New Delhi: The ground around the launch sites of Chandrayaan-3 and Aditya-L1 missions is eroding. And the climate countdown for Sriharikota has begun.

About 80 kilometres north of Chennai on the eastern coast, this small mass of land in Andhra Pradesh is a realm where Earth’s terrestrial boundaries blur into the expanse of the cosmos. Resting in the Bay of Bengal, the island, with its storied reputation, continues to bask in national pride after this year’s successful launches of the Chandrayaan-3 lunar and Aditya-L1 solar missions.

However, even as India looks forward to future launches of its first human spaceflight Gaganyaan and Venus orbiter Shukrayaan, attention is slowly turning to a major impediment to launching future missions — coastal erosion at Sriharikota.

Its journey from confidence to climate crisis, pride to panic, is bubbling up in public conversations. Along with it comes the heavy realisation that scientists may now have to zero in on a new launchpad for India’s space ambitions.

ISRO’s spaceport island reportedly lost over 100 meters of shoreline in the last four years, coupled with the loss of two major roads to cyclonic storms. In early 2022, concerned officials at the Satish Dhawan Space Centre (SDSC) in Sriharikota enlisted scientists from the National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR) to conduct a study and propose solutions to the sea erosion threat.

Sriharikota’s rich history and legacy in Indian nation-building are unparalleled. If the scientists have to move on to another site, it will be a loss of both tangible and intangible national memory.

Earlier this year, the NCCR team submitted a report outlining the causes and effects of erosion. While the findings have not been public, NCCR officials acknowledged the erosion threat, attributing its worsening to human activities like dam construction and port development.

Now, they are waiting for the central government to approve the proposed remedial measures, including building groynes, limiting construction activities, and replenishing the depleting coastline with fresh sand.

“Any environmental management plan should be scientifically sound,” said MV Ramana Murthy, director of NCCR. “It is very important to remember that we are anticipating an increased number of extreme weather events in the future. All of our planning and future construction projects need to consider these extremes when it comes to preparing ourselves.”

The sands of Sriharikota have not just witnessed thundering rocket launches but also the stories of the Indian scientists and engineers who’ve challenged the limits of the sky.

Also Read: A Tamil Nadu village and its precious soil put Chandrayaan-3 on the moon. Now, farmers are scared

