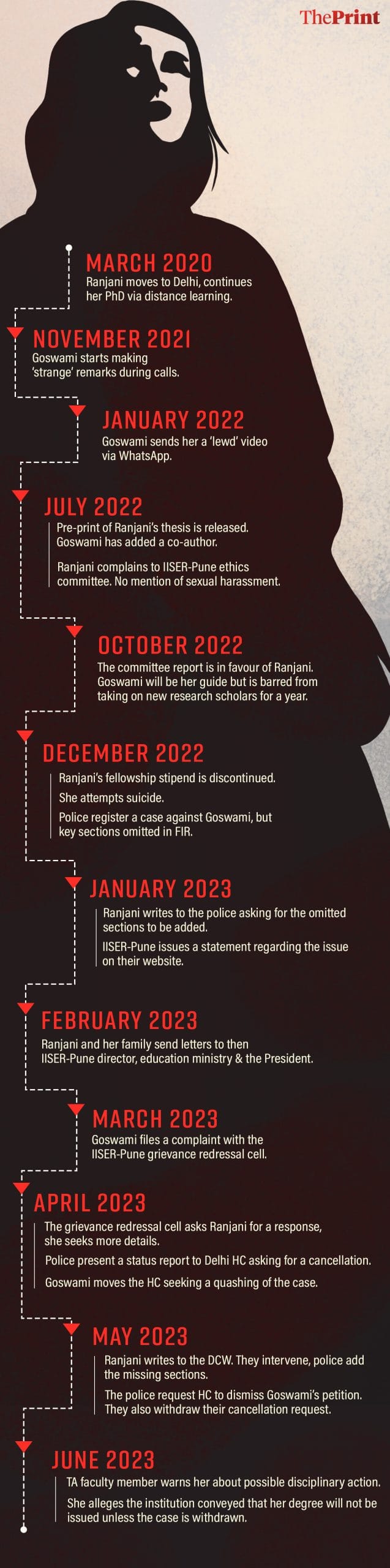

New Delhi: Ranjani* fought to reclaim her PhD thesis her professor and guide had ‘stolen’ from her, fended off his unwanted online ‘romantic’ gestures, took it to the ethics committee, the women’s commission and the police. Then on a bitterly cold Delhi winter morning in December 2022, the MS-PhD student from the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Pune swallowed a bottle of antidepressants in an attempt to end her life.

The final year PhD student’s nearly one-year-long fight to save her career exposes the darker and oppressive side of a PhD guide-research scholar relationship.

She survived the suicide attempt. But it took five months — and the Delhi Commission of Women’s intervention—before the police finally added the sections of sexual harassment and abetment of suicide to the FIR against the guide. He is fighting for the charges to be dropped in the Delhi High Court, but Ranjani’s PhD thesis, which he had allegedly attributed to another student, still languishes unpublished.

“IISER Pune has conveyed to me in June that unless my case against the guide is withdrawn I won’t get my degree,” Ranjani alleged.

ThePrint has reached out to the chairperson of IISER-Pune’s board of governors Sudhir Mehta regarding the allegation. The copy will be updated when a response is received.

Having to make the difficult trade-off between silence over sexual harassment and jeopardising their thesis is a student’s nightmare. And it can happen in Ivy Leagues like Harvard and elite IITs in India. Research scholars, especially women, are vulnerable, and their only recourse is an enquiry under the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (PoSH) Act 2013. But Ranjani claims she was never made aware of the PoSH committee when she reached out to the college authorities.

He told me he missed my presence on campus. It creeped me out. I didn’t feel safe, says Ranjani

She has written to the education ministry multiple times and to the President of India twice since December but has not received a response. “We have sent at least a dozen representations to [education] minister Dharmendra Pradhan, but to no avail,” a family member of the complainant said.

She alleges that the professor had been making inappropriate remarks and sent one “lewd” video to her since January 2022, but she never reported his behaviour for fear that it would jeopardise her life’s work. Her hesitation was not unwarranted.

“A PhD guide not only has discretionary powers over a thesis, their signature also holds ultimate power in the student getting admission in postdoc programmes,” said Lal Chandra Vishwakarma, head of All India Research Scholar Association.

The relationship may not be sanctified like the guru-shishya parampara, but the power dynamics are clearly and disproportionately tilted in favour of the supervisor.

