Kotputli: The stone crushers never stop in Rajasthan’s Jodhpura village. Their metallic whir hangs in the air, coating homes, trees, even people’s hair in a fine white dust. Under a banyan tree weighed down by the same dust, villagers gather to protest. Their fight was very different from signing petitions, posting Instagram Reels and meeting in Gurugram cafes to mobilise citizen action. Their protest was about their homes. And they were here to listen to Kailash Meena, who they call the Guardian of the Aravallis.

“This is our village. Our land. Our Aravallis,” he tells them. Fists rise. Voices follow. “We will fight till the end.”

For more than three decades, 60-year-old Meena – soft-spoken, and driving a battered black Mahindra Bolero – has been fighting illegal mining across the Aravallis, the 650-km undulating mountain range stretching from Gujarat through Rajasthan and Haryana to Delhi. When stone crushers arrived in Kotputli’s Jodhpura two years ago, the villagers knew exactly whom to call.

“Delhi’s AQI has crossed 500. People are protesting and the media covers them,” said Neeraj, a local resident, running his finger across the floor of his house to show the chalky residue. “Think about us—the AQI in our villages must have crossed 1000, and nobody is even listening.”

Now, two weeks after the Supreme Court adopted the 100-metre norm, a special vacation bench will hear a suo motu matter concerning the definition of the Aravallis today. However, Meena says his fight is not limited to how the Aravallis are defined, but is about ending illegal mining in its entirety.

“I want the Supreme Court to withdraw its definition of the Aravallis and impose a complete ban on illegal mining to protect the ridges. The Aravallis have already suffered immense damage,” he said.

Activist by accident

Meena does not resemble the new-age, tech savvy environmental activist – no WhatsApp groups, no crowdfunding campaigns. His activism runs on diesel, patience, and persistence: village meetings, handwritten letters to collectors, visits to district offices, and repeated trips to courts driving his sturdy SUV through the potholed, dusty bylanes of Rajasthan’s villages.

For Meena, becoming an activist was never part of the plan. He was a regular man, grazing goats in his fields. “I started my fight to save my home. Suddenly, I was an activist,” he said.

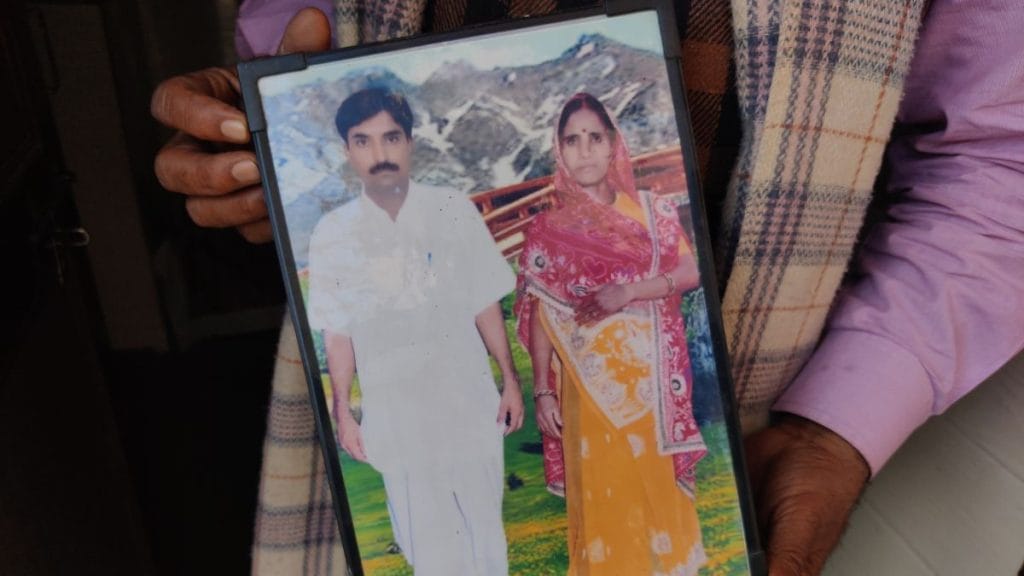

His wife, Kaushalya, was his biggest supporter and main financier, saving up from household expenses to fund his activism.

For the villagers at the foothills of the Aravallis, he is more than an activist. Meena patiently guides villagers routinely on drafting letters to district collectors, the National Green Tribunal, and ministers, detailing their grievances. He is their hero, guide, and mentor.

His fight has acquired urgency again. In recent weeks, protests erupted across Haryana and Rajasthan after the Supreme Court accepted a committee recommendation from the Union Ministry of Environment, imposing a stricter geological definition for the Aravallis, classifying only hills above 100 metres, and within 500 metres of each other, as part of the range.