Finding Sriharikota

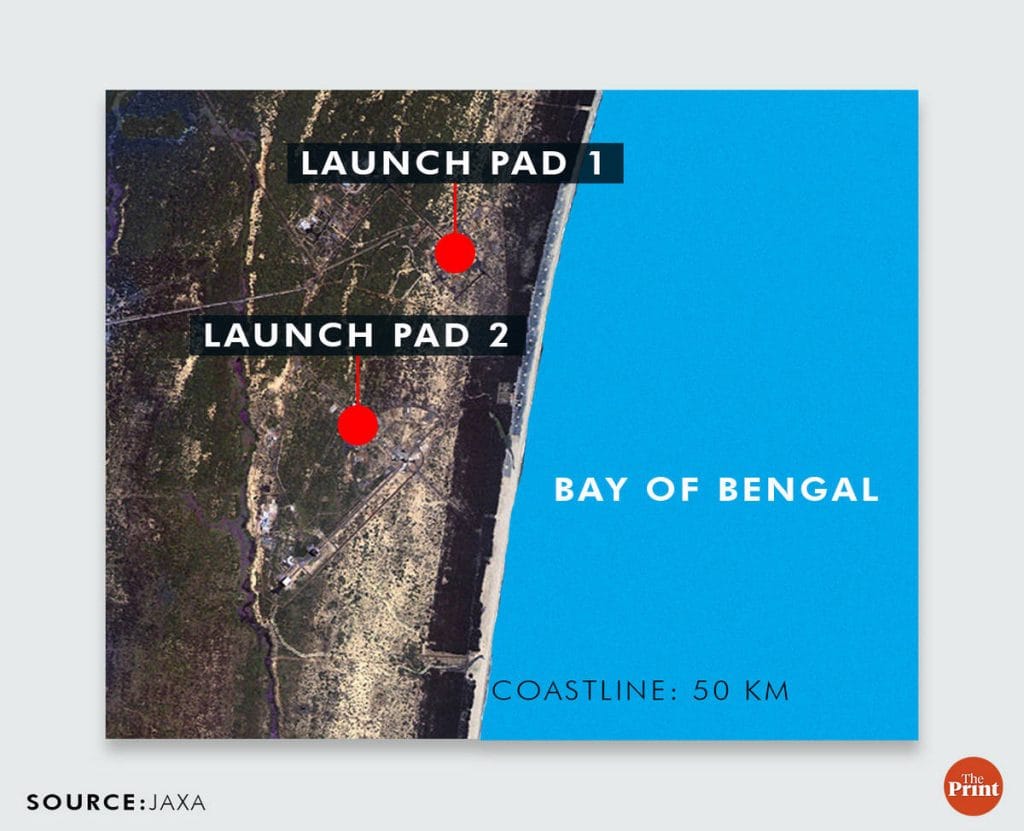

Sriharikota, off the coast of Andhra Pradesh, is the epicentre of India’s forays into the final frontier. It is home to two launchpads where ISRO propels spacecraft— and if all goes to plan, humans— into the cosmos.

Covering an area of 175 km with a 50 km coastline, it is separated from the mainland by the Bay of Bengal on one side, and the ecologically sensitive Pulicat Lake, a bird sanctuary, on the other.

A single road cuts through the Pulicat Lake—the second largest brackish water lagoon in India—leading to the island. Approaching Sriharikota, the surroundings transform into a thriving ecosystem of mangrove forests, inviting flocks of migratory birds. For humans, however, entry is highly restricted.

In contrast to the natural green sentinels that welcome birds from all over the world, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel conduct thorough checks of anyone entering the island.

The Union minister of science, Jitendra Singh, often repeats this line in public events: “Earlier, you either had to be a very accomplished scientist or become a publicly elected minister like myself to be able to visit the island.”

Up until 1968, Sriharikota was nothing more than a secluded island with sprawling reserved forests, says Pramod Kale, former director of the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC). All it had back then was a canal built for drought relief and an under-construction road across the lake to Sudurpeta to help transport fuel wood to Chennai.

However, it had certain features that grabbed the attention of space scientists searching for the perfect rocket launch site.

First, it is close to the equator, which means rocket launches get a boost from Earth’s rotational speed, allowing for heavier payloads and better fuel efficiency.

Second, it is far from human settlements and surrounded by an expanse of water, making it a safe location in case a launch goes awry.

And the third reason is its solid ground. The island’s firm soil and layer of hard rock underneath it are optimal for handling the powerful vibrations caused by launches.

Sriharikota has so far witnessed 76 successful launches out of 91, including the three Chandrayaan missions, Mangalyaan, Aditya L1, and even India’s first private rocket launch by Skyroot.

In early 1968, Kale and his team undertook an expedition to the island after having conducted a feasibility study of the area that relied on maps.

“Dr Sarabhai asked us to look at Sriharikota as a potential location. At that time, Dr Abir Hussain who was the director of industries with Andhra Pradesh government helped us arrange visits to the area,” Kale told ThePrint.

The team went halfway on a jeep and then had to reach the island by boat.

Until that time, Kale had only studied the island on maps. What he wanted to assess was the coastline.

“I wanted to see the tide early in the morning as it came in and see how the coastline actually looks,” he said.

However, back then there were no roads, and trudging the span of the island on foot was a tough prospect for the scientists.

(Sriharikota) is still one of the most important centres. Not only do we launch our main rockets from there, we also have a propellant plant there

-Pramod Kale, former director of the Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC)

“There was a trolley, pushed by people, which was used to cross the island to get to the coast. For that, I had to stay overnight. We started about two in the morning and reached the coast just before sunrise,” Kale said.

