Bhopal: About 25 kilometres outside the city of Bhopal is a colonial-era relic infused with a healthy dose of kitsch — a freshly painted clock tower topped with a coat of arms and dour latin lettering.

The Shrewsbury International School India’s campus, which opened doors last month, mirrors the philosophy on which the franchise has been founded. Fragments of the UK have been transplanted from the British countryside to Madhya Pradesh — staff members, the Cambridge curriculum, and a culture. Water sprouts from beneath the wings of a white marble unicorn statue. The admin building, with its exposed brick, has the same veneer of ornate detailing. Lamp post fixtures that look like they’ve been accidentally deposited from London to Bhopal and marble columns which have taken inspiration from the great parliamentary buildings of the West.

A Dutch teacher has just purchased a shiny ghagra-choli from Bhopal’s New Market to attend this evening’s garba celebration — eagerly announcing its place of purchase.

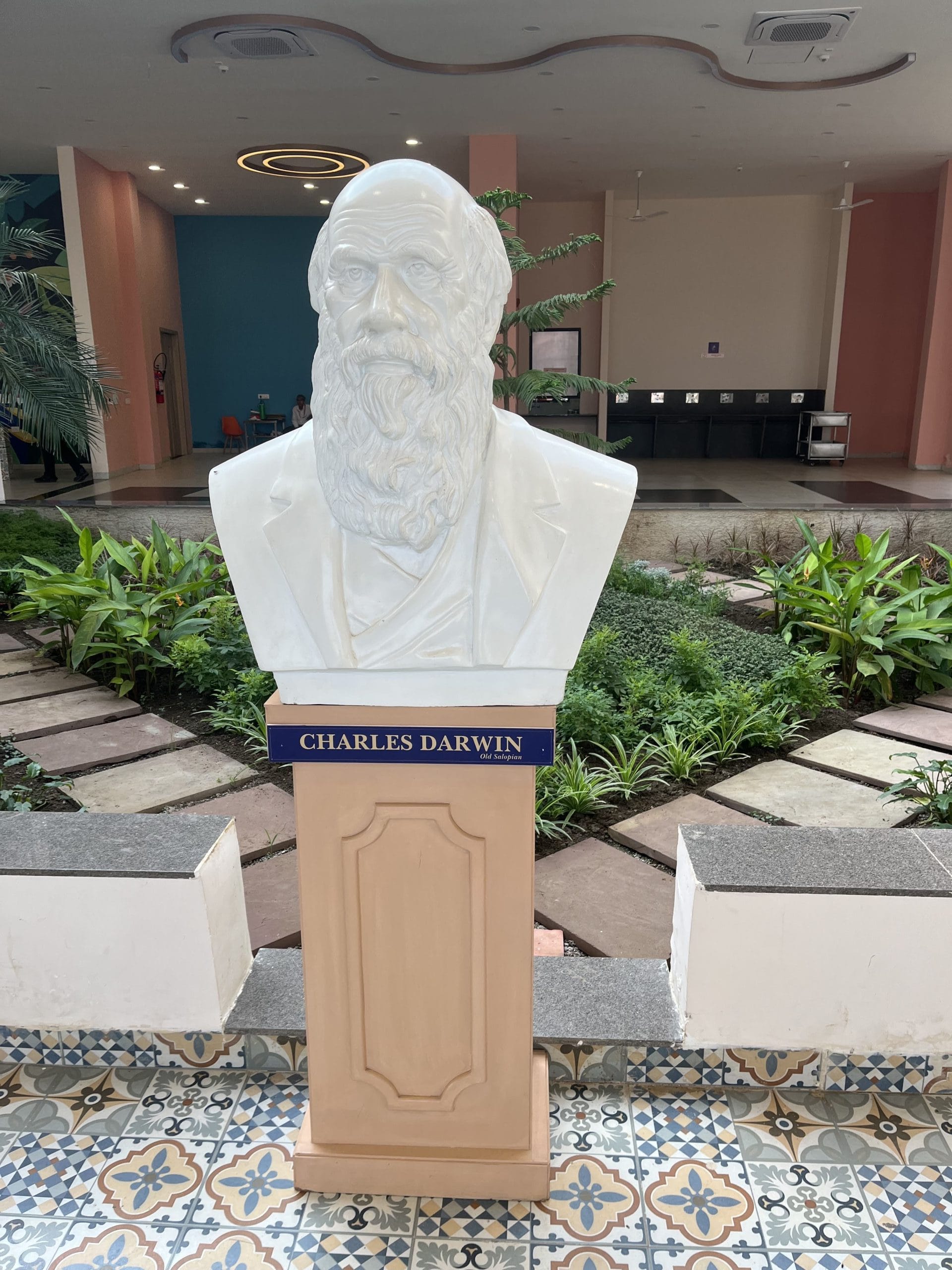

Ten new British boarding schools are en route to India, while three have already set up shop. This new-age passage to India is banking on Indians’ ever-expanding aspirations to clinch a global stamp. After decades of Doon, Mayo, Welhams, Sanawar came a fresh crop of elite schools like Pathways and Woodstock. Now, it’s the British residential schools that are in vogue — catering, in large part, to a new money elite searching for supposed best in the business. At Shrewsbury, a Charles Darwin bust, “an Old Salopian”, sits outside the cafeteria where students are heaping piles of rajma chawal and dahi bhalla onto their plates.

“India is having to change very quickly. And that’s where the real opportunity lies — it’s a wider recognition of the ever increasing number of parents who want their children to have global opportunities,” said Dominic Tomalin, founding headmaster of Shrewsbury International School India. “This is not the world of the 1950s or the 1960s.”

But the school itself claims not to be replicating a British public school, but contextualising it for a largely Indian student body. And it’s far from the only one.

Other than Shrewsbury, Harrow International School, which boasts of a startling array of illustrious alumni — from Jawaharlal Nehru and Winston Churchill to Benedict Cumberbatch and James Blunt — opened its Bengaluru offshoot in 2023. The Wellington Group of schools has a branch in Pune, a day school which is due to turn boarding in 2027. Weighty legacies and hundreds of years of cultivation have been handed to local giants; Shrewsbury is owned by Jagran Social Welfare Society, Harrow is run by Amity International and Wellington by the Unison Group. What they also have in common are hefty fees — parents are forking out upward of Rs 20,00,000 a year to give their children access to insulation. They study in India, but not quite. These schools appear to function in an elite vacuum — giving wealthy Indians the key to an aspiration: British culture and education at subsidised rates.