Though the environment ministry quickly reiterated a ban on new mining leases, Meena remains sceptical.

Also Read: We need an economic pivot on Aravallis. Stop mining, invest in eco-tourism

“I’ve seen several such notices and orders for 30 years. These orders are implemented for a week, and then we are back to square one. The villagers suffer,” he said. “I have learned not to believe anything now.”

Environment lawyer Ritwick Dutta paints a grim picture of how the courts handle mining cases. According to him, courts often dispose of cases by passing orders but rarely follow up on their implementation.

“There is a lack of administrative will, whether it is the NGT or other authorities. There is a lack of follow-up. It is good to pass orders, but it is important to pursue the matter to its logical conclusion,” Dutta said. “There is no point in saying that illegal mining is banned—we already know that it is banned. What is required is regular monitoring.”

Cracked walls, quiet threats

Neeraj, in his 30s, joined Meena six months ago after blasting from nearby crushers cracked his home’s walls and ceiling in Sikar’s Prempura village.

“These blasts feel like hour-long earthquakes. The entire house starts shaking,” Neeraj said, pointing to a fractured boundary wall.

Nearly every household tells the same story – damaged homes, dust-filled air, and convoys of stone-laden trucks, many without number plates.

“Meena ji had visited our village before. Back then, our area wasn’t much affected. But over the past year, everything has changed drastically,” Neeraj said.

The residents have carried out several protests in the last six months. But they were met only with threats and intimidation by the representatives of the mining company, they say.

“Whenever we talk to them, they threaten us,” said Saleh Kumar, another resident. “Then the police arrive the next day, force us onto buses, and warn that cases will be filed against us.”

Now, every night when the blasting is relentless, families take shelter under a temporary tent erected on a sprawling courtyard at one of the houses, afraid their ceilings might collapse on them.

Promises that turned toxic

The distrust in the system runs deep. When a cement plant was commissioned in Jodhpura in 2007, villagers were promised jobs and development. Many ignored Meena’s warnings. But reality struck them soon and hard. Today, they complain of heavily polluted air, illnesses, and unemployment. A joint assessment by the National Alliance of People’s Movements and PUCL described their life as “suffocating,” with mining depriving residents of their most basic human right – the right to breathe.

“The proximity of the village to the mining activities and a cement plant has subjected them to misery… the air they breathe was suffocating, heavy with pollution depriving them of the most basic human right,” the report noted.

Meena now wants to turn scattered anger into a sustained movement. From his modest home in Neem Ka Thana – goats tied to trees, children playing in the courtyard – he calls village representatives across districts. His pitch is blunt, almost like a salesperson’s: “Are you suffering because of mining in your area? This is not only a question of your future or village but also, our country. Join us!”

The effort has a name: Aravalli Virasat Jan Abhiyan. Long hours of discussion over the new wave of protests coalesced into a plan: to reach every affected village and channel the growing unrest into a collective voice from Rajasthan.

“These protests are the result of long-simmering anger over the mining that has affected residents. We just want to channel it in the right direction, so that it’s not misused,” Meena said.

The activism has galvanised a new generation of youth and for the first time in years, Meena’s fight no longer feels lonely.

On 25 December, young protesters against mining gathered in Jaipur, chanting: “Gen Z ekta zindabad (Long live the unity of Gen Z).”

He now gets regular updates from the younger generation and their protests. A message from a young girl pops up on his phone as he speaks. His eyes start to sparkle.

“Though we’ve never seen gods, if angels existed, they would be like you—the very deity of the Aravallis, fighting to save them,” the girl wrote in her message to Meena.

Written in dust and fear

Meena’s battle began in 1997, when a stone crusher came up in his village, Barwala.

Dust destroyed crops, livestock feed vanished, and villagers began falling sick with a disease they had never heard of – silicosis, caused by prolonged exposure to silica dust, that leads to severe lung infections.

“My father used to take our goats to graze there, but there was no feed, and the farmers’ crops were lost,” he recalled.

Letters to officials led nowhere. So Meena marched – literally – walking from village to village with pamphlets on illegal mining.

Slowly, men in the villages began joining his Jan Jagrukta (people’s awareness) march.

“The march was a success. Whichever village I visited, people welcomed me. They made sure that I had food,” Meena recalled with a smile.

But the journey was not a cakewalk. In 2005, armed with RTI documents showing hundreds of crushers operating in Neem Ka Thana, he approached the Rajasthan High Court for the first time.

“I was disappointed with the administration and had a strong belief in the court,” he said. “But until 2010, I kept fighting for my case.”

