New Delhi: Justice Navin Chawla’s words rang through the Delhi High Court in September. “If you don’t like India, please don’t work in India.”

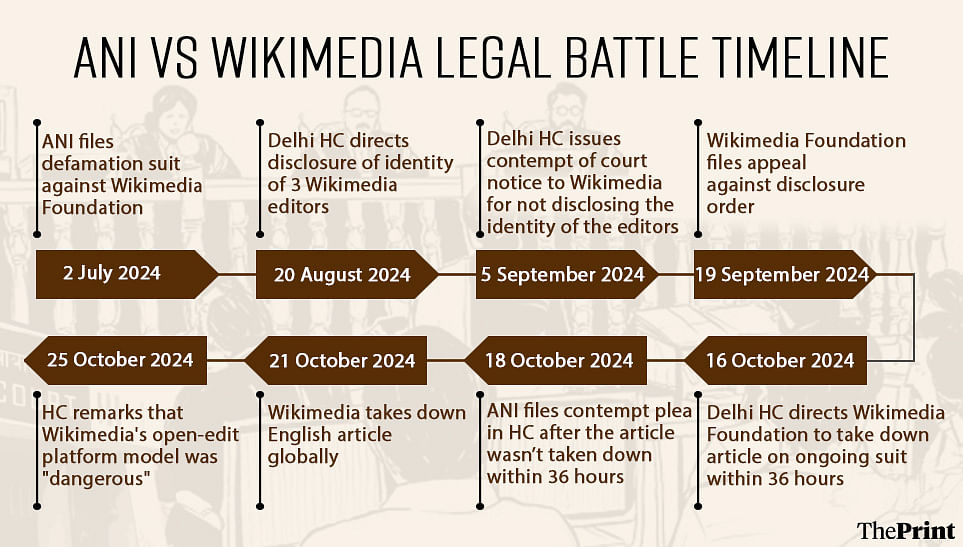

The judge was weighing in on the ANI vs Wikimedia Foundation legal battle. The defamation case has since turned into not just a survival battle for Wikipedia in India but has thrown up questions about the future of free access to information into a whirlwind. “We will ask the government to block Wikipedia in India,” came the next retort.

This isn’t just about ANI’s allegation that Wikipedia, a non-profit organisation, allows negative and defamatory edits, but according to experts and free-speech advocates, the Rs 2 crore lawsuit strikes at the heart of a promised information democracy where knowledge was collectively but freely constructed. It was a heady era back then. But in the fraught times of fake news, misinformation and propaganda, that promise has been contested not just in India but also in France, Germany and the US in the past.

The case in the Delhi High Court has touched on all the hot-button issues. The open-access editing function has been called “dangerous”, the court has said that the system of maintaining the anonymity of users and administrators “will have to go”, and Wikimedia has even been issued a contempt notice.

During the trial, Wikimedia did something that it reportedly hasn’t done anywhere else in the world. It took down an English article after the Delhi High Court order. And now, it has even agreed to disclose the basic subscriber information about the users who wrote or edited ANI’s Wikipedia page in a sealed cover to the court.

In the process, it’s India’s growing reputation as the land of internet shutdowns and opaque embargos that’s at stake.

“Globally, India is yet again being seen as a place that is finding creative ways to stop the free flow of information,” Mishi Choudhary, founder of the non-profit organisation Software Freedom Law Centre India (SFLC) told ThePrint.

Mishi Choudhary’s brother, Kabir Darshan Singh Choudhary is a senior counsel with the Wikimedia Foundation, and was a consultant with SFLC.in for three months in 2019. ANI’s contempt plea against Wikipedia filed on 18 October, after the ANI vs Wikipedia article was not taken down, named Kabir Darshan Singh Choudhary as the respondent. This contempt plea has since been disposed of. He also filed an appeal against the disclosure order in the Delhi High Court, on behalf of Wikimedia Foundation.

In the eye of the storm is ANI’s Wikipedia page. Among other things, it alleged that the news agency “has been criticized for having served as a propaganda tool for the incumbent central government, distributing materials from a vast network of fake news websites, and misreporting events.” This Wikipedia page is still up as the matter remains pending in court, and it still mentions these allegations.

In its defamation suit, ANI alleges that the Wikimedia Foundation’s actions have not only tarnished its long-standing reputation in the industry and among the general public at large but have also subjected it to harassment from the public and its associates from across the globe. The news agency now wants not just the removal of the allegedly defamatory content, but also Rs 20,010,000 as damages.

