New Delhi: Over 200 people queued outside a store in Indiranagar, Bengaluru, at 8 am on a Saturday. Shrugging off hangovers and skipping workouts, they waited more than two hours on 2 August for a shot at the prized product. No, it wasn’t a line for the latest iPhone Pro Max 17. It was for a limited-edition pair of Comet sneakers made in collaboration with Naru Noodle Bar—both Bengaluru-based brands.

“We sold all 450 pairs in 45 seconds,” said Utkarsh Gupta, co-founder of Comet, adding he couldn’t believe the demand for an undiscounted Indian product; each pair cost nearly Rs 6,000. “The line spanned past the Apple store next to ours. Their manager came out and said we don’t have a launch today. But I told him the line wasn’t for them.”

Sneaker culture is booming in India. What was once just performance gear for athletes has turned into a lifestyle symbol — a mix of fashion, identity, and aspiration. From boutique drops in Bengaluru to counterfeit markets in Delhi’s Karol Bagh, sneakers have become the new markers of self-expression and flex. With the gap between formal and the casual becoming narrower, the sneaker market has got the springs. They are now worn in the workplace, at Diwali functions and even under wedding dresses.

Adidas designed sneakers exclusively for Akasa Air’s cabin crew. The Vice-President of India was seen donning a pair while hosting the President of Mongolia at Rashtrapati Bhavan. Deepika Padukone matched a white pair with her red-beaded wedding-reception dress and actor Tanuj Virwani reportedly owns almost 300 pairs.

Sneakers now make up nearly a quarter of India’s footwear market, driven by Gen Z’s hunger for limited editions, resales and bragging rights. Indian brands are chasing young buyers with pairs themed around sports, anime, food, films, festivals, cars, and video games. The market was worth $3.8 billion in FY24 and is expected to reach $6 billion by FY32.

“There’s a fundamental change in what is acceptable footwear now,” said Arjun Vaidya, an early-stage consumer investor and sneaker enthusiast, who rotates between his 15 pairs of sneakers for conferences, work meetings and even festivals. The Indian variant is even more interesting. “You can wear sneakers with kurtas, suits, playing a sport, on a night out – and earlier these use cases had different kinds of shoes, which sneakers have replaced.”

Such is the sneaker craze in India that it has even sprouted an entire festival.

“We are expecting 30,000 people over two days in Mumbai,” said Nikunj Duggal, co-founder of the Indian Sneaker Festival, which will be held in December. A mix of both foreign and local brands will have stalls alongside performances by rapper Lil Yachty and singer Tyla. “The language of the Indian consumer has changed. People want to support Indian brands and artwork, and they’re proud to wear that.”

The global giants — Nike, Adidas, Puma, Converse — long ago mastered the art of storytelling through shoes, teaming up with sports superstars, rappers, and fashion designers to create cultural capital. Homegrown Indian brands are now customising that formula for a local crowd.

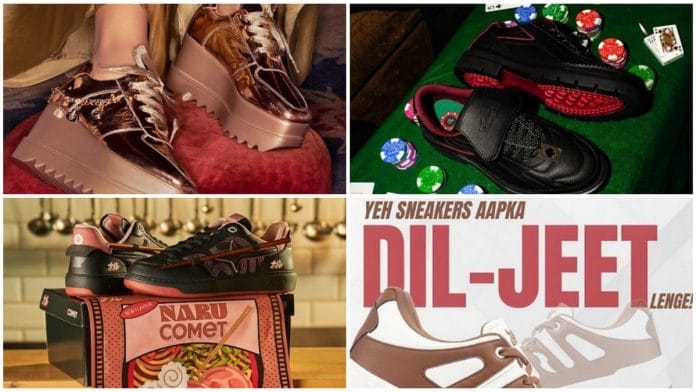

Delhi-based design house Gully Labs, launched in 2023, collaborated with Royal Enfield. Ranbir Kapoor’s clothing and shoes label ARKS dropped sneakers inspired by Lay’s chips. Other than its Naru sneakers, featuring a chopstick on each side, Comet tied up with Assam-born artist Santanu Hazarika for a black-and-red customisable pair. And Knickgasm presented Ranveer Singh with a Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani-themed sneaker, which retails on their site for around Rs 16,000.