In May, a student at Aligarh Muslim University accused her PhD guide of withholding her thesis because she didn’t respond to his alleged sexual advances. A research scholar at Kamarajar Government Arts College, Tamil Nadu wrote to Chief Minister Stalin accusing the commerce head of department of sexually harassing her and withholding her doctorate. And Kalakshetra Foundation in Chennai was rocked by scandal after students accused a senior teacher of sexually harassing them. These are instances of harassment on campuses across India in the last year alone. In 2020, IIT-Madras was at the centre of a media storm after a scholar accused seven people on campus, including two professors of sexually abusing her for years.

“A guide can make or break a career. Without their recommendation, a student’s career in academia comes under serious peril. A young academic’s life heavily depends on their guide’s opinion,” said Vishwakarma.

Also Read: ‘No panga with minister’—Haryana woman sprinter’s lone battle against sexual harassment

Uneasy calls, texts

An MS-PhD integrated course Maths student at IISER-Pune, Ranjani has been pursuing her degree from her home in Delhi since the Covid-induced lockdown in 2020. She is a member of Mensa International, the world’s oldest high-IQ society, with a promising academic career. Today, she is isolated from her peers and none of her teachers have reached out to her, she claims.

Titled ‘A Semi Markovian Approach to Model the Dynamics of Stock Price’, her thesis looks at a way to predict stock price movement, and can also be used to decipher patterns in weather forecasting, and stratified healthcare.

IISER-Pune refused to discuss the case citing subjudice but had issued a statement on its website saying that despite its “best efforts towards redressal”, it was unfortunate that the student and her family decided to file an FIR against her supervisor and the administration.

“Mathematics was my life. It has been snatched from me. My health is in shambles. I am turning 30, and instead of looking to settle down and start my career, my life and future are plunged into darkness because of one man,” said Ranjani.

On 2 January 2022, Ranjani received a WhatsApp video from her PhD supervisor, Anindya Goswami, associate professor of mathematics and data science. It wasn’t unusual for them to communicate over Whatsapp.

But the video he allegedly sent had nothing to do with her research. It was a clip of two human-like figures, a male and a female, floating across the universe in an embrace to a cover of a popular song by the American band Maroon 5.

“I didn’t know how to respond to that video. It made me so uncomfortable, why was my PhD guide sending me such an obscene video,” said Ranjani. She didn’t respond to the clip, which she shared with ThePrint. Later, Goswami sent her a message saying that it was sung by his wife, but it still made her uncomfortable. She alleges that it was the latest in a series of strange remarks he had been making during their many conversations since November 2021.

The college had assigned Goswami as her PhD guide only after she relocated to Delhi. While in college, her interactions with him were limited to MSc lectures in one that he taught.

He was curious about her relationship status and if she had a boyfriend. “He told me that not having a boyfriend is unnatural,” she alleges. The conversation, she says, happened over the phone.

His behaviour started making her increasingly uneasy. She was under pressure to return to campus in Pune.

“He told me he missed my presence on campus. It creeped me out. I didn’t feel safe,” she said.

Goswami denied all allegations levelled against him and called them ‘baseless’. “There is no question of me having done such a thing. The matter is subjudice for quashing. I have full faith in the justice system,” he wrote to ThePrint in an SMS. He has petitioned the Delhi High Court for the charges to be dropped and lodged a complaint with the institute’s grievance redressal cell.

Ranjani did not share these incidents with anyone. After seven years, she was so close to the finish line and did not want anything to derail her from getting her degree. She couldn’t afford to antagonise her supervisor.

In July 2022, Ranjani’s inbox pinged with an email she had been waiting for—a preprint of her thesis. But when she opened the document, she saw that she did not have sole authorship. Another woman was listed as a co-author. She couldn’t use her thesis to get a PhD degree.

“It felt like the ground beneath my feet was going to swallow me whole,” she said.

In a panic, she called Goswami to confront him about this addition. The woman whose name had been added to her thesis had completed her MSc in 2021 and was pursuing an MBA at Delhi University.

“I don’t understand why her name was added to the publication,” she said.

According to Ranjani, Goswami told her that he had promised co-authorship to the woman, Srishti Gupta.

“He said he had promised Gupta to launch her into academia,” she said. “He also said that my mathematical quality was not of any use to him. I am a PhD Maths student, what other ability was he looking for? ”

According to the police’s court filings, Gupta said that she has nothing to do with new research work and that her name had been “deliberately” added by Goswami. She did not respond to ThePrint’s phone calls or WhatsApp messages.

