anwar came on 30 June 2021, those for Maqsood and Asmad came on 25 August 2022. ThePrint has accessed all the three orders.

Among the three cases, while Maqsood was acquitted of all charges, Ali and Anwar were pronounced guilty of crossing into India without proper permission. A resident of Nankana Sahib in Pakistan’s Punjab, Anwar is now an adult.

Rahul Kapoor, a human rights activist closely involved in all three cases, told ThePrint that despite court orders to release them, and Pakistan seeking their repatriation, the process to send the boys back is yet to begin.

“The CID has given the teens a clearance, the jail superintendent has also submitted a report, but the teens are still stuck,” Kapoor said.

He added that Anwar has been here for almost two years, which means he has already served the minimum sentence awarded under the Foreigners Act.

“The other two children have also been stuck for more than a year,” he said.

According to Kapoor, he has raised the issue of the children’s release on humanitarian grounds with the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), and the foreign office at Pakistan and the Indian High Commission, but has yet to receive a response.

“The family of the juveniles met the officials of Pakistan Foreign Office requesting their release. They (officials) conveyed the request to the Pakistan High Commission in India. Following this, the high commission verified the credentials of the juveniles and conveyed to its Indian counterpart that the children are Pakistan residents and must be sent back home. Despite this verification report, their release could not be secured,” he said.

“It is even more disheartening because the children are losing crucial years of their life, being stuck in an observation home despite getting all clearances. The court has ordered their release, but it is still being delayed on one pretext or the other,” he added.

Though Ali was allowed to speak to his family members on the phone once, similar requests by the other two have been denied, claimed Kapoor.

ThePrint reached MEA spokesperson Arindam Bagchi via call for a response on what is leading to the delay but had not received a response by the time of publishing this report. This article will be updated when a response is received.

‘Don’t know when we will see our child’

For the families of these Pakistani teens, the delay has shattered whatever hope they felt after the release orders were issued.

Speaking to ThePrint over the phone, Ali’s uncle Arbab Ali said that he had done whatever he could to ensure his nephew’s return, but felt extremely helpless. Ali’s mother, he said, passed away when the boy was an infant, after which his father abandoned him. Arbab Ali and his family then took Ali in and raised him.

Ali belongs to the border village of Tatrinote in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK), which is merely 20-30 steps from the LoC.

“He went missing in November 2021 and we had no idea he had crossed over to the Indian side while running after his pigeons. We got to know through social media that he had been arrested in India. He is a child and had no idea that it is a separate country and that he will get stuck. Since that day, we have been trying to bring him back home,” he said.

The boy’s uncle added that he had visited the Pakistan Foreign Office many times since, but was told each time that they had sent a communication to their Indian counterpart, and “nothing has moved in the last year-and-a-half”.

“It is a long wait, we do not know when we will be able to see our child.”

The orders for Asmad Ali’s release convey a similar story. According to the orders, he claimed that he crossed over into J&K without realising that he was entering another country’s territory.

Moreover, nothing suspicious was recovered from him. But since he was guilty of crossing into India without proper permission, Ali was booked for committing an offence under Sections 2 and 3 of The Egress and Internal Movement (Control) Ordinance, 2005.

Although the allegations against him were proved, the court ordered his release, since he is a juvenile.

“He is convicted but, being a juvenile, he cannot be sentenced under the law. So, he is ordered to be released subject to furnishing of an undertaking duly attested by the magistrate that he shall not repeat the offence,” read the order.

Kapoor, who took up Ali’s case and started a campaign for his release, said that though he was convicted, being a juvenile, he was not to serve any prison sentence. He should have been allowed to leave after providing an undertaking that he would not repeat this offence, he said.

‘Have been running from pillar to post’

Khayam Maqsood’s story is no different.

His elder brother Ahtisham, who works as a sales executive with a clothing brand in Islamabad, said their requests and appeals have not borne any fruit in the last two years.

“Almost two years have passed and we have not heard from our younger brother even once. We do not know how he is and in what condition. His only fault was that he crossed over into India by mistake,” he said.

Ahtisham added that after the family found out why the boy had been arrested, they went to the Pakistan Foreign Office and asked them to send a request to India. “They kept telling us that the request is pending. We even pleaded with them to at least make us speak to him once, but nothing moved. Now, we do not even know if we will ever be able to reunite with our brother. I feel totally helpless,” he told ThePrint.

For Maqsood, the prosecution made its final submission on 5 July 2022.

In his statement, the boy said he crossed the LoC while running and searching for his goats, and it was only when the Army arrested him that he discovered that he was in another territory.

According to his release order, allegations against him could not be proved and he was acquitted of all charges.

“He did not know the LoC, nor was there any officer to stop him from crossing over. He crossed over to other territory because there was no fencing. He is a juvenile and is completely innocent. Moreover, he is a student and his education has suffered for more than a year now,” Kapoor said.

Anwar, who has spent almost two years in the observation home, shares a similar fate.

“We came across Anwar’s case while working on Asmad’s release. He was convicted but his release was ordered in June 2021. Despite that, he is still inside. It has been almost two years since we have been working to convince authorities,” Kapoor said. “I have been in regular touch with his family back in Pakistan and they are extremely helpless.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)