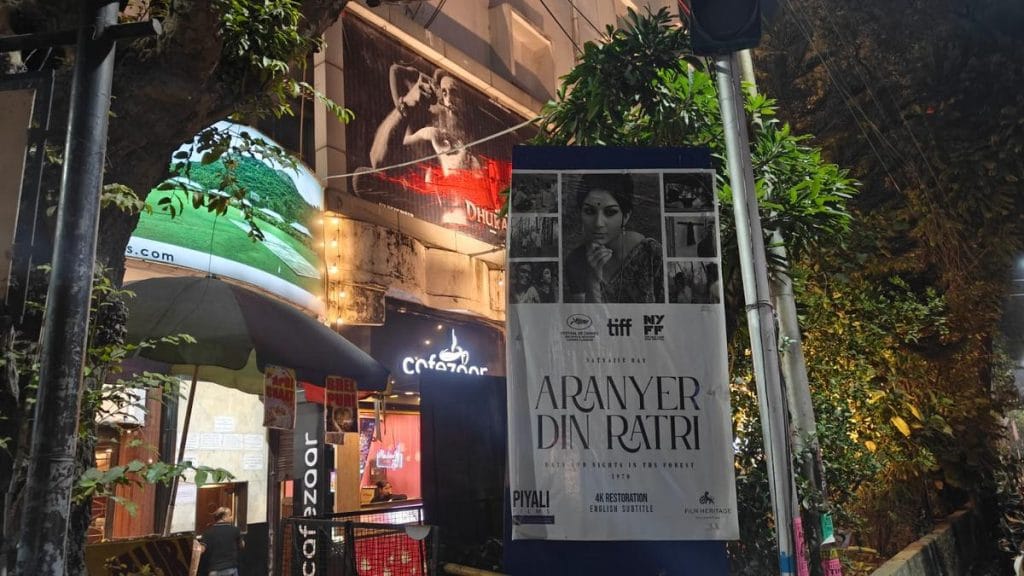

Kolkata: At half past noon on a warm Sunday, a long queue snakes down the pavement outside the single-screen Priya cinema hall in South Kolkata’s leafy, café-lined Deshapriya Park. A glowering, muscular Ranveer Singh towers overhead in a Dhurandhar poster, but on a large board at eye level is a more permanent marker of the hall’s identity: a doe-eyed Sharmila Tagore in Satyajit Ray’s Aranyer Din Ratri.

For the middle-class patrons of the hall, which has stood here since 1959, Priya is the option that manages to be both comfortable and cost-effective without offending their social sensibilities. There is an INOX and another uniplex called Menoka within a 4-kilometre radius, but it’s Priya that is the go-to for bhadralok families, clandestine lovers, and boisterous student groups from Jadavpur University.

“Menoka’s audience is from the lower classes. Lots of rickshawallahs go there,” said Abhijit Bhattacharya, a regular from his Jadavpur University days through romantic date nights with his wife to family outings now.

As one of the few thriving single-screen stalwarts in India, Priya has carved out a niche as a middle-class bastion. It is not a grand destination cinema like Jaipur’s Rajmandir, nor has it radically changed its model into a hybrid, budget cinema like Delite in Old Delhi’s Daryaganj. Instead, it capitalises on the Bengali love of nostalgia, regular technology upgrades, and a shrewd mix of Bangla, Hindi, and English films.

Kolkata is a city that lives in the past and nostalgia brings in people to watch movies at Priya. But we need to focus on the younger people. It is not enough to just have the concept of a single screen but to offer multiplex-like facilities

-Agnivesh Dutta, director of Priya Cinema

Then there’s the Dutta factor. The father-son duo who run the show are fixtures in Kolkata’s elite circles: 62-year-old Arijit Dutta even does movie cameos, while his son Agnivesh has worked on Netflix projects and has represented the family on red carpets, including at Cannes. In its heyday the family’s production house Purnima Films, named after Arijit’s mother, even backed films such as Satyajit Ray’s Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969).