Ranjani filed a complaint with the ethics committee at IISER-Pune in July 2022, which concluded that Goswami had failed to properly credit her work. But she made no mention of sexual harassment. The committee barred him from taking on any new research scholars for a year.

But it was decided by the ethics committee that she would work under him for another year to get her PhD, ThePrint has a copy of the committee’s report that was published in October 2022.

“I tried to seek time with the director on a personal level time and again but it wasn’t given to me. Also, in several emails, we had told the college that I don’t feel safe with him. But the college’s response was discouraging. They didn’t want to listen to me,” she said.

IISER-Pune declined to respond to queries sent by ThePrint over email. “The matter is now sub-judice at the Delhi High Court. Hence we cannot comment on the matter,” the registrar of the college said while providing a link to an earlier statement issued on its website.

In the statement, IISER said it had offered an independent faculty member to oversee the publication of the students’ research and mediate between her and Goswami. It also offered the support of counsellors. But Ranjani was unhappy with this.

“The independent faculty member is a college friend of Goswami who had earlier asked me to drop the case against him. How impartial is he? How can I trust him?” she asks.

Not a POSH case?

In early December, Ranjani consumed an entire bottle of antidepressants. Her parents rushed her to Swami Dayanand Hospital in Dilshad Garden in time for doctors to save her life.

Ranjani’s parents and siblings rallied around her. In February 2023, they sent emails with specific allegations of sexual harassment to then director of IISER-Pune, Jayant Udgaonkar. ThePrint has copies of these emails. Until then, Ranjani had never approached the college about the professor’s alleged sexual harassment.

“I didn’t know about the existence of a POSH committee on campus. In over seven years with the college, there has never been a POSH sensitisation workshop,” she said.

Preeti Karmarkar, a Pune-based social activist who is an external member of IISER Pune’s internal complaints committee, recalled that Ranjani’s case was discussed in one of the four ICC meetings conducted by the institute in a year, as per its POSH policy. “We did discuss the case, but it looked like a case of ethics violation not sexual harassment,” she said.

Karmarkar was surprised by Ranjani’s allegations. She said the ICC is very proactive, and that it had probed several harassment complaints in the past. To the best of her knowledge conducts sensitisation workshops.

“However, I have not been present at these workshops, but as far as I know they have been regularly conducted,” Karmarkar said.

ThePrint wrote to IISER-Pune’s POSH committee to inquire about sensitisation campaigns but did not receive any information on it.

“Members of the POSH committee had tweeted after my suicide attempt, demeaning me and supporting the accused,” she said. Two members of the POSH committee had tweeted statements supporting the college’s version of events, one of them dismissed Ranjani’s allegations as “gossip”.

“How could I trust faculty members who are friends with each other and were supporting the accused openly, to conduct a fair inquiry?” she asks.

Also Read: Kalakshetra Chennai has a PoSH problem. Students fume, gag order imposed, art world shaken

Widespread issue

The path to a PhD can be a long and lonely marathon where the guide is the coach—someone to lift the flagging spirit and keep the scholar on track.

“In some cases, outstation students also depend on their guides for emotional and familial support. It is very common for a PhD student to become an extended family member of their guide,” a former MPhil student said.

Many PhD students ThePrint spoke to said they had to run errands for their supervisors, dust their houses, or rearrange their cupboards. Refusal to do such things is not a choice.

“One does these little things to get into the guide’s good books. Sexual harassment is just an uglier version of this entitlement a guide feels,” said a student from IISER-Mohali.

A simple search of #phdmetoo on Twitter throws a series of tweets by anonymous students from various institutes detailing accounts of harassment at the hands of their guides. But nothing has come out of it.

These incidents of abuse are not limited to Indian campuses. At Harvard University in Boston, 38 professors signed an open letter defending a colleague who had been accused of harassing students but later retracted it in the face of overwhelming evidence.

Lack of faith in existing redressal mechanisms is one of the main reasons for reticence among scholars to fight.

“Students complained that nominated committees were often perceived as protecting the faculty. They felt that no serious action will or can be taken against teachers,” read a 2013 report by UGC-appointed Saksham on Safety of Women and Gender Sensitisation on Campuses.

A PhD student from Aligarh Muslim University, who alleged she was sexually harassed by her guide, finally turned to the police in May 2023 because she didn’t find the report of her college IC to be fair.

“The committee members have to be on campus along with the professors who are their colleagues. Why would they penalise them in favour of students?” she says.

In 2016, Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Internal Complaints Committee gave a clean chit to professor Atul Johri. Eight students had filed police cases against him. It concluded that it was Johri who was under threat by the women who had accused him of harassment.

