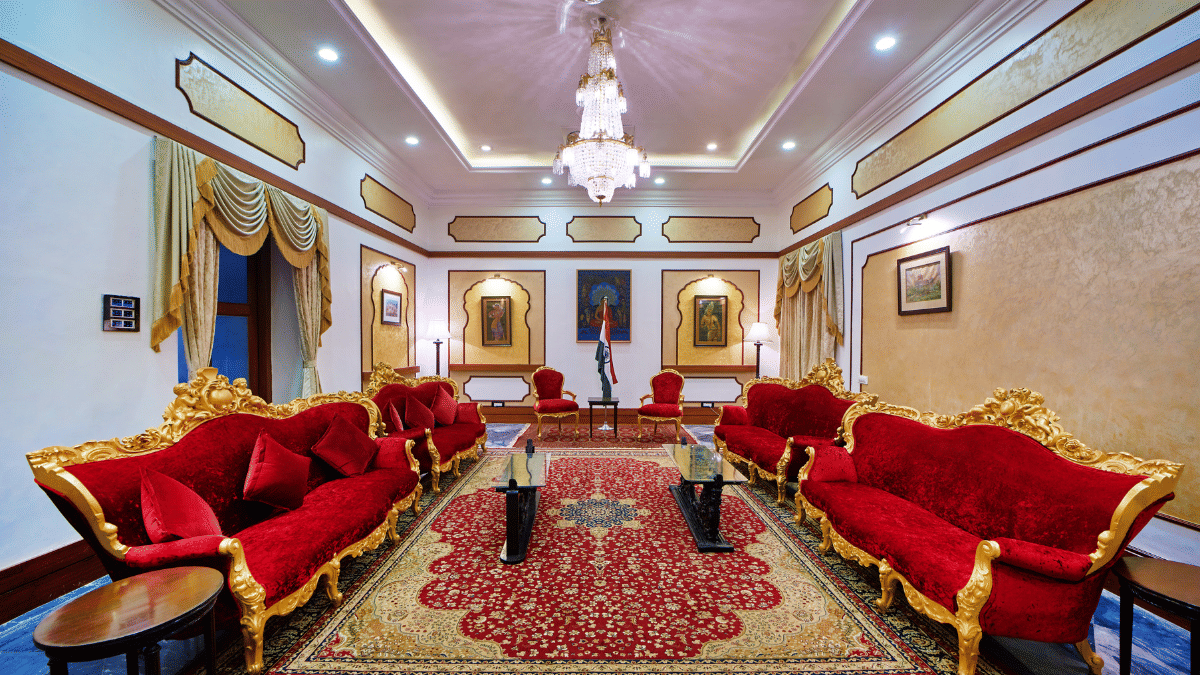

Mumbai: Mumbai’s Raj Bhavan isn’t just any house on a hill. It’s the office of the constitutional head of Maharashtra, a safe house for dignitaries of state, a banquet hall where global leaders like Russian President Vladimir Putin, former German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and six generations of the British royal family have dined. It once held so much power that it was essentially the Buckingham Palace of the East.

It isn’t just a colonial hangover. The country’s Raj Bhavans’ sleepy, old-world calm hides the most important political battles being waged these days in India. Raj Bhavans, the seat of the Governors, are the centres from where the Narendra Modi government exercises control over non-Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) chief ministers — from West Bengal to Tamil Nadu, Punjab to Kerala. Running these are like looking after a white elephant: with a budget worth crores of rupees, huge lawns, ballrooms, banquet halls, tennis courts, medical establishments, swimming pools, dozens of rooms, ADCs at hand, and the occasional sex scandal to snuff out.

The Governors, more than anybody else, are the eyes and ears of PM Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah. And Raj Bhavans are their war rooms.

So, when former comedian and Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Singh Mann accused the Governor of living royally and only using helicopters to travel, he wasn’t joking.

On an August morning, the house at the southernmost tip — reserved for the most important of guests — was reopened for a former inhabitant. An octogenarian ex-Governor needed an eye check-up, and there is no one he trusts more than the Raj Bhavan’s medical staff.