But more than its links with Satyajit Ray and arthouse beginnings, owner Arijit credits Priya’s longevity to a combination of strategy and positioning. On his polished wooden table, there are piles of files containing cutouts of every article written about the cinema hall, started by his grandfather Nepal Chandra Dutta.

“We have marketed and positioned ourselves for decades, long before multiplexes arrived,” said Dutta. “We did a lot of PR activity from newspaper write-ups, television interviews, to movie premieres, and talks and discussions.”

Also Read: There’s a reason Bollywood loves Rajmandir Cinema. Jaipur’s single-screen hall is a unicorn

The maverick owner

In Kolkata’s party circuit, Arijit Dutta is better known as Dadul. It was at one such gathering that filmmaker Shoojit Sircar offered him a role in Madras Cafe (2013). He was cast in the role of Mallaya, a character based on LTTE’s Gopalaswamy Mahendraraja.

But behind the ponytailed socialite persona is decades of hard scrabble in keeping the hall afloat, entering film distribution, and expanding his business portfolio.

Dutta took over the business in 1990 when it was riddled with debts and cinema itself was under siege.

“This was the time of VCR, piracy, and cable TV showing the latest films a week or two after release. It was a proverbial mess,” he recounted, puffing meditatively on a cigarette.

Dutta had grown up around the film business but came in with a different toolkit. As a child, he had been barred from watching Hindi films for their sometimes bawdy content; Bengali cinema was considered the safer option. He finished school at St Paul’s Darjeeling, studied at Jadavpur University, and completed a management degree from IISBWM in 1986. But with the reins in his hand after his father Ashim’s death, he quickly discovered a nose for hardboiled business.

From screenings at Priya, the business expanded into film distribution, tourism, and public–private partnerships. Over time, Priya Cinema was folded into Priya Entertainments Pvt Ltd (PEPL), with a more corporate work culture and diversified revenue streams. With Dutta as managing director, PEPL took on distribution for Sony Pictures, Paramount, and Walt Disney, upgraded sound systems to Dolby Atmos, and partnered with the West Bengal and Tripura governments to revive old, dilapidated cinema halls.

Single screens in today’s time can only be passion projects. If I actually leased out the building for a working space, I would earn at least 50 times more. But as long as I am around, Priya will too

-Arijit Dutta, owner of Priya Cinema

Even as multiplexes started taking over, Priya was ahead of its time as the first cinema in eastern India to introduce internet and computerised ticketing. It pursued brand tie-ups, splashed out on premieres, and even sometimes took a bet on new filmmakers.

“Other theatres were not confident about Shiboprasad Mukherjee and Nandita Roy’s Icche (2011). But my father decided to give the film a few shows,” said Agnivesh Dutta, his son. The film went on to do well and Mukherjee later gifted wristwatches to the theatre’s staff as a mark of gratitude.

However, as a realist, Dutta knew that he couldn’t bank on cinema alone and so diversified into tourism. He set up the Eco Adventure Resort at Khairabera in Purulia, an area that once made news as a Maoist lookout zone, and the Temi Bungalow in Sikkim in 2018, along with his wife, Esha Dutta.

“Single screens in today’s time can only be passion projects. If I actually leased out the building for a working space, I would earn at least 50 times more,” he said. “But as long as I am around, Priya will too,” said Dutta.

If he no longer feels “the pull toward it”, Dutta added, he might lease the building out. But with his son now part of the business, that day appears distant. He keeps a hawk’s eye over every aspect of its functioning, with a monitor on his table displaying a CCTV feed from various corners of the theatre.

On a recent Saturday, he had just finished giving an interview to students from the Satyajit Ray Film & Television Institute who are making a documentary on the hall. Of late, he has slowed down his pace of work. His routine includes going over his business affairs, heading to the gym nearby, and then a few hours at the office before retiring back to the family apartment located just above the theatre.