In the last 10-15 years, global brands have started seeing shoes as not just a sports utility product, but a lifestyle or culture-oriented product

-Comet founder Utkarsh Gupta

People around the world buy sneakers because of the cool factor. But what really matters is the story the brand is building for itself. Many are going back to the retro style. Nike’s Air Jordan 1 had the storied reputation of being thrown by the NBA. Waffle trainers were popular in the 1980s and 1990s. Adidas Hoops is selling the basketball classics even today. The self-tying sneakers from Back to the Future that Nike made are still talked about.

In India, too, sneakers need a smart mix of price and story — like partnering with a popular noodle bar or using Hindi script as design for the desi grunge.

“Indian brands have managed to build culture and aspiration to get people to pay top dollar for their sneakers,” said Vaidya, who has invested in Comet. “And the way they’ve been able to do that is tie in with the right taste-makers.”

Also Read: Indian women bikers are revving up Royal Enfields, Hondas. Bankers, beauticians & bahus

India’s sneaker awakening

Sneaker culture was born on the basketball courts of America. Originally designed as performance footwear to help athletes up their game, the shoes soon bounced off the court and into a subculture of their own.

In 1985, Nike released the black-and-red Air Jordan 1—Chicago Bulls superstar Michael Jordan’s first signature shoe, and a departure from the all-white norm. When the National Basketball Association banned it for violating uniform codes, Nike turned the outrage into marketing gold. The campaign declared: “The NBA threw them out of the game. Fortunately, the NBA can’t stop you from wearing them.”

The floodgates had opened. For the first time, a sports shoe became a status symbol. It signalled rebellion, assertion, and identity. Over the next few decades, Adidas, Nike, Converse, and Puma dropped shoes with rappers (Kanye West, Run DMC), popstars (Billie Eilish, Rihanna), skateboarders (Tony Hawk), and even brands like LEGO, PlayStation, and Heineken to emphasise exclusivity and extravagance. Sneakers went from athletic gear to lifestyle trophies with cult followings.

“In the last 10-15 years, global brands have started seeing shoes as not just a sports utility product, but a lifestyle or culture-oriented product,” said Comet founder Utkarsh Gupta, who was influenced by his time studying in Chicago, the hotbed of sneaker culture.

“T-shirts have massive amounts of real estate—you can print whatever you want. But with sneakers, it’s the recognition that creating stories on that limited canvas is extremely hard.”

Wearing a fresh pair of Adidas Yeezys or Converse All-Stars quickly became a form of self-expression – a way to wear your identity on your feet and be a part of the “cool” crowd. As sneaker culture spread beyond schools, Silicon Valley’s casual workplaces made it acceptable in offices too.

Soon everyone from doctors and finance bros to delivery workers and students was in sneakers, mixing colourways to match outfits, moods, even eye colour.

The trend permeated India through NRI relatives, celebrity endorsements, and later, Instagram reels—and spiked during the pandemic’s athleisure boom. VegNonVeg, launched in 2016, was one of the country’s first sneaker boutiques, catering mainly to affluent youth: students returning from abroad and professionals familiar with global fashion and travel.

The people who aspire to own Nikes have tilted toward first copies because there was no brand offering them a good aspirational product in this price range

-Ankit Singh, founder of Zaydn

For most Indian buyers, though, sneakers from global brands remained out of reach. A standard Nike or Adidas lifestyle pair costs between Rs 10,000 and Rs 20,000. Rarer limited drops can go for a couple of lakh in the resale market, while collaborations with fashion houses fetch even higher prices—the Louis Vuitton Nike Air Force 1 currently sells for close to Rs 9 lakh. That’s where Indian brands saw an opportunity for a desi spin with prices to match.

Comet’s Gupta mapped the market as a two-by-two matrix—high price, high aspiration; low price, low aspiration. Global brands crowded the high price, high aspiration segment and unbranded sneakers covered low price, low aspiration. What was untapped, he said, was the space for products that were high aspiration and “attainable”.

Brands such as Comet, Gully Labs, and Neeman’s sit in that space, priced between Rs 4,000 and Rs 7,000—less than half of what international giants charge. Indians, with rising disposable income, could now turn to homegrown brands to satisfy their cultural cravings.