The domestic scene is a far cry from being a relic of the British Raj. The pomp, protocol, and pageantry remain, but the office had to update itself to stay relevant to the Indian public — even if it only means installing centralised AC and replacing British symbols with the Indian emblem.

Former inhabitants and current employees agree on one thing, though: What the office does depends entirely on the person occupying it.

“Raj Bhavan is one of the most dynamic and lively democratic institutions, acting as a strong link between the Centre and the state,” says Umesh Kashikar, the Public Relations Officer of the Maharashtra Raj Bhavan. “The stream of delegations and visitors to the Governor is a testimony of the dynamism and relevance of the institution.”

In Maharashtra, the Malabar Hill house is just one of the four Raj Bhavans. There’s a residence in Mahabaleshwar for the summers, one in Pune for the monsoon, and another in Nagpur. The Arabian Sea wraps around the Malabar Hill Raj Bhavan — including its private beach — and employees are housed either on or outside the premises.

Over the years, the Malabar Hill Raj Bhavan has moulded itself to suit the whims and fancies of past Governors: a tennis court built by one was converted into a Japanese zen garden by another. Recently, a solar power weather station and a fancy new temple were installed. An underground bunker was discovered and turned into a museum open to the public, and British cannons were fished out of the sea and placed in front of the original bungalow. One Governor built a badminton court that was used primarily by their successor and the Raj Bhavan staff, while another Governor built a sunrise gallery to do yoga surrounded by the sea. Another Governor’s favourite peacock has been taxidermied and placed between a ballroom and banquet hall.

“The institution of the Governor’s office is like a moral custodian, even if it does not have executive powers,” says senior political journalist Neerja Chowdhury. “But the time has come for a serious debate on whether the institution is necessary today.”

The crossroads

At a time when de-colonisation is the buzzword in India and politics around the Governor’s office is fraught with federalism, the Raj Bhavan itself has become the site of conflict. The issues can be petty, like getting blocked on X (formerly Twitter) or skipping Independence Day tea parties, or serious like dismissing ministers in state governments.

In just the past year and a half, Governors in non-BJP-ruled states such as West Bengal, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu have made headlines for clashing with their state governments. West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee blocked then-Governor and now-Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar on X after accusing him of using abusive language and making unethical and unconstitutional statements toward her. She went on to say that the Governor treated her elected government as his servants or bonded labourers.

“The Governor’s institution was very different in the past. Today, it’s a slugfest — just look at Tamil Nadu!” says Chowdhury. Calling it a rare exception to the rule, Chowdhury pointed to recent photos of Kerala CM Pinarayi Vijayan visiting Governor Arif Mohammed Khan at the Raj Bhavan on Independence Day 2023. The two have been at loggerheads over several issues, but still put their differences aside for the occasion.

Gubernatorial grabs for power have also triggered fights within state governments. Tamil Nadu Governor RN Ravi has been at loggerheads with the MK Stalin government—from delaying his assent to Bills to dismissing minister Senthil Balaji. In return, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) government accused Raj Bhavan of violating the finance code during the 2023 budget session. Then-finance minister, Palanivel Thiagarajan, slashed the Governor’s discretionary fund by Rs 2 crore.

Other Governors have also gotten into hot water on social media. Tathagata Roy, former Governor of Tripura and Meghalaya known for his communal and hateful tweets, pointed out that though the Governor was described as a constitutional head, the Constitution does not prohibit them from airing their views. Former Maharashtra Governor BS Koshiyari was also criticised for writing an unusually politically charged letter to then-chief minister Uddhav Thackeray, asking him if he had “suddenly turned secular”.

The Raj Bhavan has had its part to play in Karnataka, a state prone to political volatility. In 2010, at the peak of tensions in the BS Yediyurappa-led BJP government, the Congress distanced itself from then-Governor HR Bhardwaj for his “proactive role” in state politics. In 2011, it was Bhardwaj’s nod to two lawyers willing to prosecute Yediyurappa that resulted in the latter becoming the first sitting CM to be jailed for corruption.