In February 2010, the court ruled in his favour. Meena printed 200 copies of the order and distributed them in villages and to the mining companies. Yet, he says, the order’s impact never reached the ground.

“Mining didn’t stop,” he said. “It just moved from 500 metres to 700 metres.”

What followed were years of threats, intimidation and humiliation.

In 2011, Meena was arrested and paraded naked through his village to scare others into silence. His elder brother went into shock and died days later. “I had 24 cases filed against me. Eight times, the mafias attacked me. But this… this was just too much,” Meena said, his eyes brimming with tears.

His wife and son advised him to leave the village because the humiliation was “unbearable”.

Yet, he stayed back for the fight.

In 2013, he approached the National Green Tribunal in Bhopal and secured another closure order. Enforcement, he said, remained elusive and violations continued. A 2018 CAG report later confirmed what villagers already knew: Supreme Court orders on mining were routinely violated, with nearly 99 lakh metric tonnes illegally excavated across five Rajasthan districts in five years.

Meena didn’t budge. He continued visits to mining sites and collecting evidence – photos, GPS coordinates, and letters to various departments. He even protested at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar. Nothing changed. Silicosis continued to kill in his village.

“At least 1500-200 trucks carrying stones passed from here in 2025. Now, you can easily imagine the extent of mining,” he said.

When the Rajasthan government in 2019 announced a Rs 3 lakh compensation for victims’ families, Meena scoffed.

“How laughable is this? The government does nothing to save people by stopping mining. Most of these silicosis victims come from mining areas,” he said. “There is value for the dead, but none for the living.”

Faith in system shaken

From district offices to courtrooms, Meena’s fight to save the Aravallis has been marked as much by hope as by disillusionment. But one episode still stands out as a turning point – one that, he says, permanently altered his faith in the system.

In 2015, while Meena was in Jaipur for a public meeting, news broke of a surprise inspection by a judge from the National Green Tribunal’s Bhopal bench in Neem Ka Thana.

By the time Meena rushed back, the judge had already left. Days later, local reports quoted the judge saying that everything in the region was “fine” and that there was no mining activity.

“I was shocked and shattered,” Meena recalled. “My belief in the courts and the judicial system was shaken.”

What followed deepened that sense of betrayal. When Meena visited the villages the judge had inspected, residents told him that a meeting had been held with mining owners ahead of the visit. The roads near the mines had been washed, the surroundings temporarily greened in an orchestrated calm.

“The very next day after the judge left, mining resumed. The roads were once again teeming with overloaded quarrying trucks,” Meena said. “Even the courts couldn’t stop them.”

The battle continues

Last year, Meena returned to the National Green Tribunal, this time over the Sota river. Once a perennial water source for villages in the region, the river had run dry, its course choked by years of unchecked mining and the flattening of surrounding hills.

In his petition, Meena argued that illegal quarrying had altered the river’s flow and destroyed its catchment. The tribunal ordered an investigation. Weeks later, it directed Rajasthan officials to restore the river and its ecosystem.

But a warning, however, came from closer to home even though the case moved in his favour. “You are fighting very powerful people – don’t fight,” villagers told Meena.

Over the years, Meena’s house was raided several times.

“I was treated like a terrorist. My wife would plead with the police to at least let me eat,” he said.

A friend of his was even murdered, Meena claims.

“One of my friends, Pradeep Sharma, who joined my fight was even killed by the mafia,” he said, his voice trembling.

Loss, and a flicker of hope

Through it all, his wife held the household together – farming, tending goats, and funding his travel. Four months ago, when she fell seriously ill, Meena stopped travelling. She insisted he continue.

“She said this was a bigger fight,” he recalled.

He went to one meeting, returned, and showed her photographs. She died four days later.

“I didn’t even know she was seriously ill until the doctors told me she had a blood infection,” he said.

With protests against illegal mining in the Aravallis growing louder, social media is flooded with posts calling for the protection of the old ridges.

However, lawyer Ritwick Dutta believes such online campaigns are short-lived, unlike grassroots movements which have lasting impact.

“For the Meena community, this is about the protection of their livelihood. It is not a luxury—it is a matter of life and death,” Dutta said. “These are Gandhian forms of protest that continue for years, even decades. Social media, on the other hand, is limited and has a very short lifespan.”

Now, as his phone rings again – another village, another complaint – Meena climbs into his dependable Bolero, its windows patched with polythene. It was a gift from his friends 19 years ago to help him with his fight.

His phone sits on the dashboard, ringing relentlessly.

“There is still hope,” he said, starting his car. “Maybe this time, the mining will stop. Maybe this time, we will breathe fresh air.”

(Edited by Stela Dey)