Charterhouse, founded in 1611 on the skeleton of a monastery in Godalming, Surrey, is opening its school in Goa in 2027. Bedford will become the first British girls’ boarding school to enter India, and will operate out of Mohali, Punjab.

It’s self-evident that India has the cultural and linguistic breadth of Western and Eastern Europe combined,” he said. “And there will always be Indians who want to send their children to boarding schools in the UK

– Dominic Tomalin, founding headmaster of Shrewsbury International School India

This growth fills the needs of both Indians and the UK schools. On one side is the intangible upwardly mobile aspiration. On the other is the lure of a large market of cash-rich Indians.

“This reflects not just the appetite among Indian families, but also the confidence these legacy institutions have in India as a long-term market,” said Namita Mehta, founder of The Red Pen, an education consulting company in Mumbai. “Their presence signals a significant shift: India is no longer just a source of students for British schools abroad, but an emerging destination for British schools within its own borders.”

The parachuting of British schools into Asian markets has become key to their survival — a profit-spewing machine. A 2023 report by the Private Education Policy Forum found that between 2011-12 and 2020-21, 40 British schools received £18.7 million in tax breaks and a profit of £98.2 million from “overseas satellite campuses.”

In India, these schools advertise extensively. Phrases like “a legacy unfolds on Indian soil” are paired alongside the usual flexes — campus size and the internationalism of the cohort. “Learning doesn’t end when the bell rings,” is how Harrow advertises its emphasis on co-curricular activities, before going on to refer to the “Harrow values.” Students and teachers also partake in creating promotional content — sombre-faced behind MacBooks or discussing their latest MUN or international Olympiad.

“A new world of possibilities is opening up India. Are you ready to be a part of it?” is how Shrewsbury introduced itself in 2023.

British boarding school fairs are held regularly at 5-star hotels in cities like Delhi and Mumbai, where prospective parents are treated to a compact, marketable version of the education and lifestyle that their children could be recipients of. Just last week, the Harrow team hosted parents at the Hyatt Regency in Delhi.

Tomalin was earlier an officer in the British Army and moved lock, stock, and barrel to Bhopal. His son Henry is also a student at Shrewsbury. Ruddy-faced with a crop of white hair, Tomalin is dressed in a suit, on the lapel of which sits a Shrewsbury school pin. What also separates the British faculty from the Indian staff members is their attire. Nearly all of them dress formally, a loose tie signifying the day’s end.