But there’s always been drama in the Raj Bhavans. When the Janata Party government came to power in 1977, it dismissed 15 Governors.

“The Governor’s office is increasingly becoming a tool in the hands of the central government — it was so in the past too, but now more than ever,” adds Chowdhury.

The trappings of power

The Governor’s office is a conduit between the Centre and the state — not quite a middleman, nor a catalyst.

As the constitutional head of the state, the Governor has the same symbolic power as the President of the country. And despite not being voted to power, they act as a check and balance to the elected state government.

They’re entitled to many of the same trappings of the presidential officer. Two aides-de-camp, one from the Army and another from the state police, are assigned to the Governor — except in Jammu and Kashmir, where both ADCs are from the Army. The largely customary role offers Army and police personnel a quick route up the ranks. Although, the Army in 2020 reportedly reconsidered its policy of assigning ADCs to the Governor due to a shortage of young officers.

“[The Raj Bhavan] is a relic of the British Raj to the extent that the post was created by the British. The functions and powers of the Governor in the Constitution of India are very different from sweeping powers given to Governors in pre-Independence India,” says Chandrachur Ghose, author of 1947-1957 India: The Birth of a Republic. “Although the Constitution does not delve into the question of necessity of the post, it is clear from the debates in the Constituent Assembly that it was envisaged as an administrative backup.”

This backup involved implementing checks and balances in the provincial governments’ functioning and also emphasising the unitary aspect of the Constitution.

But times have changed. India is no longer a fresh republic that needs an authority figure to keep it in check.

Instead, the Raj Bhavans’ legacy has taken on a different dimension today. Mann’s comments on the royal lifestyle of Governors in India have a lot to do with the Raj Bhavans they live in and the lifestyle they facilitate.

But the Raj Bhavan in Chandigarh is a rather simplistic building originally constructed to be a circuit house. Le Corbusier, the famous Swiss-French architect who designed the city, had planned the “Governor’s palace” as the fourth major structure of the Capitol Complex. While three structures—the Secretariat, Legislative Assembly, and the High Court—were built, the Governor’s palace was shelved.

“It is reported to have been Prime Minister Nehru who, on a visit to Chandigarh, suggested that the governor’s residence remain in the circuit house building. He felt that the accommodation furnished was quite adequate and that the building of a pretentious Governor’s palace within the capitol complex itself was symbolically unsuitable for a democracy,” writes Norma Evenson in her book, Chandigarh. The Punjab Governor, as a result, continued to occupy the Circuit House designed by Pierre Jeanneret, a Swiss architect who worked closely with Le Corbusier.

The Andhra Pradesh Raj Bhavan was an income tax office that has been repurposed.

But in older states — especially places such as Kolkata, Mumbai, Shimla, and Chennai with their significant colonial presence — the Raj Bhavan is a colonial building, often making use of furniture left behind by the British.

This colonial mindset of a ruler in their palace translates into the way the property is cared for. Governors can convert their lawns into golf courses or fire chefs if they’re unhappy with them.

In Bhopal, it is said that during a visit to the Raj Bhavan, Nehru realised that his favourite brand of cigarette was unavailable, so the staff was flown to the Indore airport to fetch it. But Raj Bhavan officials say there is no historical evidence to support this story.

Raj Bhavans work in silos

Governors aren’t just appointed to do New Delhi’s bidding. The appointment is bound by its own constraints as well. Sometimes, a tough Governor might be appointed in a state at odds with the central government, or it could be a ‘punishment posting’ for politicians that the Centre is unhappy with. The scope for the Centre is immense, but the onus of what should be done with the office is largely on the Governor.

Some throw open the doors of the Raj Bhavan to become the “people’s Governors” and adopt a “people-first approach.” Some turn inwards, preferring to focus on the beautification of the grounds or enjoy a less hectic schedule after a life of active service.

Some see the job as a punishment. SM Krishna, Karnataka’s former chief minister and a Congress leader, famously left his post in 2009 to re-enter politics and become external affairs minister. He made no secret of his discontent with the Governor’s post, according to Raj Bhavan staff in Mumbai. He made his tenure more bearable by setting up a tennis court and playing every day in full sports regalia, headband included — a spectacle that the Raj Bhavan staff and their families would come to watch.