“Now there is a well-oiled system in place. So I like to work less, and make more escapes to the mountains, and relax,” he said.

This peaceful state of affairs, however, comes after a harrowing spell.

A fire and a phoenix

Bengal once had as many as 700 single-screen theatres, which have now dwindled to only 130, including the state-run Nandan and Radha Studio, which promote art-house and independent cinema. In this bleak landscape, Priya is a dark horse. Not only is it commercially viable, it survived two big blows in quick succession.

On 5 August 2018, a fire broke out in the kitchen of a momo restaurant next to Priya theatre. Smoke snaked its way up into Arijit’s office and the film audience was immediately herded out. But though tragedy was averted, it put Priya’s existence on trial. The Bengal government ordered the cinema to renew its fire license, pending which it had to down its shutters.

After a gruelling 6-month period of renovations, paperwork, and revamping fire safety measures, the hall reopened in February 2019. The seats at the theatre were reduced from 785 to 543, and the bill came to almost Rs 45 lakh. Then, just as it was finding its feet again, Covid hit.

What came to the rescue when restrictions lifted boiled down to its affordability, the loyalty of long-time patrons, and a fortuitous slew of hits such as Pushpa: The Rise (2021) KGF: Chapter 2 (2022), and The Kashmir Files (2022).

On a December afternoon, manager Dhiraj Yadav watched his laptop screen refresh every few seconds as bookings rolled in for Dhurandhar.

“The next two shows are also housefull,” he said, with a smile of satisfaction.

Prices play no small part. Stall tickets start at Rs 105, going up to Rs 345 for recliners. It’s still Rs 200-300 cheaper than the nearest multiplex.

It is a cool place to click a photo. Clicking a picture at an Inox makes no sense, but this has history of Bengali cinema

-moviegoer Arnab Neel Basu

At a time when the Supreme Court has rapped multiplexes for their exorbitant food and beverage rates, Priya offers milk coffee for Rs 70 and a patty-and-beverage combo for Rs 180. Popcorn and other savouries are capped at Rs 150.

“I live nearby, and this is our comfort zone,” said Sonjoy Dey, who had come with his sibling for the film. “It’s like watching a movie from our own bari, just on a bigger screen and with other people.”

The Bengal government, too, has noted the need for accessible, affordable halls. On 18 December, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee announced Bengal’s mini-cinema policy, which proposes small, air-conditioned auditoriums of around 50 seats with digital projection systems. The idea is to preserve theatrical viewing even as most old halls have shut. Private players are responding to the gap as well. SVF, eastern India’s biggest film production company, has opened 57 screens across 27 locations in Bengal, including Bolpur, Malda, and Kalyani, to revive cinemagoing in places that have lost their single-screen theatres.

But in Priya, legacy and a certain gravitas are also part of the attraction. Photographs of Arijit Dutta’s father and grandfather line the foyer, as do posters from films produced under the Purnima Films banner and images from past screenings. A vintage car and a piano occupy pride of place near the entrance.

“It is a cool place to click a photo. Clicking a picture at an Inox makes no sense, but this has history of Bengali cinema,” said moviegoer Arnab Neel Basu, trying to hold on to his tub of popcorn.

The Satyajit Ray connection

While other producers in the 1960s were wary of getting involved with Satyajit Ray’s fantasy adventure Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, it was Arijit’s mother, Purnima, who heard the film’s music and convinced her husband, Ashim, and father-in-law, Nepal Chandra Dutta, to take the risk.

The gamble paid off with a 51-week run and a National Award hat-trick for their banner, Purnima Films, which had already tasted success with Tapan Sinha’s Hatey Bazarey (1967) starring Ashok Kumar and Vyjayanthimala, and Arundhati Devi’s Chhuti (1967). It won awards at international film festivals like Adelaide, Auckland, and Tokyo and was in the running for the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

Nepal and father Ashim were also the producers of the Ray classic Aranyer Din Ratri, which was recently restored by the Film Heritage Foundation. The family maintained close personal ties with Ray as well.