From questions over revealing the identity of the editors of ANI’s Wikipedia page to the taking down of the Wikipedia page on the lawsuit itself— this is now a head-to-head battle between Wikipedia’s volunteer-centric editorial norms, and Indian laws, including the 2021 Information Technology Rules. While some experts say that the court is well within its right under the existing laws to ask Wikipedia to disclose its editors, other experts express concerns about the impact that this may have on access to information and free expression under Article 19 of the Indian Constitution.

Therefore, beyond the ideas of right and wrong, most tech policy experts are keenly watching how this suit unravels.

Also read: JNU, DU, & AUD professors are rushing from classroom to court. VC office doesn’t listen

Sum of all human knowledge

“The questions around Wikipedia’s architecture and intermediary protections also raise fundamental questions about the sustainability of crowd-sourced knowledge platforms,” said Kazim Rizvi

Wikipedia has always concerned itself with a higher purpose of sorts.

“Imagine a world in which every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum of all human knowledge. That’s what we’re doing,” Wikipedia’s co-founder Jimmy Wales famously said in a 2004 interview. Over the years, it has become the default first platform for anybody looking to read up about anything and everything under the sun.

However, this isn’t the first time the platform has been dragged to court for its content.

It has won some, and lost some.

For example, back in January 2019, Wikipedia had to remove certain allegedly defamatory content about a computer science professor, after the referenced links were found to be inactive by a German court.

However, more recently in November last year, the Wikimedia Foundation defeated a gambling tycoon’s lawsuit in Munich, Germany. The German court sided with the encyclopedia over its refusal to censor his name in a Wikipedia article about the tycoon’s business.

In fact, this isn’t even the first time that petitions have alleged defamation by Wikipedia articles in India. Back in 2022, the Supreme Court refused to entertain a PIL filed by the Ayurvedic Medicine Manufacturers Organisation of India alleging that an article on Wikipedia was defamatory against the organisation.

“You can edit the Wikipedia article,” the court had only remarked then.

The stakes are, therefore, high with the latest ANI case in India set to add to this already controversial discourse.

Wikipedia’s challenges in India add to a complex global pattern of legal challenges, Kazim Rizvi, founder of tech-policy think tank The Dialogue told ThePrint. He added that this case particularly highlights the tension between Wikipedia’s global collaborative model and local legal demands.

“The questions around Wikipedia’s architecture and intermediary protections also raise fundamental questions about the sustainability of crowd-sourced knowledge platforms. The case could establish new precedents for how digital platforms negotiate this balance, potentially influencing similar cases in South Asian economies and beyond,” Rizvi explained.

‘Palpably false’

For Wikimedia, the trouble began around February 2019, when it started including claims such as ANI video editors admitting to forging clips, and that ANI allegedly falsely blamed Muslims for the sexual assault and rape of two Kuki women during the 2023 Manipur violence.

ANI’s own suit hints at an edit war among users over its Wikipedia page, before the defamation suit was filed. In April this year, attempts were made to edit the page, to add “true and correct facts” about ANI. However, it alleges that these edits were reversed by the Wikimedia Foundation, acting through three of its anonymous editors, “to cause harm and damage the reputation” of ANI.

The news agency then began its legal action by issuing a cease and desist notice to the Wikimedia Foundation in June this year, asking them to refrain from publishing false, misleading, and defamatory content.

ANI’s suit now speaks about the “publication of palpably false and defamatory content…with the malicious intent of tarnishing the Plaintiff’s reputation, and to discredit its goodwill”.

The suit, seen by ThePrint, claims that Wikipedia removed edits that showed the “true and correct position, supported by trusted sources” on ANI’s Wikipedia page. The removed edits include clarifications that “there is no evidence the network (ANI) is linked to India’s government,” among other things.

The defamation suit now lists not just the Wikimedia Foundation, but also three Wikipedia page editors and users, recognised only through their usernames.

The Wikipedians

It is the ‘Wikipedians’ who keep oiling the online encyclopedia and contribute to it by editing its pages. Anybody can become a Wikipedian and make changes to articles, as long as the information is referenced citing reliable external sources, and is presented neutrally— like an encyclopedia.

When ANI’s defamation suit came up before the court on 20 August, the judge directed Wikipedia to disclose the details of the editors of the ANI page through its lawyers, within two weeks. This was done so that ANI’s defamation suit could be served on these editors as well, and they could file their responses to the plea.

However, when the Wikimedia Foundation did not disclose the details of the editors by the next date of hearing on 5 September, the court issued a contempt notice to the online encyclopedia.