Other Governors have gone the opposite way and adopted causes that came to define their term in office—such as being eco-friendly and renovating the Raj Bhavan to make it more sustainable.

Some Governors adopted questionable causes too. Mohammad Fazal, the Governor of Maharashtra between 2002 and 2004, was keen on promoting male vasectomies. He opened a camp in the Raj Bhavan bluntly named “Population Control Center” and encouraged men in droves to get vasectomies. Around six such camps were held over the course of a few months before the mission was abandoned.

Sometimes, a Governor’s tenure is defined by something else altogether: Shame and scandal. The stint of veteran Congress leader Narayan Datt Tiwari as the Governor of undivided Andhra Pradesh is underscored by a sex scandal in 2009. When he died in 2018 at the age of 93, obituaries described him as the man who disgraced the Raj Bhavan in a scandal that shocked the nation’s conscience.

“Of course we’re nervous when a new Governor enters office, we have to get to know them and their personalities,” says Kashikar, whose work at the Raj Bhavan spans three decades. He lists several Governors and their contributions to the state, taking care to mention the role of each Governor’s wife.

“The role of the Governor of Maharashtra, as defined in Schedule V of the Constitution, his responsibility as the Chancellor of public universities, his mandate to ensure equitable development of all regions of the state — a unique provision for Maharashtra — and his exalted status as the constitutional head, contrasts the general view of the Raj Bhavan being merely a decorative institution,” says Kashikar. “This apart, the Maharashtra Raj Bhavan holds a special place in the hearts of the people as a cultural heritage precinct that has witnessed the transition from being the “Government House’ during the British Raj to a ‘Raj Bhavan’ in free India.”

This is the gap in the perception of the Governor’s office today.

“Nowadays, we only talk about the Raj Bhavan in political terms. We’ve forgotten about the cultural legacies,” adds Kashikar. “The contribution of a Governor’s wife and families is also immense but never discussed. Each Governor has left their unique mark on this office.”

During the 51st Conference of Governors and Lieutenant Governors at the Rashtrapati Bhavan in 2021, former President Ram Nath Kovind encouraged officials and their staff to visit their counterparts in other states to learn and share their best practices. This was never followed up.

The staff and groundskeepers at Maharashtra’s Raj Bhavans, though, aren’t concerned about how their counterparts are doing. “Everyone says Maharashtra’s Raj Bhavans are the best-maintained,” says garden superintendent Dinesh Deshpande, who oversees the Raj Bhavan lawns in Pune and Mumbai. “The Raj Bhavan in Mumbai is known as the queen among all Raj Bhavans,” he adds.

So it’s up to the Governors to pick and choose what they like best. According to C Vidyasagar Rao, who was the Governor of Maharashtra from 2014 to 2019, Mumbai is different because of the “legacy of hard work” of its staff. He is responsible for opening up the Raj Bhavans of both Mumbai and Chennai to the public. It was Rao’s curiosity that led to the discovery of an underground bunker (now a museum curated by historian Vikram Sampath and inaugurated by Modi in 2022) under the Malabar Hill premises.

“The Raj Bhavans mostly work in silos,” admits Kashikar.

The role of the office

Whenever a President visits a state, the Raj Bhavan serves as their camp office. Any further political role of the building depends entirely on the Governor.

Essentially, every Raj Bhavan is kept ready to throw open its windows and spring into action. Pantries are kept passably stocked, silverware is always polished, and wooden floors are scrubbed and polished every few weeks.

Any top state representative could stay at the Governor’s residence, and no stone is left unturned to ensure the guests are cared for. In Pune’s Raj Bhavan, an abandoned exercise cycle — procured brand new for Modi during his visit in 2021 — is still cleaned and dusted, ready for action, in case there is any.

One of the most important functions of the Governor’s office is to insulate universities from political influence. The Governor acts independently as the ex-officio chancellor of all public universities in the state and has free rein over all university matters.

