Patna: Siyaram Saw hadn’t slept all night, dreading the microfinance recovery agent due at dawn. When the door finally rattled, the 48-year-old, paralysed on his left side, could only watch as the agent snarled, “I want the money today, whether you live or die,” family members recounted. Trapped and seeing no way out, Saw ended his own life that day.

This is no longer the old story of greedy sahukars. In Bihar’s new economy of debt, it is the corporate recovery agent who strikes fear. What ails India’s poorest state is a surge of microfinance companies and relentless lending, targeted primarily at women. Once saviours, they have become engines of debt, trapping families in the very loans meant to save them from poverty.

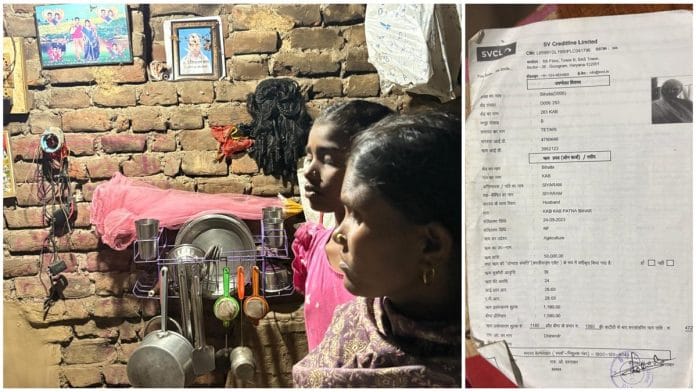

In Saw’s case, it was his wife, Tetari Devi, who had taken the loans.

“That agent came back. He saw my father trying to kill himself—he was still alive. He could have saved him,” recalled their daughter, Luchu Kumari, 20, cradling her four-month-old baby at their home in Kab village near Patna. “Instead, the agent ran and told the villagers that a man was taking his own life.”

With 150 microfinance companies operating in Bihar, the third-highest in India after Madhya Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, borrowing is easy, but debt often lurks around the corner. These lenders sell a dream of pucca houses, thriving businesses, and secure lives, but for many borrowers, it remains just that: a dream.

What started as a way of helping the poor to get out of the poverty line turned into a game of exploitation. It was like killing the golden goose to get all the gold at one point of time

-Rabi Narayan Mishra, RBI Chair Professor at Gokhale Institute of Politics & Economics

Across rural Bihar, families take multiple microfinance loans to cover daily expenses, then borrow again to meet weekly repayments. Many have reached breaking point. Some have died by suicide; others have abandoned their homes under cover of night. Left behind, elderly parents often shoulder the burden, facing threats, abuse, and constant intimidation. Loans and repayments have become permanent guests in their homes — a necessity for survival and a harbinger of ruin rolled into one.

Bihar is now India’s largest microfinance market, commanding 15 per cent of India’s total loan portfolio. And it also tops all states in both total debt and loan defaults. As of October 2025, total outstanding microfinance loans in the state stood at Rs 51,852 crore across 172 lakh accounts, with an average loan size of Rs 30,167, according to data shared with ThePrint by Sa-Dhan, a Reserve Bank of India-appointed self-regulatory body for microfinance institutions.

Of the 150 micro-lenders, 148 have a presence in rural Bihar, commanding a Rs 33,970 crore portfolio. Together, they serve 112 lakh rural clients, accounting for 65 per cent of the state’s total loan accounts. Behind these numbers are mostly women, who make up 95 per cent of borrowers nationwide, notes the Sa-Dhan Bharat Microfinance Report 2025.

There are two sides to the Bihar microfinance boom, which includes NBFC‑MFIs, banks, and small finance banks (SFBs).

One is apparent prosperity. Many say the sector has transformed rural Bihar over the past decade by supporting livelihoods and helping bring economic stability. When microfinance started taking off in the 2000s, even interest rates of 15-20 per cent were far lower than those charged by moneylenders.