A month later, on 19 September, the Wikimedia Foundation appealed against the 20 August order. It has been alleged that this disclosure order was passed without hearing the Wikimedia Foundation’s side, and without providing due reasons for passing the order. It also submitted that the judge had not considered whether a prima facie defamation case was made out by ANI, and whether ANI was even entitled to this disclosure.

Akash Karmakar, Partner at law firm Panag and Babu, said that while the court’s order is well within the limits of Indian intermediary guidelines, the court may instead look past the intermediary—that is Wikipedia— and trace the source of the libelous information if it intends to pursue the real perpetrator of this offence.

‘Nobody would want to be an editor’

“I can’t imagine they would reveal any names. That would set a terrible precedent,” a Wikipedian

The anxiety over Wikipedia’s future in India has reached the Wikipedians as well.

“I would personally hate to see Wikipedia get banned in India,” an editor at an India-related noticeboard wrote. These noticeboards are public administrative pages where editors can discuss issues related to Wikipedia articles.

Another editor expressed their worries about the revelation of the potential page editors, saying, “I can’t imagine they would reveal any names. That would set a terrible precedent. They haven’t revealed no names before. (sic)”

Choudhary explained that the Wikipedia community has always been allowed to use pseudonyms or real names to become editors, and that all information is based on secondary sources. Volunteers discuss, debate, and often disagree until a shared consensus can be reached on what content to include on Wikipedia, and the entire process is out in the open, she pointed out.

“Every edit can be seen in the article’s history, and every discussion point can be seen in the article’s talk page,” Choudhary told ThePrint.

As per the Wikimedia Foundation, India contributes to one of the highest number of views of Wikipedia in the world, with about one billion page views per month. India also has the third-largest number of content contributors to English Wikipedia after the US and the UK.

Referring to such statistics, Choudhary said, “This is important for us and the editors. If each time an editor will be dragged to court by aggrieved, rich parties, nobody will want to be an editor.”

Rizvi also said that the Wikimedia Foundation does not operate like a traditional news agency or a social media platform. However, he asserted that Wikipedia’s editors require a degree of protection as they provide verifiable facts from either side.

He said that disclosing the identity of Wikipedia volunteers or editors “risks undermining Wikipedia’s neutrality and content quality, as contributors may self-censor to avoid backlash, leading to biased or incomplete information”.

Such a move, he added, would threaten the right to access information, a fundamental aspect of free expression under Article 19 of the Indian Constitution, as volunteers play a crucial role in ensuring diverse and verifiable content.

Also read: Working at India Post means being a multitasker—Chase new accounts, sell Gangajal, flags

The safe harbour

So, whose content is it anyway?

Or rather, whose responsibility is it, when Wikipedia only hosts content, with references to other sources?

The suit has also raised significant questions about third-party sources. At the end of the day, Wikipedia is a mere platform that hosts content added by anonymous editors, relying on third-party sources.

The Information Technology Act 2000 has ensured that India has a ‘safe harbour’ regime for online platforms, which provides them exemption from liability for third-party data.

However, ANI alleged that the Wikimedia Foundation’s conduct has resulted in a loss of its safe-harbor protection under Section 79 of the 2000 Act. This, it said, is because Wikipedia actively removed the edits that sought to reserve the allegedly false and misleading content against ANI— hinting at editorial control over the content.

Karmakar said that from the early 2000s, a digital conduit for information was not held liable for the information that it carried.

However, in 2021, the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 flipped this paradigm—causing intermediaries to have to undertake onerous compliance obligations to be able to qualify for safe harbor, he said. In fact, Wikimedia Foundation had even criticised a prior version of these draft rules, saying that the proposed changes “may have serious impact on Wikipedia’s open editing model…and have the potential to limit free expression rights for internet users across the country”.

These rules have now come in handy for ANI because the rules prescribe that intermediaries must refrain from hosting, storing or publishing any unlawful information on their platform, which is broadly defined to also include defamatory content and something that causes contempt of court. This law also mandates that intermediaries take down and disable access to such information as early as possible, no later than 36 hours.

ANI’s suit, therefore, asks Wikipedia to perform its obligations as an intermediary in accordance with the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021, and take down the false and misleading information on the ANI page.

The suit would, therefore, also contribute to the discourse over the role of the intermediaries in the digital ecosystem— a subject that has been of interest to policy-makers across the world, owing to the growing all-pervasive nature of technology.

