Pauri/Ramnagar/New Delhi: For 40-year-old Lakshmi Devi, her dressing corner in her one-bedroom house in Uttarakhand’s Jiwai village was her safe space. It was not elaborate — only a 12-inch mirror and a plastic stand for her makeup and jewellery. But every time she stood before it, she always felt beautiful and empowered. She now actively avoids it.

Lakshmi is just one of the dozens of women from Uttarakhand who have become victims of animal attacks in recent years. According to state forest department records, attacks by bears, tigers and leopards have risen at an alarming rate over the last five years. And women, as a primary bridge between their families and the forest, have been at the centre of it.

On 17 November, Lakshmi had gone on her routine run to the forest with her sister-in-law and mother-in-law to gather fodder for their cows.

While cutting grass, she was attacked by a bear. The last thing that Lakshmi remembers is a towering figure consuming her, and within seconds, she was writhing in pain, blood gushing off her face and head.

Her screams echoed through the quaint village. And life as she knew it changed forever.

“I still have nightmares from that day,” Lakshmi said. “I wake up covered in sweat. I try to joke around during the day to forget the memories, but I know that my life will never be the same again.” She now has a trail of stitches on her forehead where her bindi once rested.

Her kohl-rimmed eyes are now partially gouged out.

Uttarakhand forest department data show that in 2025, there were nearly 71 bear attacks in the state that led to at least six deaths. Twelve people died of tiger attacks. And, nearly 80 per cent of these victims are women, according to state estimates.

Environmentalists and forest officials said the primary reasons for the uptick in these attacks are shrinking forest cover, warmer winters, and the unusual trend of disrupted hibernation and animal movements. As a result, women, who routinely venture into the forests to fetch water, firewood and fodder for their cattle, become the victims.

“We try to quantify the impacts of climate change through temperature and rainfall data, but these incidents (of animal attacks) are also the side effects of it. Residents have been paying the price, and it is only likely to get worse in the coming years,” said RK Mishra, principal chief conservator of forests (wildlife), Uttarakhand Forest Department.

Also Read: Why it took 30 years to declare Delhi’s Southern Ridge a reserved forest

Lives changed

Shankari Devi spends all her days sitting on the floor, on a thin mat spread outside her house in Pauri’s Banegh village. There was a time when she would run around finishing household chores, tending to her goats, and catching up with her friends in the neighbourhood.

But now her days are spent in silence, staring at the distant forest where she was ripped apart. On 23 November, Shankari — who had also ventured for her daily fodder run to the forest — was attacked from behind by a bear.

She was told she was lucky to escape the animal’s clutches alive, but she is now left with serious injuries to her right leg, from her calf and thigh, to her privates. She barely managed to crawl to the end of the forest bounds, her salwar soaked in blood, screaming for help before losing consciousness.

“I have around 80 stitches. Every movement hurts, but at least I am alive,” Shankari whispered.

But the impact of the attack goes beyond physical wounds.

“She rarely speaks now. She needs assistance with standing, sitting, lying down, and even going to the bathroom. But it’s her silence that is the most haunting,” said Shankari’s neighbour, Shanti Devi.

But Shanti Devi has decided not to give up on her friend. Since the accident, she, along with other women in the neighbourhood, comes over to Shankari’s house every day at 11 am to cheer her up. Most of the time, Shankari is silent, but now and then, she smiles.

The women take that as a win.

But in nearby Ramnagar’s Ringora, 51-year-old Tulsi Devi was not as lucky.

In November 2024, she had gone to fetch water about a kilometre away from her home when a tiger lunged at her. The animal mauled her by the neck before dragging her into the forest, where her half-eaten body was found the next day.

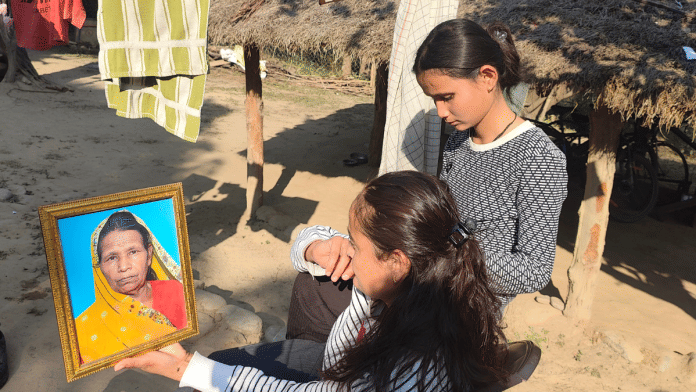

Tulsi’s 17-year-old granddaughter, Tanuja Kadakoti, shivers every time she has to recount the story of the fateful evening. She was only three when she lost her mother, and her grandmother had stepped in to raise her. For Tulsi, her siblings, and her cousins, the matriarch was their only family.