“For the first 5 to 10 years, the model worked remarkably well. Though it operated alongside cooperative and regional rural banks, microfinance thrived because of its human touch—branch managers treated borrowers like family, travelled village to village on motorcycles, guided enterprises closely, and shared in the prosperity they helped create,” said Rabi Narayan Mishra, former executive director in charge of Bank Supervision and currently RBI Chair Professor at Gokhale Institute of Politics & Economics, Pune.

But over time, a diabolical debt spiral took root. It feeds on borrowers taking loans to pay off loans, and on recovery agents who are compelled to collect every rupee to meet the companies’ strict 100 per cent recovery targets.

“What started as a way of helping the poor to get out of the poverty line turned into a game of exploitation. It was like killing the golden goose to get all the gold at one point of time,” added Mishra.

ThePrint contacted Bihar government’s Finance and Rural Development ministries for comment through multiple emails, but received no response.

Also Read: Industries finally returning to Bihar—There is Britannia, Zara, Van Heusen and Adani

Pressure to collect

A narrow lane in Sakra is home to branches of at least three microfinance companies. Inside the RBL FinServe Limited (RFL) office, a man in his mid-20s sat in a spacious, nearly empty hall, typing on his laptop. He claimed to be the company’s youngest branch manager and said he had climbed the microfinance ladder unusually early.

“I started in the field, collecting repayments,” he said proudly. “Hard work and consistency got me here.”

RBL, like most microfinance institutions, offers two-year loans in partnership with a bank—in this case RBL Bank. Posters behind him promised “a better future”, especially for women, the sector’s primary borrowers.

Employees have daily targets [to get people to borrow]. If the target is Rs 5 lakh, they have to meet it. They go from person to person, giving out loans without considering whether the borrower can actually repay. The company puts a lot of pressure on them

-Sunil Kumar, former employee of a microfinance company.

On the ground, the reality often diverges from this language of empowerment. Borrowers, most with little formal education, are rarely armed with knowledge about fine print or avenues for relief.

The branch manager explained that while his company can negotiate settlements or grant extensions via a simple written request, most borrowers are unaware of these safety nets.

“They just come in a hurry to collect the money and leave,” he said. “People don’t have time to understand the rules or the full process.”

He insisted earnestly that his branch was “different” from others that “hound borrowers” for repayment, and spoke with sympathy for his rural clients.

“If someone genuinely doesn’t have the money, how can we expect them to pay? Giving a little extra time makes sense. And if, even after the extension, people still can’t repay, what can we do? Ultimately, the company bears the loss, but we don’t resort to coercion,” he said.

But the interest rates are often punitive. RBL charges 24.5 per cent interest on its two-year loans, with EMIs split across 24 months. Borrowers must complete e-KYC and submit Aadhaar, PAN, and bank documents to get the money. On a Rs 40,000 loan, the total repayment comes to roughly Rs 52,000 over two years. About Rs 12,000 is paid as interest. Nearly one-third of the loan amount goes toward interest.

One protection in the case of the borrower’s death is credit-linked life insurance. The RBL employee said that it’s optional but most borrowers do take it, usually in their own name or their spouse’s. If the insured borrower dies, the loan is supposed to be cleared. Once the documents are submitted, the insurance company pays the remaining principal and interest directly to the microfinance institution (MFI), and the loan is officially closed.

During this process, said the employee, MFI staff are prohibited from demanding repayments or harassing the family, in line with guidelines of the RBI and Microfinance Industry Network (MFIN). Any EMIs collected after the borrower’s death must be refunded to the nominee or legal heir once the claim is approved.

However, many families told ThePrint that recovery agents continued their pursuit even after the borrower’s death. For these employees, it’s about survival too. Many put in 12-15-hour workdays for salaries of just Rs 12,000-13,000 a month. To make a living wage, they rely on field allowances and incentives tied to collection targets.