That first impression the sunrise made on Kale created history. With photographs of the pristine coast, Kale went back to ISRO with positive feedback.

However, before finalising the location, Vikram Sarabhai wanted to survey the island. “At the time, The Hindu had a small Dakota plane that we rented. We visited several areas by air — Kalpakkam, Mahabalipuram — and then this location was selected,” Kale recalled.

The making of India’s space hub

Sriharikota was chosen as India’s satellite launching station in 1969, but it took a little while longer for it to become the powerhouse it is known as today.

The Sriharikota Range (SHAR) launch site became fully operational in 1971 with the launch of the RH-125 sounding rocket. However, the first attempted orbital launch, of the satellite Rohini 1A aboard a Satellite Launch Vehicle, ended in failure on 10 August 1979.

Despite this early setback, Sriharikota has so far witnessed 76 successful launches out of 91, including the three Chandrayaan missions, Mangalyaan, Aditya L1, and even India’s first private rocket launch by Skyroot.

The launch site was renamed as the Satish Dhawan Space Centre, or SDSC-SHAR, on 5 September 2002, in memory of former ISRO chairperson Satish Dhawan.

Over the years, the island also transformed. From a single road, it now boasts a network of over 200 kilometres of roads, Kale said.

But infrastructural growth also brought new challenges, something that became evident decades ago. Kale said that that the Andhra Pradesh cyclone of 1977, which killed at least 10,000 people, was a lesson also on the island’s vulnerabilities.

“The cyclone (showed) that the road that was constructed from Sulurpeta did not have enough openings for the water to flow in and out properly,” Kale said. Subsequent cyclones have also damaged road infrastructure around the SDSC.

It was not until 2019 that the island opened up to the public on launch days. Even so, very few have seen the launch pads in person.

If you are lucky enough to get a seat in the public gallery on one of ISRO’s launch days, all you see is a skyline of green foliage. The air trembles with anticipation as loudspeakers crackle out the countdown to launch. And then, the ground quivers as a pillar of fire and smoke pierce through the sky. The ear-splitting roar of the rocket is met with cheers from the crowd.

The narrow strip of land that is Sriharikota stands steadfast in the face of these ground-shaking launches. However, there are other quieter forces at play too. The island weathers the forces of nature on either side, as waves crash on its coastline, slowly but surely eroding its shores.

Recipe for erosion— roads, dams, ports

When ISRO first surveyed the island, there were already some signs of erosion, but nothing that was not manageable with the right precautions, Kale said.

Preserving the island’s forest cover was always a cornerstone of Sriharikota’s development plan, he explained. “Both Vikram Sarabhai and Homi Bhabha were deeply concerned about environmental protection.”

According to him, the coastline is susceptible to erosion, and construction activities even 20 kilometres away from the island have an impact.

“We had a similar experience in Thumba also,” Kale said, referring to the rocket launching station in coastal Kerala.

Coastal construction contributes a certain percentage of loss of water and sediment, but the main reason is dams

-Ramana Murthy, director, National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR)

Coastal erosion, a natural process shaped by the interplay of water and sediment, is accelerated by human activity and the effects of climate change. The flow of water is dependent on the presence and quantity of sediment, which can temper the waves and contain them.

NCCR director Ramana Murthy explained that extreme weather events and rising sea levels expedite erosion. A rise in sea level pushes more water towards the coast, chipping away at it more rapidly.

The coastline of Sriharikota interacts with two water sources—the Pulicat Lake and the silted river mouth at the Rayadaruvu inlet to the north.

The freshwater from the rivers mix into the sea water here, dredging up sand and sediment.

However, the construction of dams on the rivers feeding the lake— the Araniyar and Kusasthalaiyars— has reduced both the quantity of water and the amount of sediment that it receives.

“There is a reduction of both freshwater and sand near Sriharikota due to damming upstream,” said Murthy, adding that Pulicat Lake’s volume has reduced by as much as 30 per cent in recent times.

