Rajkot: The price of silver is soaring. That should have been good news for Gujarat’s oldest and largest silver market. Instead, panic is brewing.

Arvindbhai Limbasiya’s eyes flicker to the wall-mounted television set in his sparse office. On the screen, the price of silver fluctuates around Rs 2.3 lakh per kilogram, marking a close to 30 per cent increase in less than a month.

In a stable market, Limbasiya – a bullion trader – would have welcomed a gradual price rise and the subsequent boost in profits. But in a counter-intuitive development in Gujarat, extreme price volatility has sent ripples of panic through the silver trade over the last few months.

Silver prices jumped nearly 160 per cent in 2025, fuelled by growing demand from AI-linked industries and the metal’s critical conductive role in electric vehicle batteries. In recent months, supply concerns have deepened after China placed silver under its rare-metal export restrictions, while the United States designated it a critical mineral.

The sharp rise in prices has affected the entire silver ecosystem in Rajkot, one of Asia’s largest hubs renowned for its intricate craftsmanship of silver bracelets, earrings and necklaces. Under normal conditions, silver is supplied first and paid for later, with only minor price fluctuations during the credit period. But when prices jump by Rs 30,000 in a single day, the gap between delivery and payment turns into an unbearable risk for manufacturers.

“Since Diwali, both production and sales have stopped – payments are just not coming in,” said Paresh Dhanani, a Congress leader who campaigned in Rajkot in 2024 and has close friends in the jewellery industry. “The figure [reported in the Gujarat Mirror] is very less. In Rajkot itself, the minimum loss is around Rs 10,000 crore.”

Since Diwali, both production and sales have stopped—payments are just not coming in.

— Paresh Dhanani, Congress leader, Rajkot

From Rajkot to Agra to Kolhapur, manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers are reeling, with many delaying payments to suppliers further up the chain. The Gujarat Mirror reported that 44 trading firms have declared insolvency, with the crisis involving an estimated Rs 3,500 crore in settlement differences.

“Business has been destroyed,” said Limbasiya, the secretary of the Silver Gold Bullion Association, Rajkot, speaking at his office on Pedak Road, the city’s silver hub. “A person who was selling 5,000 to 10,000 kilograms a month is now selling only 5 per cent of that.”

The price rise anxiety has been further exacerbated by traders shorting silver, betting that prices would fall. Instead, prices continued to rise, with traders hedging their exposure losing even more money. On 7 January, silver closed at Rs 2.5 lakh per kilogram. Just a month earlier, it was trading at Rs 1.8 lakh.

A person who sold 5,000 to 10,000 kilos a month is now selling just 5 per cent of that.

— Arvindbhai Limbasiya

Volatility freezes Rajkot trade

On the eastern bank of the Aji River, Rajkot’s silver market doesn’t exhibit any visible signs of an impending crisis. Wholesale and retail shops are open. Owners sip chai behind their counters while workers assemble bracelets and necklaces. But in the face of rising prices, business has come to a near standstill.

“You have to understand that this kind of volatility has not been seen in the past 80 years,” said one manufacturer, his voice drawing to a crawl. “In a year, silver prices usually increase by Rs 10,000. But last December, it increased by over Rs 60,000.”

Who will do business when the price is fluctuating so much?