“Employees have daily targets [to get people to borrow]. If the target is Rs 5 lakh, they have to meet it—there’s no way around it. They go from person to person, giving out loans without considering whether the borrower can actually repay. The company puts a lot of pressure on them,” said Sunil Kumar, a resident of Muzaffarpur who previously worked at a microfinance company.

“If they want to keep their job, agents have to meet these targets. To do that, they often pressure borrowers, and even when it comes to collections, the same intense pressure continues.”

The biggest price, though, is paid by borrowers, with many alleging harassment and even fraudulent practices.

Life under debt

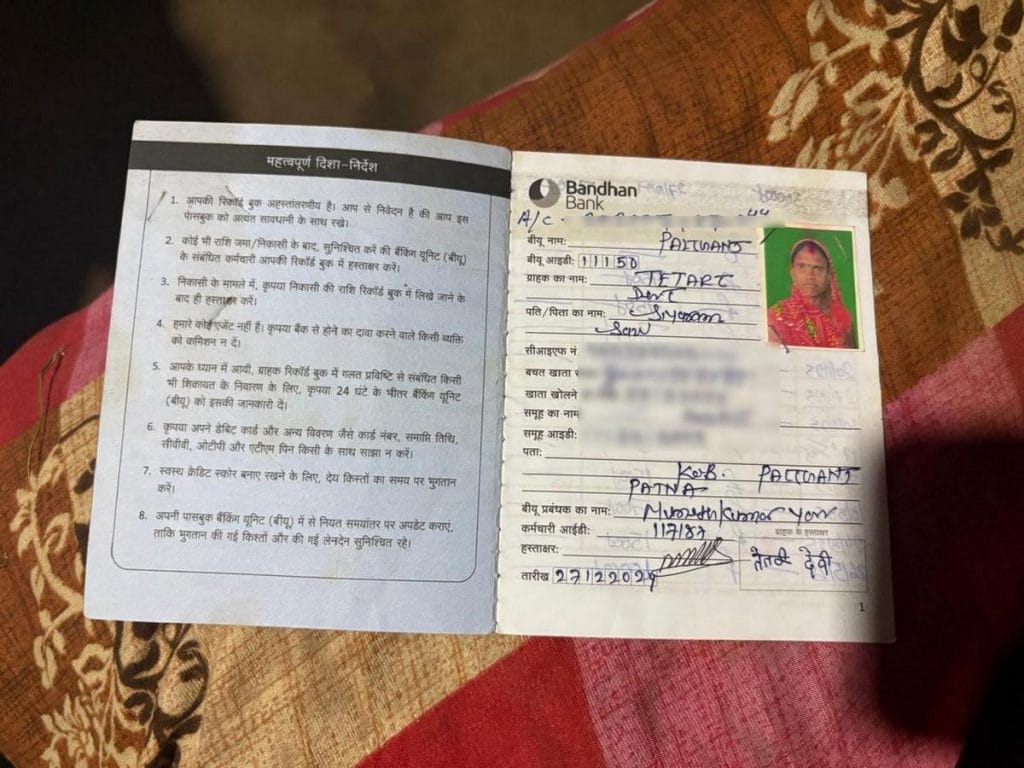

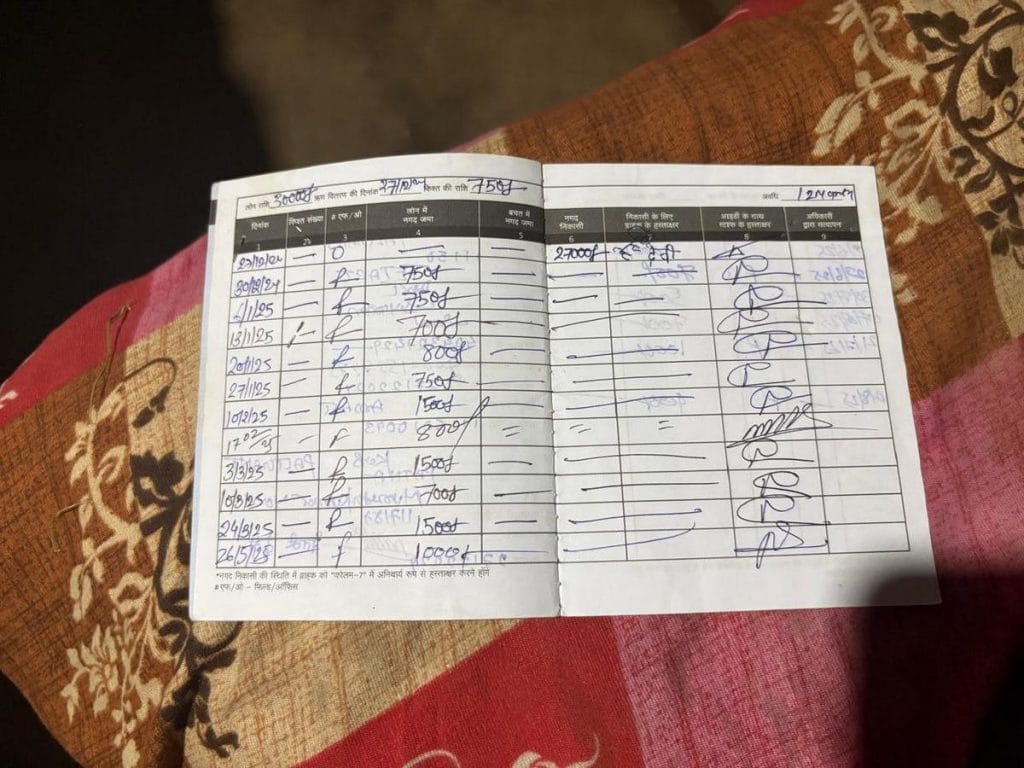

There was a time when life was different. Saw earned as a daily-wage worker in Mumbai. But after a stroke left him with partial paralysis and unable to work, he returned home to discover that his wife, Tetari Devi, had taken loans totalling around Rs 2 lakh from multiple microfinance companies—Fusion, Bandhan, and SVCL.

“I took the loan to get my daughter married, when my husband was away for work,” said Devi, 40, sitting in their single-room house. A photo of her husband hung on the wall, with a dried-up flower placed over it.

She managed to make the weekly repayments until Saw’s inability to earn made it impossible. The day before his death in August 2025, a recovery agent visited and verbally abused the family. That night, an argument between Saw and Devi escalated into a physical fight, leaving visible marks on her face.