The ransom

“If this power is used by other authorities in India to harass the publishers of factually accurate content that causes embarrassment, but is not defamatory, it would be a gross abuse of discretionary power to censor free speech,” said Akash Karmakar

The biggest blow to Wikipedia came during the 5 September hearing, when Justice Navin Chawla reprimanded the online encyclopedia for failing to comply with an order to disclose details of its page editors.

“We will close your business transactions here. We will ask the government to block Wikipedia,” he warned.

According to Karmakar, as a responsible business operating in India, Wikipedia is duty-bound to follow due process and comply with a court’s directive, irrespective of whether it agrees with the directive.

“While we debate the righteousness of holding safe harbour ransom, an intermediary would be forced to comply with the directives of Indian courts and government authorities,” he added.

Karmakar said that Wikipedia can be forced to disclose the IP addresses of the editors of the page. This, he said, is made possible by the 2021 Intermediary Guidelines, and a court or government agency that is lawfully authorised to conduct investigative or protective or cyber security activities, for the purposes of verification of identity, or the prevention, detection, investigation, or prosecution, of offences can ask for this information.

He explained that by going after authors of information that is intended to be factual, “Indian courts are sending a clear message to perpetrators of false news – that they would be exposed, and hunted down”. Karmakar calls it a “balancing power to force transparency”, where this follows due process and is used to engage in source-tracing of false news.

“However, if this power is used by other authorities in India to harass the publishers of factually accurate content that causes embarrassment, but is not defamatory, it would be a gross abuse of discretionary power to censor free speech,” he added.

ThePrint reached out to ANI’s lawyer, advocate Siddhant Kumar on call, but he refused to comment on the ongoing litigation. ThePrint also reached out to Wikipedia’s lawyers, advocates Aayush Marwah and Abhi Udai Singh Gautam through email, but hadn’t received a response till the publication of the article.

A fresh soup

ANI’s defamation suit has since opened the proverbial pandora’s box, with the questions it has already thrown at legal and tech policy experts.

During the hearing of Wikimedia’s appeal against the disclosure order, a two-judge bench of the Delhi High Court was informed about a dedicated Wikipedia page on the ongoing defamation suit.

ANI’s lawyers told the court, that the single judge’s order in the defamation suit has been “adversely commented upon” on the page. Citing other sources, the page had criticised the high court order directing revelation of the page editors, saying that it amounted to “censorship and a threat to the flow of information”.

This page on the defamation suit landed Wikipedia in a fresh soup with the High Court. The two-judge bench was of the prima facie view that these comments amount to “interference in court proceedings”, especially since the comments appeared on Wikipedia, which is the party in the suit.

In response, Wikipedia’s lawyers told the court that the Wikipedia page had not been created by the Wikimedia Foundation, which is the party in the defamation suit. However, the court directed the Wikimedia Foundation to take down the page within 36 hours, after finding that it prima facie amounts to “interference in Court proceedings and violation of the subjudice principle by a party to the proceeding and borders on contempt”.

Wikipedia then took down the entire article on the defamation lawsuit—the first English article in the encyclopedia’s history, according to news reports.

The reporter was not aware of the connection between Mishi Choudhary and Kabir Darshan Singh Choudhary, and the potential conflict of interest. The article has now been updated.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

Not sure which part of ANI being a government’s tool, the court doesn’t agree with. The final proof is the interview Mr. modi did with ANI. Now we know how many so-called-interviews he did during his tenure and their affiliations.

Wikipedia is highly biased. If they want free flow of information then disclose the name of editor for more transparency. Gives all sources of information rather than becoming propaganda outlet

Wikipedia, though a very useful tool to read up on something at a very basic level, is highly biased. One can surf through Wikipedia pages across topics, especially political and socio-cultural ones, to see the bias for themselves.

Nor is it objective, neither is it transparent. One can clearly see a pattern, kind of like an agenda, to push forth certain political viewpoints.

The fact that all contributors and editors hide behind usernames and cannot be identified is used as a tool to spread propaganda favouring certain political ideologies. And this includes fake news.

If Wikipedia wants to come across as objective and transparent, it must voluntarily make public the names (and educational/professional details) of the contributors and editors to an article.

Ms. Apoorva Mandhani is being clever with this article on Wikimedia vs ANI. A case of being too clever by half.

It is common knowledge that Wikipedia contributors and editors are avowedly Left leaning. As such, every single incident or issue is explained from a Left leaning perspective. One can easily spot the bias and favouritism across articles hosted on the platform. A glance through the Wikipedia page on RSS, BJP or even Modi clearly reveals its penchant for engaging in character assassination.

No wonder Ms. Mandhani loves Wikipedia.