He travels extensively. Over the past year, he admitted to having traversed the length and breadth of the country — studying the market and seeking out potential recruits. According to him, recruitment has largely consisted of “major cities” due to the school’s hefty price tag. Although, they’ve also conducted drives in Kanpur. But the school also wants to cater to the diaspora, and is also seeking out cities like Dubai and Singapore. He’s selling the now-lucrative prospect of a logistics-free life. Children spend hours on the road commuting — when they could have every single facility at their doorstep. He also mentioned that the diaspora harbours a deep “fondness for the homeland.”

“They’re keen for their children to be educated in India. But they want to be part of habits and attitudes that work widely,” he said.

“There’s no escaping me,” joked Tomalin. “Our marketing team works very hard to meet our ambitions.”

Parents are encouraged to have one-on-one meetings with the headmaster. Tomalin markets the brand, the Salopian experience — a necessity, given that most parents have never heard of the school.

“It’s self-evident that India has the cultural and linguistic breadth of Western and Eastern Europe combined,” he said. “And there will always be Indians who want to send their children to boarding schools in the UK.”

And that’s when the brand and conversations around legacy enter.

Parents are also offered to visit the lavish expanse of land on which Shrewsbury has been built. Spread across 300 acres, the school has an Olympic-sized swimming pool — where faculty members are also encouraged to take lessons — and a cricket pitch on which the state cricket team is going to be practicing. Sports like fencing and rowing, seemingly alien to India, are also on offer. Excelling at sports obscure in India gives students a leg up. They become big fish.

Meanwhile, the Harrow International School Bangalore campus has been designed by CP Kukreja Architects, one of the country’s leading firms. There are auburn brick walls — serious without being austere — an evocation of a modern Britain in Devanahalli, a suburb of Bengaluru where Foxconn is now manufacturing iPhones. Wellington sits beside the Mula-Matta river in Pune, a scenic setting.

Harrow’s student body consists of 17 nationalities — as well as students from Kolkata, Lucknow, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, Mysore. The India campus opened in 2023. Bengaluru already has reputed international schools like Mallya Aditi — an older school which is difficult to get into. But as more British schools make their way into India, they will soon be competing within this flock of schools. Their USP is similar to the other schools. They’re granting students entry into an elite network—and they don’t have to relocate for it. Wellington also relies on an expatriate group of teachers, ranging from the UK and the US to Colombia and South Korea. The Wellington name doubles up as a “badge of honour” when it comes to attracting teachers.

Culture and language

Piers Webb joined Shrewsbury in anticipation of “adventure.” A graduate of the University of Edinburgh, his friend’s father is one of the governors of the original school. A couple of calls later and he’s an assistant housemaster and Head of Humanities at the Bhopal offshoot.

“I’ve never been to Asia before and I’ve heard great things,” he said. “India really matters globally. It’s important to me to understand it not as a tourist, but as a historian.”

Webb is soon going to embark on an interesting challenge. He’s going to be teaching his culturally amorphous Indian students and their peers about British imperialism — and claimed to be reading “every book under the sun” — absorbing as many perspectives as possible.

“I’m conscious of it,” he said, referring to his position as British-bred and educated and the contrary ways in which colonialism is remembered.

Shrewsbury’s faculty members are split down the middle. Half are “international” with the majority coming from the UK, while the rest are Indian. At Harrow, this divide is about 60-40.