Early the next morning, she left home and went door to door, begging for help to repay the loan, when villagers rushed to warn her: “Something has happened at your house, go quickly.”

She ran home to find her husband dead, surrounded by a whispering crowd and frantic hands attempting to take him down.

“It’s been months, and still no FIR, no post-mortem result. Even after everything, the company keeps sending agents demanding repayment. Nothing has ended,” said their daughter, Luchu Kumari, struggling to speak over the pounding DJ music from a neighbour’s wedding.

Police, however, offer a different account. Madan Jha, sub-inspector at Rani Talab (Kanpa) thana, claimed that the couple’s fight the night before had sent Saw over the edge.

“It wasn’t about the loans or the companies. Devi admitted that Saw had hit her and that they had fought the previous night,” he added, reading from the complaint letter held at the thana. “We registered the case under the UD [unnatural death] category. Investigation is ongoing. Tomorrow, I’ll collect the post-mortem report.”

Villagers, however, allege there is a pattern: whenever they approach the police about harassment from recovery agents, their pleas are routinely dismissed. Meena Tiwari, national president of the All India Progressive Women’s Association (AIPWA), agreed, noting that in her experience working on such cases, police rarely file FIRs against microfinance companies.

“Only a single case in Siwan district has ever been registered,” she said.

Forged documents and sacred vows

The double suicide of an elderly couple in Muzaffarpur’s Sakra Wazid exposed how fraud can grease the wheels of microfinance.