“During the height of the Naxal movement in the 1970s, the Golden Bear statuette that Satyajit Ray won for Ashani Sanket was kept hidden under my grandmother’s bed,” said Arijit.

For all his adoption of new technologies, Arijit treats the past with reverence. On the second floor, Priya’s oldest projector is kept on display like a holy relic, but the real living history is projectionist Chand Kumar Mondal. Upon request, he still demonstrates to visitors how film reels were once fitted into the machine.

Last year, Mondal was awarded the Film Heritage Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award for Cinema Projection. The award was presented by director Giuseppe Tornatore—whose Cinema Paradiso centres on a projectionist—at a ceremony held at Mumbai’s Regal cinema hall on 27 September 2024.

His certificate now hangs in Priya’s conference room, sharing wall space with black-and-white photographs of Ray on location.

An old projector is still kept inside the projection room. Mondal recounted the night it almost failed mid-show in 1991.

“It was new and the Sanjay Dutt-Madhuri Dixit film Saajan was playing at our theatre. At one point the projector got stuck, and even the brand’s engineers threw up their hands, unable to make it work again. I took a deep breath, went upstairs to smoke and after that, with the help of another employee managed to get it working again,” he said, grinning at the memory.

For many Bengalis now in their 40s and 50s, Priya was known as the Shah Rukh Khan hall, while another single screen, Navina (also still operational), was associated with Salman Khan films.

“When Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge was showing, the counter stayed open all night,” said Swapan Satra, who has handled queues and odd jobs at the hall for more than four decades. “Before Shah Rukh, women were crazy about Jeetendra films like Tohfa and Himmatwala. The hall was always packed, the gates bursting at the seams.”

Also Read: How Old Delhi’s Delite Cinema outlived Golcha, Jubilee, Novelty. ‘Solution is romance’

A son returns

Heir apparent Agnivesh Dutta took a zig-zag path between Kolkata and Mumbai before settling into his current stint as the director of Priya. The one constant was a love of films, whether he was sneaking down to the theatre to watch them or making them.

The 33-year-old, who has a film and marketing degree from Lancaster University, recalled slipping downstairs to watch every movie screened at the hall.

“I watched the Bengali film Bombaiyer Bombete (2003) 14 days in a row, and while I did not get a seat for Dil Chahta Hai, which was running housefull, I would make sure to go watch the song Koi Kahe,” he said.

Eager to try his hand at filmmaking, Agnivesh started out assisting director Sujoy Ghosh in Kahaani 2 (2016) before joining the family business as an executive. But this first stint wasn’t exactly smooth.

“I spent time at every department, learning the ropes of the business and the daily workings of the hall. But my dad can be very adamant about how things should function at the theatre, and even I was pretty young and immature back then. So it took some time,” he said.

And so back he went to Mumbai to assist Ghosh on the Netflix film Jaane Jaan and the director’s segment of the anthology Lust Stories 2. But the pull of Priya proved too strong to resist and he rejoined the company as director in 2023.

Agnivesh has a bold new vision for the future, built on the solid foundation that his father has built over the last three decades.

“Kolkata is a city that lives in the past and nostalgia brings in people to watch movies at Priya. But we need to focus on the younger people. It is not enough to just have the concept of a single screen but to offer multiplex-like facilities. That is my eventual goal,” said Agnivesh.

It was his initiative to introduce a varied menu with Maggi, nachos, and chicken popcorn to attract younger visitors, especially students and hostellers in various colleges of the city. He also plans to revive his grandparents’ production banner and add new Bengali films to its slate.

But, like his father, he is attuned to the power of the past.

“The advantage we have is that Priya has a rich, layered history and young people now are really into vintage and retro. They come in and click pictures in front of the vintage car or the piano,” he said.

This is the final article in a three-part series on single-screen theatres in India. Read the other articles here.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)