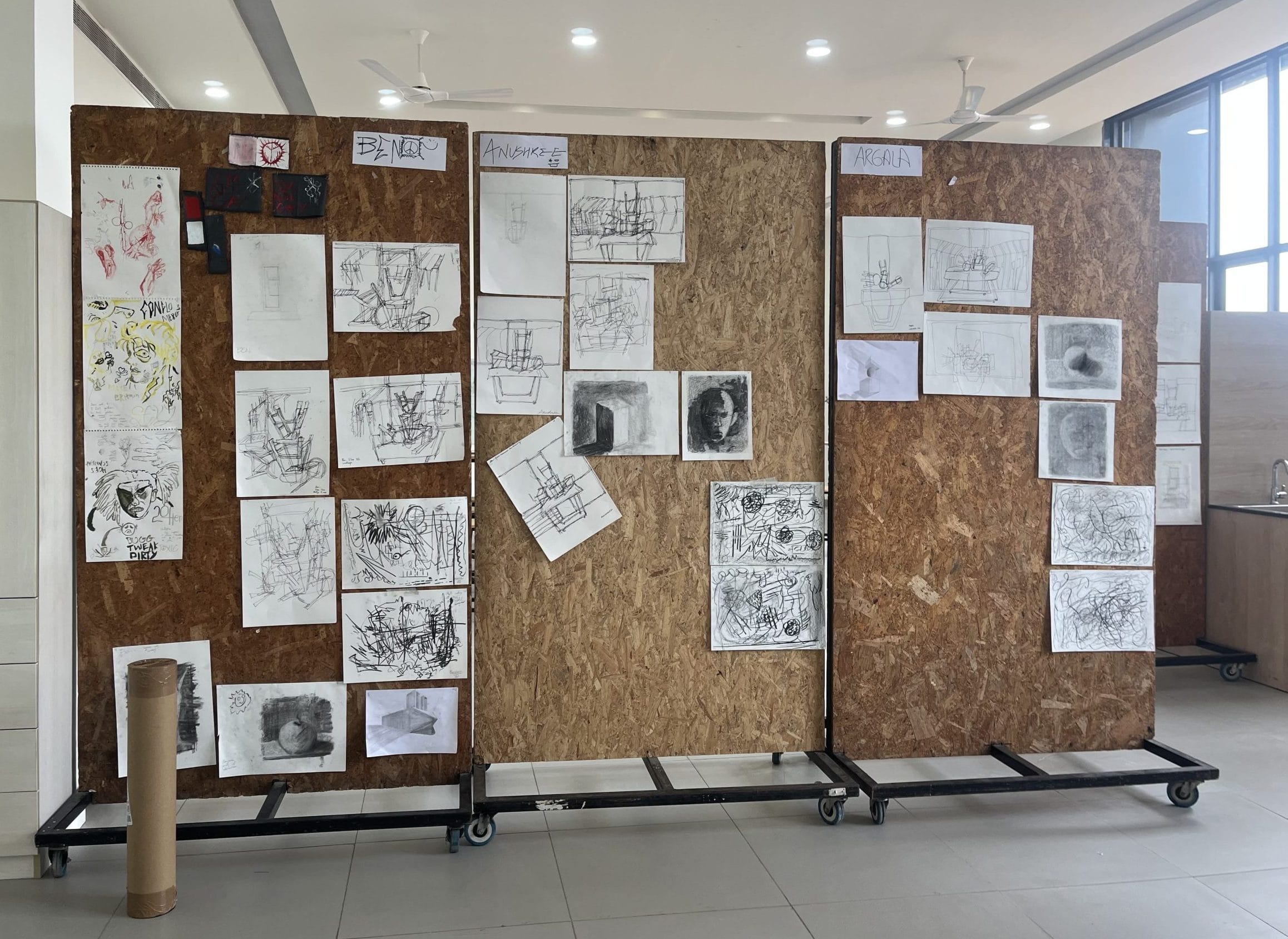

The staff appeared to have taught at international schools in India or abroad, trained in a specific brand of confluence and clash. Shrewsbury staff members maintained that they were not replicating the UK campus, but were meshing the two education systems and cultures together to create something entirely new. The school functions on the Indian calendar. Students are working on a Ram Leela as part of their drama class, and the on-campus indoor sports centre was practically vibrating with Bollywood music as part of a garba evening.

According to Tomalin, the integration of the New Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has worked to the benefit of international schools.

”The NEP moves India towards the thinking of our school. There’s no single focus on intellectual development,” he said. “There’s a focus on other skills and extra-curriculars.”

However, what the NEP also emphasises is a focus on learning in regional languages. Shrewsbury offers Hindi and Sanskrit while Wellington was pushed to venture into offering Marathi.

Simon Small, who teaches languages at Shrewsbury, previously taught at Harrow in Bangkok — where, he said, about 85 per cent of students were “wealthy Thai children.” While advertisements and website content showcase a blend of nationalities, a major chunk of the internationalism comes from the children of faculty members.

Also read: Who are the kings of India’s billion-dollar KYC industry? Identity is big business

For the elite

Sonia Khan and her husband were driving on the Hoshangabad flyover. All it said about the school was that it was a British co-ed boarding school, but that alone was enough to pique her curiosity. The contradiction was obvious. All it usually has are advertisements for jewellery. She began to google furiously and her data was picked by an educational consultancy who paved the way for her to visit the school. She had never heard of it before.