Now, she feels like an orphan.

“Dadi (grandmother) brought us all up like a mother. None of us thought that she would go to the forest that day and never return,” Tanuja said, clutching on to a framed photograph of her grandmother.

Also Read: Life in the shadow of Kashmir human-bear conflict, where dense forests meet human action

Growing attacks

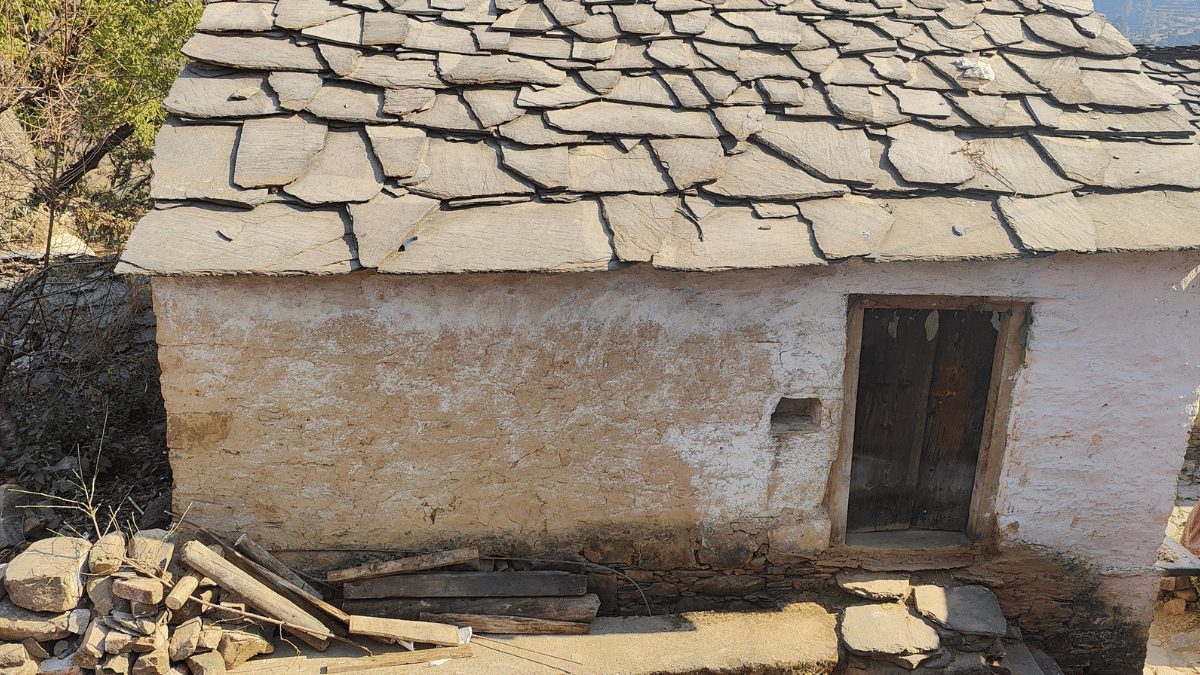

In December, the roads leading to Bironkhal in the mighty peaks of the Pauri Garhwal district should have been wet with morning dew. The air should have been heavy with fog, and residents should have been wrapped in layers of woollens to stay warm against the biting cold.

But these idyllic scenes, which were the identity of Uttarakhand’s mountains, are a thing of the past. The roads are brightly lit by the scorching sun, the temperatures are above normal, and people are out in their summer wear, uncomfortable in the heat.

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) data shows that in Bironkhal, one of Uttarakhand’s bear attack hotspots, the maximum temperatures in the first fortnight of December have remained between 22 degrees Celsius and 18 degrees Celsius—at least 3-4 degrees above the season’s usual temperature.

It is not just the temperatures. There is also an anomaly in the rainfall patterns in the state.

In November 2024, according to the Uttarakhand Meteorological Centre (UMC), the state recorded only 0.1 mm of rainfall, nearly 98 per cent below the month’s average.

“Since we did not get rain or snow so far this winter, the temperatures rose drastically,” said CS Tomar, director of the UMC.

Meteorologists and environmentalists say that such consistent extreme weather recordings have bigger implications.

For instance, animals like the Indian Himalayan bears, found in large numbers in forests across Uttarakhand, usually begin their winter hibernation around October, when the temperatures start to fall. But now, due to warmer temperatures, the hibernation period of these animals has shrunk significantly.

Consequently, they are becoming more aggressive, roaming the forests and often wandering into human settlements in search of food.

Mohan Pargaien, a former Indian Forest Service (IFS) officer, said that for bears, the easy availability of garbage, unattended fruit orchards and crops like maize and millet becomes an easy lure. This results in more gruesome attacks.