“For five years JNU students protested…The way the IC guarded the professor would discourage any student from raising a complaint in the future in JNU as well as in any college outside of it,” a former PhD scholar from JNU said.

The 2013 SAKSHAM report found that reporting of sexual harassment on campus was abysmally low. Around 83 per cent of colleges declared to the committee that they had “never” received a single complaint of sexual harassment on campus.

To check the absolute power of a research guide, the University Grants Commission also mandates the formation of a Research Advisory Committee (RAC), or doctoral committee, where independent professors conduct annual research presentations to review the progress of the student, and if the students’ work is on time.

The committee members have to be on campus along with the professors who are their colleagues. Why would they penalise them in favour of students? – AMU PhD student who accused her guide of sexual harassment

Between April 2020 and March 2021, the UGC received 103 complaints (52 from Universities and 51 from colleges), and no fresh complaints in 2021-2022. As per its consolidated report, zero action was taken on the complaints, while most were disposed of.

IISER-Pune does not fall under the purview of the UGC but under the Ministry of Education, which Ranjani has written to.

Students say these committees are hardly effective. “If the student grievance is strictly about work, the RAC can solve the matter, but those are not teachers you can necessarily confide in,” a former PhD student said.

A representative of ChintaBAR, an ad hoc student group in IIT-Madras said that members of doctoral committees are mostly appointed by guides.

It’s not uncommon for students to find themselves isolated even on campus. IIT-Madras has come under media glare after four of its students—two were PhD scholars—died by suicide in four months between January and April 2023. While neither was sexually harassed, one of the victim’s brothers blames his PhD guide for undue pressure.

Also Read: ‘Bigger than Olympics’. Wrestlers brave heat, mosquitoes, abuses to mount Nirbhaya-like protest

Fight continues

Ranjani was stonewalled by the academic system and also by the police. The first time a police complaint was registered in Delhi against Anindya Goswami was in December 2022, when she was battling for her life.

An FIR against the professor was registered in December, but several allegations were omitted from the complaint including that of sexual harassment, said Ranjani. It took countless visits to police stations, failed attempts to meet the DCP, and finally an intervention from the DCW for the police to register to include the relevant section to the FIR.

She emailed Deputy Commissioner of Police Rohit Meena in early January, detailing allegations of sexual harassment, and asked the police to add those sections to the existing FIR. However, nothing happened for five months.

By 13 April this year, the police were ready to close the case. They presented a status report to the Delhi High Court seeking its cancellation. After this, Professor Goswami moved Delhi High Court seeking a quashing of the FIR.

“The thesis cannot be termed as property. As per the investigation conducted so far, no cognizable offence is made out. Therefore investigation of the current case has been cancelled. Cancellation report has been prepared and the same will be filed in court soon,” read the report.

In desperation, Ranjani wrote to the Delhi Commission for Women which intervened on her behalf in May. It was then that the police added abetment to suicide and online sexual harassment to the FIR. On 22 May, they requested the HC to dismiss the petition by Goswami. They also withdrew their cancellation request.

Goswami has been booked under section 67 of IT Act (sending/publishing content with sexually charged material), and section 63 of the Copyright Act(infringement). And under various sections of the Indian Penal Code, including section 354D (stalking), 509 (insulting modesty of a woman), 506(criminal intimidation), 306 (abetment to suicide), and 511 (attempt to commit offence).

“As per statement of victim, the petitioner Dr. Anindya Goswami has committed a heinous crime and later on in connivance with Dr Jayant Udgaonkar, the director, IISER, Pune, Maharashtra hatched a conspiracy to ruin the life of the victim and compelled her to commit suicide,” police told the Delhi High Court.

Unhappy with the slow police investigation, the family is now demanding the constitution of a Special Investigation Team.

Ranjani has no choice but to put her flagging faith in the system. She cannot afford a lawyer, can’t get a job because she has yet to get her degree and her meagre fellowship stipend of around Rs 12,000 (reduced from 35,000) was discontinued in February 2023.

Goswami also filed a complaint on 23 March with the institute’s grievance redressal committee of the institute alleging “harassment” because of “false propaganda against him”. The cell sent an email to Ranjani in April about his complaint and sought a reply from her. In response, she asked for details on the mandate of the redressal committee.

In June, Ranjani received another email, from a faculty member from the math department. This time, it was a warning—disciplinary action could be taken against the student.

This article is part of a series called PoSH Watch.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)