Another human activity that affects the flow of water and sediment is construction along coastlines, especially ports. NCCR’s analysis has shown that both Ennore and Adani Kattupalli ports contribute to impeding the flow of sediment and water, although they are each 50 km south of Sriharikota.

“Coastal construction contributes a certain percentage of loss of water and sediment, but the main reason is dams,” NCCR’s Murthy said.

Since early last year, researchers at NCCR have been studying how these factors contribute to changes in the shoreline, and what mitigation measures could be adopted to strengthen the coast of India’s rocket island.

Groynes, beach nourishment as solutions

To understand the changes along the Sriharikota shoreline, the NCCR team analysed over 30 years of satellite data. The scientists also identified extreme weather events and sea level rise, especially since 2007.

“We collect (data on) seasonal variation in waves approaching the coastline, and variation inter-annually (between years), to help construct a mathematical model that simulates the movement of currents, sediment, and other material,” Murthy said.

The study, therefore, entailed an analysis of both long- and short-term data to estimate the impact of water on Sriharikota’s coast.

The next step was to devise a solution to coastal erosion.

“Based on the orientation of the coast, and the direction and intensity of the waves, we designed and proposed a solution in alignment with the natural structure of the coast — hence the term nature-based solution,” Murthy explained.

The NCCR team’s recommendations aim to “mimic” and restore the coastline’s original structure, taking into account the extensive damage that has already occurred.

The classified report outlines two major ways to lower erosion — a series of short groynes and beach nourishment.

Groynes are a well-known form of coastal flood defence, comprising low-lying structures that extend from the shore and out to the sea like jetties, but shorter. As water swishes powerfully around them, they trap sediment and also temper the intensity of waves, dissipating their energy before they reach the coast.

Beach nourishment involves adding sand to the coast or adjacent to it. Unlike groynes, this is a “soft structural” mitigation that allows sand and silt to move with the waves and prevents sea surges. Coastal nourishment has been successfully implemented in many parts of the world for nearly a century, starting with Coney Island in the US in 1923.

Also Read: Shipping containers as office, 3D printed rocket engine—a Chennai startup is in a space race

‘We have to protect it’

The NCCR delivered its report to the Satish Dhawan Space Centre and the Andhra Pradesh Coastal Zone Management Authority (APCZMA) during a meeting in Vijayawada in August.

Murthy said that the state authority has cleared the plan, but the central government’s approval is awaited to start the implementation.

The proposed solutions, once in place, are expected to endure for the next twenty years.

However, ongoing concerns about warming waters and sea level rise will require occasional revisits to the plans, according to the NCCR. For now, the agency plans to conduct “periodic maintenance” after two decades.

ThePrint has contacted SDSC-SHAR and the Union ministry of environment, forest and climate change (MoEFCC) via email and phone calls. This report will be updated upon receiving a response.

Meanwhile, ISRO already has plans to establish another rocket launchpad in Tamil Nadu’s Kulasekarapattinam. This new spaceport will provide a launch advantage by allowing rockets to fly directly into polar orbit without the need to manoeuvre around Sri Lanka as is the case for launches from Sriharikota.

But the history of Sriharikota is irreplaceable.

“It is still one of the most important centres. Not only do we launch our main rockets from there, we also have a propellant plant there,” Kale said.

“When looking for a rocket launching station, we have to have a location that does not pose any threat to civilian populations in case of an accident. That isolation is perfectly provided by the Pulicat Lake.”

The island’s firm soil and layer of hard rock underneath it are optimal for handling the powerful vibrations caused by launches.

Kale emphasised the importance of safeguarding Sriharikota.

“If erosion is taking place in any area, we have to immediately take steps to protect it,” he said.

After all, the sands of Sriharikota have not just witnessed thundering rocket launches but also the stories of the Indian scientists and engineers who’ve challenged the limits of the sky.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)