“As most men in these pockets migrate for work, women managing the households become the victims of these attacks while collecting grass or wood in the nearby forests,” Pargaien said.

In a post on X, he stressed the need for strong, implementable strategies to control such attacks.

“The women of the hill states, especially Uttarakhand, who have been instrumental in the conservation of forests and wildlife, are now suffering the most from the worsening crisis of human-wildlife conflict, mostly from increasing bear attacks,” Pargaien said in his post, adding that nearly 140 people were injured over the last two years in the state from these attacks.

In the case of tiger attacks, things become more complicated. Unlike bear attacks, there is very little possibility for a victim of a tiger attack to survive.

Senior officials from the Ramnagar forest department told ThePrint that an increasing tiger population in the Corbett National Park is one of the primary reasons behind these attacks.

According to the last tiger census in 2022, the park, which covers Nainital, Almore and Pauri districts, is home to 266 tigers. A sharp increase from 215 tigers in 2017. The park’s official website also highlights that it has the highest tiger density among India’s 50 tiger reserves, with 14 tigers per 100 square kilometres.

But as the number of tigers increases, so do the attacks.

“When the tiger count increases, there are problems of territory and a shortage of prey. Villagers venture into forests for their daily needs, but tigers prey on them and attack,” an official from the Ramnagar forest department said.

Last year, three people died in the Ramnagar division alone from tiger attacks, forest department data shows. These cases were reported from Ringora, Kyari and Okhaldhunga — all heavily populated villages. In 2023 and 2022, five people each lost their lives to tiger attacks and in 2021, four people died.

Also Read: India’s tiger population likely to jump by 10% in new census. ‘But, running out of space’

Dependence on the forest

When Tulsi Devi’s body was recovered from the forest last year, family members and villagers blocked the roads leading to the village in anger. They demanded that the forest and state authorities provide facilities such as water and electricity to the villages so that local women do not have to depend on the forest.

As a peace offering to the protestors, the forest department installed a water tank closer to their village so that women no longer had to venture deep into the forest to fetch water.

Since June 2025, the forest department has also been conducting quarterly meetings with villagers to raise awareness about tiger hotspots and discuss ways to keep them out of the forests.

Even though the recent attacks have instilled fear among the residents, they have little choice but to enter the forest. The residents rely on wood for cooking and fires to keep their homes warm during the harsh winter months. It is also where they take their cattle for grazing.

After the villagers voiced their concern, the forest department agreed to meet them halfway. Instead of completely banning entry as suggested in January 2025, the department in June decided to allow villagers to enter through limited gates, only in large groups.

“That is not a solution. You can allow big resorts to be constructed and their tourist guests to be inside the forests without checks, but you are restricting the poor,” Urmila Rawat, a 38-year-old neighbour of Tulsi Devi, said.

Other villagers agreed.

Many, in fact, believe that the growing number of tourists in the area is causing tigers to move away from tourist zones and closer to residential colonies.

According to the Corbett National Park estimates maintained by the forest department, park receives between 3 and 3.50 lakh tourists every year.

“This was a serene town before it was raided by tourists. The forest department, resort and jipsy owners and operators have turned it into a business,” said SK Negi, a retired schoolteacher from Kyari, where a 62-year-old man was killed by a tiger last year.

“They can keep saying that the number of animals has increased or that they have become more aggressive, or even that villagers are getting into forests. But the truth remains that their greed has brought this situation.”

Also Read: Himachal farmers are ditching apples for persimmons. ‘Earnings on par with JEE packages’

New beginnings

In Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital, Lakshmi Devi is fighting to own her identity. On 18 November, she underwent her third surgery at the hospital. Before this, she had also undergone a face reconstruction and vision recovery surgeries.

The latest one is an attempt to recover her face as close to her original self as possible.

When she was attacked, the doctors near her hometown gave up on her. They said that Lakshmi had lost her vision fully, and the gashes to her face, head and body were so deep that she would always be dependent on someone for her routine.

Even now, she wakes up drenched in cold sweats from nightmares of the day of the attack. Scenes of the bear’s bloodshot eyes scanning her with hunger and pointy claws slashing through her face come running back.

But she is determined not to surrender; with her family at her back, she is ready to face the journey ahead, no matter the high costs of treatment and medication.

Her husband, two children, and her brother-in-law have rented a house in south Delhi’s Kishangarh, where they are staying till her treatment is completed.

“We will do everything in our capacity to help her get her life back,” said Jaipal Singh Negi, Lakshmi’s brother-in-law.

Lakshmi agrees she has a long way to go. Mustering the courage to look in the mirror might still take time, but she has started applying a bindi, even if it is on her broken and stitched-up forehead.

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)