“The Governor is a support to the institution,” says Ujwala Chakradeo, vice-chancellor of Mumbai’s Shreemati Nathibai Damodar Thackersey (SNDT) Women’s University. “A governor’s representative is present for important meetings, and the vice chancellor is appointed by the Governor, who is the chancellor of the university. He chairs ‘Senate’ meetings, which takes many policy level decisions and passes the annual budget of the university.”

Of course, this has also led to issues in some states. In Kerala, the high court recently restrained the Governor after the latter issued showcause notices to vice-chancellors of eight universities for violating University Grants Commission norms. The appointment of vice-chancellors is another sticky wicket between the state government and Raj Bhavan in West Bengal. The Banerjee government faced a setback at the Supreme Court after filing a petition against the Governor’s selection of vice chancellors across universities in the state.

Raj Bhavans have also physically ceded space to universities. In Pune, the premises were so large that the original stone building, constructed in 1864, now serves as the administrative block of the Savitribai Phule University. Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras also stands on the old Chennai Raj Bhavan’s territory.

Governors can also perform an important administrative role in states with large tribal populations. During Mangubhai Patel’s tenure in Madhya Pradesh in 2021, the Bhopal Raj Bhavan set up a tribal welfare cell. Patel extensively toured the state and visited all 52 districts within two years of his tenure, an official from the Raj Bhavan said. The Governor’s office is currently working toward enforcing the New Education Policy 2020 and reviewing the University Act in the state.

In Punjab, the Governor is also the official administrator of Chandigarh, the shared capital of Punjab and Haryana. Administrative activities regularly take place in the Punjab Raj Bhavan; a steady stream of visitors also pours in to see the Governor.

There have also been instances of state governments accusing the Raj Bhavan of overreach. CV Ananda Bose, Governor of West Bengal, has drawn the ire of the Banerjee government on several occasions; the Trinamool Congress (TMC) even tagged him as a “BJP agent”. In a step to reign in the violence during the panchayat election in July 2023, the Governor opened a “peace room” in the Kolkata Raj Bhavan with a 24×7 helpline for those who were allegedly threatened. Bose even urged the railway minister to start a “peace train” from Kolkata to Darjeeling.

The colonial tradition of excess

The Rashtrapati Bhavan has no official say in the functioning of the Governor’s office. There have been no official statements on cutting down expenditures, and there were no follow-up meetings after the 51st Conference.

Some more prudent governors, like Punjab’s Banwarilal Purohit, have stopped using tomatoes in the Raj Bhavan kitchens, owing to high prices. He recently went so far as to forbid officials from travelling to New Delhi by air and staying exclusively in 5-star properties.

The reverse happens too. Accusations of misusing state funds plague the Raj Bhavan. In 2014, the BJP government dismissed then-Gujarat Governor Kamla Beniwal, who proved to be a thorn in the side of the Modi government. One of the supposed reasons for her dismissal was the alleged misuse of government funds in service — Rs 8.5 crore on air travel in about five years in office.

In fact, excess seems to be built into the office—quite literally.

The first Raj Bhavan was built on a sprawling campus in Kolkata in 1803 by Marquess Wellesley, then-Governor-General of India. It was so opulent that it made a £63,000 dent in the East India Company’s coffers. That’s nearly £4 million (or about Rs 42 crore) today.

The building was eventually occupied by the Viceroy of India until the capital of the British Raj was shifted to Delhi. In 1892, it became the first building in India to have electricity and an elevator. It has 60 rooms, a huge central hall, a throne with pure silver craftsmanship, and Chinese-winged cannons.

And even then, there were questions on whether all this was necessary.

Ultimately, the East India Company accused Wellesley of mismanaging funds. The Governor-General was summoned back to England, chastised by the Company’s board of directors, and lost both his job and his house. But not before giving Kolkata the rubber-stamp gift of the Raj Bhavan.

With inputs from ThePrint’s Chitleen Sethi from Punjab, Iram Siddiqui, from Maharashtra, Sreyashi Dey from West Bengal, Sharan Poovanna from Karnataka, and Akshaya Nath from Tamil Nadu.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)