— Arvindbhai Limbasiya, bullion trader, Rajkot

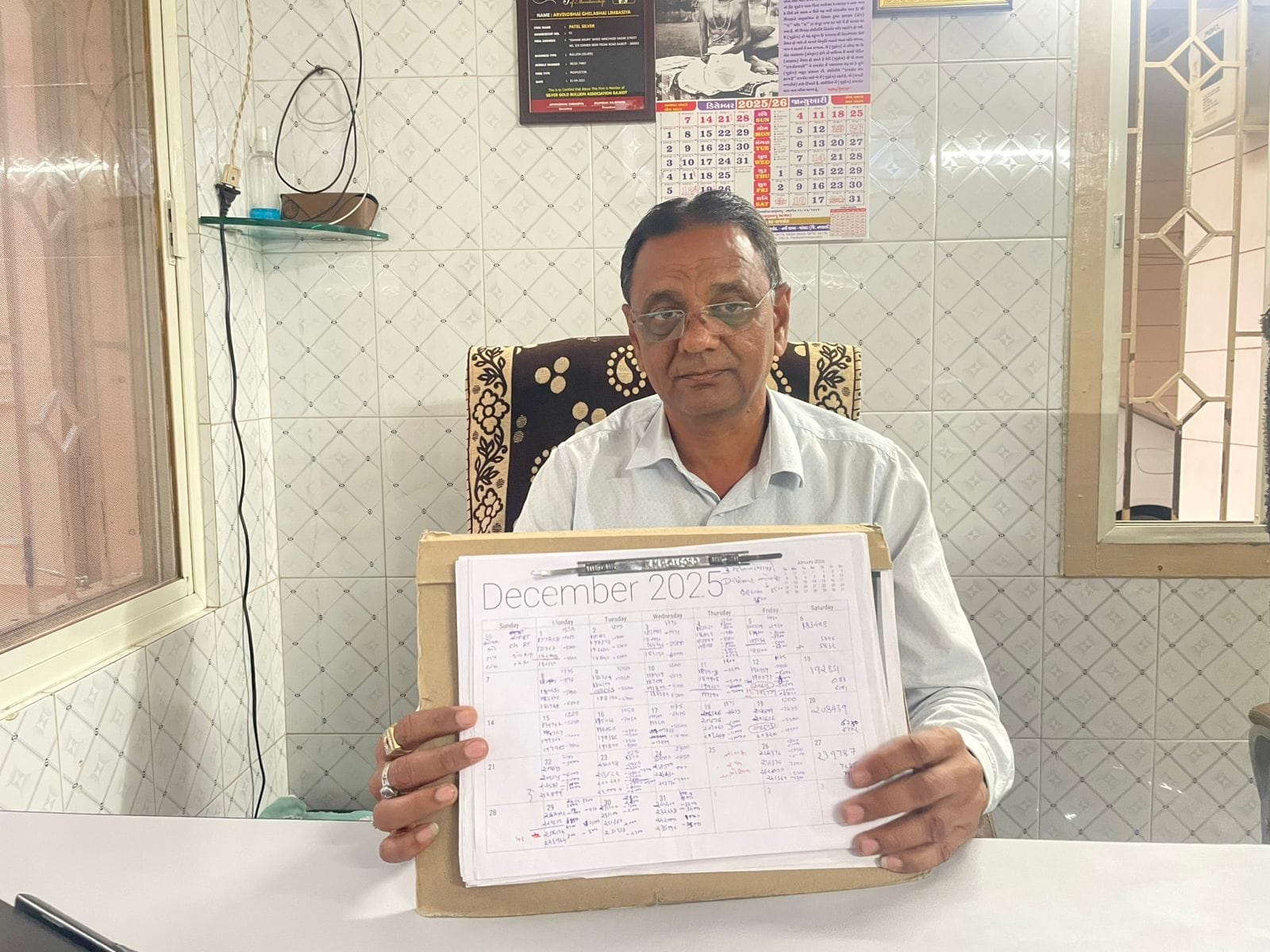

Limbasiya pulls out a cardboard spring file from his desk and flips to December 2025. Each date is filled with scribbled figures showing the daily price movement of silver.

“On the 26th, 29th and 30th of December, all three days had movement of between Rs 25,000 and Rs 30,000,” he said calmly, pointing to the dates. “Who will do business when the price is fluctuating so much?”

He points to entries showing prices nearing Rs 2.5 lakh per kilogram and says he is now afraid to stock silver. “What if you buy at this price and it drops to Rs 2.2 lakh? You will be at a loss immediately.”

Sharp rises and falls can be especially damaging in a business built on trust and long credit cycles. Payment periods can range from a week to a month, more than enough time for volatility to ripple through the entire supply chain.

That chain begins with bullion traders selling pure silver bars, followed by manufacturers who turn those bars into jewellery. Wholesalers then buy the ornaments in bulk and send them to retailers across the country.

One silver manufacturer takes off his ring to explain why price spikes are disastrous. He accepts pure silver from wholesalers, who ask him to convert it into ornaments.