Both her children were studying at one of Bhopal’s top schools. But, she said, discontent was creeping in. Students were getting into fights and hurling abuses at each other. She wanted more from her children and had started researching other options — Indian legacy boarding schools like Welham and Mayo.

Madhya Pradesh has its fair share of legacy schools like The Scindia School in Gwalior and the Daly College Indore, as well as a number of schools offering International Baccalaureate (IB) and the Cambridge curriculum. Scindia, an all boys school founded in 1897, also boasts of the “modernity” that lies behind its century-old campus.

What is constructed and sold as a shared system of cultural values is also a sub-section of the colonised mind. Anything British automatically signals elite and upper crust in the way that American culture and schools do not.

“In normal schools, everything is about ratta [memorisation],” Khan said. “Here they don’t care about exams.”

While she initially visited the campus to take admission for her son, she was blown away by the glitzy, newly built campus — the rooms of which still smell like paint — and decided to send her daughter to the school as well. The expanse of unused space, the seemingly high-brow logo splattered across the campus, the lockers which mention a child’s nationality, and what is called “an aquatic centre” were immediately appealing. When it came to her daughter, it became about safety.

“When I saw the security system, I realised that there was no tension when it comes to sending my daughter,” she said.

Khan’s husband works in construction, and she in interiors. They also have a number of local businesses — including Lazeez Hakeem, a Mughlai restaurant in the heart of the city.

While the image of British schools is located in an institution that is built on military-style discipline and cold campuses where the sun seldom shines, the Jagran Social Welfare Society wanted to give students the feeling of being at home — a luxurious one, that is. A room at the girls’ boarding house contains ample space, a plush, yellow headboard above a neat wooden bed, and an ample stream of sunlight.

The majority of students at Shrewsbury come from Mumbai and Pune — the closest metros. However, they want to cater to the “subcontinent” as well as the larger Indian diaspora. At Harrow, their primary school only has students from Bengaluru.

Other than rich Indians, it’s the expat community that has emerged as a pivotal market. About 25 kilometres from Harrow is the Foxconn factory — the scaffolding and production of which has been accompanied by a fleet of senior executives. Recently, the Foxconn team floated the idea of a “strategic partnership” with the school, in order for the children of their senior staffers to secure spots for their children.

“Our selection process is very stringent. We only choose deserving candidates,” said a Harrow representative, adding that it was Foxconn who sought out the school.

In Pune as well, what has worked to Wellington’s advantage is the presence of start-ups and tech infrastructure in the city — which has also driven expats toward the relatively pollution-free city — a major plus point.

Meanwhile, for pollution-soaked Indian parents, it’s the allure of an alternative education that draws them in. The Cambridge curriculum and the IB are understood as bypassing traditional Indian standards of teaching which are now seen as restrictive and suffocating for certain students.

Almas Virani moved her son Aryaan, who studies in class 9, from Bombay to Bhopal on the promise of holistic learning.

“My son has an exceptionally high IQ. I got him tested. But teachers [at his old school] weren’t able to understand that,” she said. “He’s the brightest kid but he was being told that he was always asking irrelevant questions. He felt like he wasn’t fitting in.”

The school uniform — as is the case in the British schools as well — is an import. Students are dressed in navy blazers and trousers on what is a blistering Bhopal day. Some are in full uniform, while others are more relaxed — with rolled up sleeves or the glimmer of a pierced ear.

Aaron belongs squarely in the former category.

“I’ll give you one word: opportunity,” he said. “Over here, I get to make my own opportunities. I’ll be going for inter-school competitions that I’ll be organising myself with the deputy headmaster. The growth is immense.”

A ticket to good life

The appeal of any elite school — in India or abroad — is rooted in an unspoken agreement. The lakhs — sometimes even crores invested — are the chassis of a gateway to a prestigious foreign university. And the networks built are said to secure the rest of a student’s life, potentially helping them to sail through a difficult job market.

“These schools surround kids who have every possible advantage with a literal embarrassment of riches—and then their graduates hoover up spots in the best colleges,” wrote Caitlin Flanagan in The Atlantic. While Flanagan is referring to a select group of private schools in the US, the principle may well apply to elite schools across the globe — where parents are clamouring to get their children tickets to the top.

Ivy league universities and other top institutions privilege ‘well-rounded’ students. An ideal candidate not only has excellent grades, but is a national level squash player, and performs Shakespeare plays in his free time.