“Nobody was going to a party and saying, dude, check out my shoes or this brand,” said Gupta, recalling Comet’s early days with a hint of passion in his voice. “Shoes in India were missing that canvas for self-expression. That’s what we wanted to create.”

Comet’s first shoe was a mango-themed sneaker, tugging at the country’s collective love for the fruit. The box was packed with hay and the shoes were green and yellow. Every element was part of a narrative. It didn’t just sell a shoe. It screamed ‘India’.

“We all smile during mango season when we unbox a mango—it’s just a beautiful emotion,” said Gupta, adding that the design created chatter because of the sentimental value. “It’s a product you love to wear because people like the storytelling.”

Sneakerheads, meanwhile, are getting bolder with their choices, going beyond plain, solid colours to more audacious designs with multi-coloured soles.

“I don’t want the first thing on the shelf. When I buy shoes, I’m looking for both utility and to stand out,” said 30-year-old Tanveer Padode, who carries his all-green pair of Air Force 1s even on business trips.

Padode, who runs a construction data and insights platform in Mumbai, laughs about some of his past purchases, including a Dwayne Wade basketball sneaker with loud black, yellow, and red colours—but that hasn’t stopped him from continuing to experiment.

Other enthusiasts, though, are turning nostalgic, hunting for retro sneakers and classic silhouettes. “

At first, I was drawn to the hype pairs—the limited drops, collabs, and the kind of shoes that everyone was chasing. But over time, my taste started to shift,” said 33-year-old Jaikaran Singh, who first got into sneakers through skateboarding culture.

“There’s something timeless about older models, especially when you realise how many of today’s ‘new’ designs are rooted in those originals,” said Singh, who owns over 30 pairs. “It’s less about chasing hype and more about appreciating the craftsmanship, the design heritage, and the nostalgia behind each pair.”

Designed for desi tastes

With the market ripe for the taking, sneakers tailored to Indian tastes are flourishing. Among the new crop of founders is 35-year-old Shibani Bhagat, who turned a personal pain point into her brand 7-10 Sneakers.

“I’m kind of a short person. I constantly have to wear heels which hurt my feet, and couldn’t find sneakers with heels,” said Bhagat, who launched her brand in February 2022. “I found a gap in the market, and the research showed me the potential for a brand to be built.”

For their heel sneaker, the company took a gamble. They decided to create their own sole rather than following the convention of using off-the-shelf ones. Seven-Ten designed and patented its ‘Oriformi’ sole, named after the Japanese art of origami. The 2-2.5-inch stack sole is both chunky and lightweight.

“In India, the average height of women is five feet two or three inches—and that’s why they feel the pressure to wear heels. We wanted to create something that was both dressy and comfortable,” Bhagat said.

The sole wasn’t her only innovation. The team redesigned the shoe box (“Indian feet are slightly wide”), ditched suede (“It catches dust more easily”), and used PVC for their monsoon collection. Their first limited drop was the Taash sneaker—card-game themed and released just in time for Diwali.

“We took a formal sole and put a sneaker on it. We keep trying to push the boundary of what more we can create in this space,” said Bhagat. Only 52 Taash pairs—like a pack of cards—were made and are now sold out.

The only occasion that rivals festivals in importance on the Indian social calendar is a wedding. And with people splurging on outfits, venues, and decor, it’s no surprise that bridal sneakers are becoming a part of the mix. Especially with the bride and groom taking to the dance floor all night at cocktail sangeet events.

Comfort has become the new luxury. And sneakers pair well with lehengas—it looks cool, edgy, and statement-making

-Tanushri Biyani, founder of Anaar

Tanushri Biyani, a self-proclaimed “shoe whisperer” who founded footwear brand Anaar in 2023, got the idea of making bridal sneakers when she saw friends wearing white Keds under their lehengas.

Then, her sister-in-law fractured her leg and wanted a sneaker with heels. It nudged Biyani to design the first prototype as a favour.

“She wanted the height, but the comfort of a sneaker,” Biyani said. “Comfort has become the new luxury. And sneakers pair well with lehengas—it looks cool, edgy, and statement-making.”

Customers value shoes that reflect their personality and don’t punish their feet on their special day, according to Biyani.