“Say you give me one kilogram of silver to make ornaments, which you sell for Rs 1 lakh,” he said. “Now imagine that the price of that kilogram increases to Rs 1.5 lakh. Since I take payments in silver, the wholesaler must give me back one kilogram — at the higher price. That wholesaler won’t accept a Rs 50,000 loss.”

The whole chain breaks down. Wholesalers stop placing new orders since they are unable to pay manufacturers for old ones. Manufacturers, many of whom take loans for their business, are left sitting on losses.

Limbasiya’s own bullion business has been hit hard. Before Diwali, he sold 50 to 70 kilograms of silver a day. Now, he sells two to three kilograms.

“Sometimes there are no sales for five days,” he said.

Predictably, the price increase has also crushed demand for silver jewellery, which is popular among communities that cannot afford gold.

“A 100-gram anklet that earlier cost Rs 10,000 now costs almost Rs 25,000,” Limbasiya said. “Their budgets are anyway less. Now these pieces have become unaffordable.”

MCX, shorting and losses

Commodity exchanges like MCX (The Multi Commodity Exchange of India Limited) are popular within Rajkot’s silver community. With their ears on the ground and fingers on the pulse of the market, many traders believed they could predict which way the price would swing.

While silver moves physically as bars and jewellery, it is also traded electronically on terminals where it exists as a set of ones and zeros. There is no material ownership of silver, only contracts to buy or sell at a certain price in the future.

People saw small dips and thought it was an opportunity to gamble.

— Silver manufacturer, Rajkot

“When traders, businessmen and manufacturers face losses, their minds start looking for a way out,” said a silver manufacturer who has been in the trade for 25 years. “They see rapid price increases in silver followed by small dips and think it’s an opportunity to engage in satta bazi (betting).”

Traders started shorting silver, betting that prices would fall. For example, if silver was at Rs 2 lakh, they would short it at Rs 1.75 lakh, expecting to pocket the difference once the price fell.

But prices kept rising. And traders holding short positions were forced to pay the difference, widening their losses.

While online trading platforms are legal, despite the market risks associated with shorting, traders in Rajkot also widely engaged in an illegal form of trading called dabba trading. The principles are the same – purchasing contracts on the future price of the commodity.

But dabba trading happens off-the-books, in cash and without any legal guardrails. There is no recognised exchange; brokers take bets inside their own books. Traders circumvent the formal exchange margins, but during periods of high volatility – like in today’s silver market – they stand to lose even more.

“In exchanges like MCX, you use the white money in your bank account. There are also daily settlements, so there are limits to how much you can lose,” said the manufacturer. “But most people here are doing dabba trading, and there is no end to their losses.”

India’s silver hubs feel heat

Rajkot is a manufacturing hub for gold, silver and imitation jewellery. Near Pedak Road, almost every household has at least one family member working in the industry. Some industry leaders see the price rise as an opportunity.

“All the big gold traders are expanding into silver,” said Mayur Adesara, president of the Gems and Jewellery Association of Rajkot. He is sitting in the city’s gold market across the river.

Adesara is optimistic, both of the market and Rajkot’s role in the industry. He spoke proudly of Bollywood stars coming here for jewellery and of the skilled artisans whose dexterous hands put Rajkot on the national map.

To him, there will be casualties, but not on a scale that is disastrous.

However, Rajkot isn’t the only city that deals in silver. Kolhapur is famous for silver utensils, Agra for anklets and bracelets. Major silver hubs also exist in Indore, Varanasi, Mumbai, Hubli, Bengaluru, Coimbatore and Kolkata.

A large silver manufacturer in Kolkata, who often travels to Rajkot for business, said that it is nearly impossible to collect payments at the current rates.

“They [wholesalers] took goods from me at a lower price, so they are dragging their feet, waiting for the price to fall,” he said, frustrated that a price drop isn’t on the horizon. “But they’ve at least made some money selling to retailers. What am I supposed to do?”

One of the manufacturers in Rajkot said that everyone in the industry has money stuck somewhere or the other.

“If silver prices don’t come down in the next two or three months, everything will reveal itself,” he added.

He spread his fingers wide, naming the cities that will be affected by the crisis one by one.

“Rajkot, Agra, Indore, Kolhapur, Varanasi, Mumbai, Coimbatore. When people start demanding their money, that’s when the market will find out who has drowned.”

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)