That’s why it’s no coincidence that these schools are located on the fringes of city limits. They need the space to equip their students with the infrastructure that will permit them to access the one-way tickets that will guarantee their future.

“Parents are also highly discerning consumers. University placements remain a key consideration, and as these new British schools evolve, their track record will be highly scrutinised,” said Mehta. “Many are still in their early stages and have yet to graduate their first cohorts, but over time, placements will become the measure by which they are judged and compared.”

Also read: Patna is now a city of museums. Making its history great again

A litmus test

In the last decade, the Indian university system has also expanded by leaps and bounds — with several private universities like Ashoka and Krea modelled on top liberal arts US universities setting up shop. However, for many parents of a certain class, sending their children abroad remains a litmus test for their future. But according to Mumbai-based education consultant Viral Doshi, attending a British boarding school in India has “no incremental value.”

“They are wonderful experiences, but there is no incremental value and local Indian schools are equally good,” he said. “I would look at schools which have a good track record rather than looking at whether they’re English schools or local schools. A track record is important for admissions.”

Doshi added that it takes 10-15 years for a school to build its profile to get into top universities. If an ISC student has a 90 per cent in their board exams and an IB graduate has a 38/45, the ISC student is a better candidate. However, if the students are on par, the Cambridge curriculum or the IB might have a slight edge.

But that’s not all today’s children are looking for.

Neel Kothari, an 11th-grade student at Shrewsbury, wasn’t always hell-bent on life abroad. He assumed he’d wind up at a college in Mumbai University. But when his father visited, the senior Kothari returned unimpressed.

“People bunk at local universities. They don’t realise how important those 2-3 years are,” he said.

But other than the ostensible shortcomings at Indian universities, British schools also become crash-courses for a life outside. For Neel, his “main aim” was to imbibe a culture.

“I want to learn from them — how they think, how they talk, how their businesses work,” said the student.

Engine of India’s growth story

China has long been the gold standard for international campuses and continues to be number one. The Independent Schools’ Council Census 2024 shows that China was the “largest-source market” for UK schools, with 5,824 students. Harrow has campuses in Beijing, Chongqing, Guangzhou, Hengquin, Nanning, Shanghai, and Shenzhen.

Essentially, India’s the new kid on the block. But hopes are high because of a shared intangible value system that makes Indians malleable — they fit in easily to the British system.

“We have a lot in common. We share similar values. I think schools here will fare far better,” said Peter Willett, Deputy Headmaster at Shrewsbury. Willett previously taught at the Sedbergh School in China. “A lot of schools have seen China as the place to go. But they failed because they didn’t quite understand China, or didn’t communicate enough.”

China is also making things difficult for international schools to set up their outposts. Students now have to follow “a specified curriculum” until the ninth grade and Harrow Beijing, which is bilingual, had to stop using its British name, according to a report in Bloomberg.

According to Willett, so far, setting up in India seems to be “far easier” than China.

While the ease of doing business has long been considered a misnomer by foreign entities in India, it is the tie-ups with local partners that have helped them stay afloat. Staff members at Shrewsbury said it would’ve been “impossible” without the Jagran Social Welfare Society — the proprietors of the DPS group of schools in Bhopal.

“Working with a respected group with a strong presence in India ensures cultural alignment, regulatory ease and operational efficiency,” said the Harrow spokesperson. “Amity’s extensive resources provide a solid foundation.”

Meanwhile, for JSWS President Abhishek Mohan Gupta, helming Shrewbsury is about crafting India’s tier-2 story — presenting it as the real engine of the India growth story.

“Central India is one of the biggest areas in terms of population, but has no big boarding school,” he said. “It had legacy schools, but no big schools. Today parents generally want their children to be one or two flights away at most. If you see how Bhopal is placed, it is pretty much the centre of the country.”

But a British boarding school still might seem like a risky bet, particularly when one takes into account the alumni networks — the fact that Indian legacy boarding schools have politicians, actors, writers, and big business owners to assist students in their ascendancy to success. Meanwhile, for most Indians — these are new schools. The legacy carries weight but the schools aren’t part of their cultural fabric.

These schools, however, are aware of this. Shrewsbury plans on amping up access to its own network — generations of Salopians, as their alumni are called — for parents and students to be enthralled by.

“Our brand is more international. And that’s where the students are headed,” said a staffer. “We’re not banking on Bhopal,” added another, laughing.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)

Why not invite British students themselves to study in this UK schools in India? Cost of living is high in UK. It will benefit them also, while bringing foreign exchange as well.