“Twenty per cent of our clients opt for some form of customisation,” she said, adding that this can range from embroidered initials to heart-shaped danglers to various charms that decorate the sneakers. “We can change the heel height, foot width—all based on a customer’s preferences.”

At their newly opened flagship store in Mumbai’s Kamla Mills, space has been set aside for a customisation lounge. Now customers can sit with Anaar’s master karigar (craftsman) and designers to come up with bespoke footwear.

Who the sneaker brand partners with for promotion is customised for an Indian audience. Pictures of Shalini Passi of Fabulous Lives of Bollywood Wives fame and Neha Dhupia wearing the brand’s wedge sneakers occupy prime real estate on the website. And on each sneaker page, a ‘customise your Anaar’ WhatsApp button catches the eye.

Also read: Tamil Nadu is the new China+1 for shoes. Crocs, Nike, Adidas foot India’s manufacturing push

Counterfeits vs cost-effective originals

Droves of young sneakerheads flock to Delhi’s Karol Bagh, where vendors flog Adidas, Nike, and New Balance knockoffs in every colourway. The fakes are almost indistinguishable from the real thing—a happy middle ground for those chasing a fresh white pair of Air Force Ones without blowing an entire month’s salary.

“Customers come to us from Haryana, Punjab, and Bihar just to buy our sneakers,” said one vendor, as buyers crowded his stall. “All of these are copies, but look at the quality. And we sell every pair for Rs 1,000, cheaper than other vendors.”

India’s new-age sneaker brands have largely steered clear of the mass market—it’s almost impossible to make shoes that cheap. Yet, as Indian Sneaker Festival co-founder Nikunj Duggal pointed out, Rs 1,000 pairs still make up 90 per cent of the market.

Ankit Singh, the 28-year-old founder of men’s sneaker brand Zaydn, has recognised that gap. He is leaning on his family legacy to build an affordable sneaker empire.

Zaydn means “born of fire”, he said at his multi-storey factory in the Delhi State Industrial and Infrastructure Development Corporation complex in Udyog Nagar.

“The people who aspire to own Nikes have tilted toward first copies because there was no brand offering them a good aspirational product in this price range,” said Singh, sitting in an office filled with stacks of Zaydn sneakers in yellow boxes.

The language of the Indian consumer has changed. People want to support Indian brands and artwork, and they’re proud to wear that

-Nikunj Diggal, founder of the Indian Sneaker Festival

With a spark of excitement in his eyes, Singh pulled out his products from various boxes – all priced at below Rs 1,500. He proudly held up a brown, white and black pair, tagged with a yellow flame charm.

Singh says his fight is against first copies – high-quality counterfeit versions of popular sneaker brands. And he has the technical know-how to win the battle. As a child, he would visit his father’s factory, which produced white labelled sports shoes for brands like Woodland and Campus. Singh even studied at the Footwear Design and Development Institute, Noida.

Zaydn’s sneakers are built entirely in-house, from stitching to packaging, which helps in keeping prices down. Only the sole is outsourced from China, although Singh said these too will soon be manufactured at the Udyog Vihar factory. The company, he added, can make pairs for as low as Rs 500-600.

“College students find Rs 4,000-5,000 sneakers too expensive. We tell them that instead of buying one pair for that price, buy three of ours so you can match your shoes with your outfit,” he said.

The model is working. Zaydn’s revenue rose from Rs 2.5 crore in 2021, its first year, to nearly Rs 10 crore by the third. Social media has been a big driver, with quirky reels showing people overestimating the price of Zaydn sneakers or calling out fake shoes under the tagline ‘Be a Zaydn in a world full of first copies.’

Like other brands such as Comet and Gully Labs, Singh knows the holy grail of consumer culture lies in storytelling.

“A product cannot sell itself. When you add a layer of packaging, a layer of story—people start connecting to it,” he said.

With a jump in his step, Singh grabbed his latest prototype—a sneaker with 3D icons imprinted on the sole: airplanes, trophies, mugs.

“Each icon is associated with our brand of fire in some way. The airplane signifies the fire of travel,” he said, pointing to a sheet with the various icons and their meaning.

He rattled off a string of collaboration ideas that could help turn Zaydn into a household name, from a tie-up with a beer brand to reels co-produced with travel influencers: “We are now dropping our own culture.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)