What shocked the village after 74-year-old Bhukli Devi’s death was the discovery that she had four Aadhaar cards. One listed her age as 51. Since microfinance companies cannot approve loans for those above 60, the other Aadhaar cards had been fabricated with a lower age.

Over time, Bhukli Devi had accumulated nearly Rs 3 lakh in loans from multiple microfinance companies. She and her husband, Shivnath Das, had initially borrowed the money like everybody else in their village.

They would come and pressure us to take more loans. If I had a Rs 10,000 loan and only Rs 5,000 left to repay, they would say, ‘We’ll waive your remaining Rs 5,000—just take another Rs 20,000 loan.’ We couldn’t understand the calculations; it felt to us like the loan had become smaller

-Asma Khatun, a resident of Muzaffarpur

“The money was spent on daily needs; when instalments became impossible to manage, they took another loan of around Rs 40,000, then one of Rs 60,000, then another of about Rs 1 lakh—until the debt reached Rs 3 lakh,” said Sita Devi, 55, a neighbour and a member of the same lending group.

Agents from various companies visited their home constantly, often late in the evening, demanding payments. Out of options, the couple left the village for several days. When they returned one early morning, they ended their lives on a peepal tree the villagers consider sacred.

“The agent had come that day too, but left when he didn’t find them. They would often talk about ending their lives,” said Sita Devi. That was nearly two years ago.

A police investigation confirmed that a microfinance worker had arranged a falsified Aadhaar card through an Aadhaar operator, according to a Dainik Bhaskar report. Both were arrested.

The pattern of exploitation takes other forms as well. Even paying off a loan doesn’t necessarily bring relief.

Fultmati, who migrated to Muzaffarpur from Deoria, said she had borrowed Rs 20,000 from one finance company and Rs 80,000 from another. When she fell behind on payments, agents allegedly seized her farmland. Harassed daily, she sold 52 decimals of land for Rs 95,000 to clear the debt. Even after repayment, she said one of the companies demanded her documents for “reverification” before closing her account.

Across Muzaffarpur and neighbouring districts, villagers describe a familiar cycle of escalating loans, relentless visits from agents, forced land sales, and families breaking apart.

In the case of Bhukli Devi, agents may have issued fake IDs to bypass the law, but used sacred oaths to facilitate repayment.

“Hum bhagwan ko sakshi manke ye loan le rhe hain aur shapath lete hain ki samay samay par lauta denge (We are taking this loan with God as our witness and pledge to repay it on time),” read the back page of one of her passbooks.

Mishra pointed out that the warning signs of the warping of microfinance were always visible and mirrored the trajectory of Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, which won Muhammad Yunus the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006, but within a few years was mired in controversy and even described as a “death trap for the poor”.

“Interest rates rose, multiple loans were pushed onto the same households, and RBI eventually had to intervene and cap lending rates. This is exactly what happened in Bangladesh. We should have learned the lesson from there,” he said. “I call it a historical boom and bust. The benefits rose very fast, then they had to fall one day. And then it will come back—but at a lower equilibrium.”

Pressure to borrow more

Asma Khatun from Muzaffarpur district has borrowed from seven different companies, with total loans crossing Rs 3 lakh. The sofa-making business she started has failed, but she still has to pay Rs 8,000 a month, which comprises nearly all of her monthly income.

This is far outside the boundaries set by RBI’s 2022 microfinance framework that specifies these loans are meant for low-income households earning up to Rs 3 lakh a year, and that monthly repayments cannot exceed 50 per cent of a household’s income.

In July 2024, the Microfinance Industry Network (MFIN), an RBI-approved self-regulatory body, introduced additional “guardrails” to check over-indebtedness: no more than four microfinance lenders per borrower, and a total exposure cap of Rs 2 lakh.

Khatun, however, said she was constantly induced to borrow more and more money.

“They would come and pressure us to take more loans. If I had a Rs 10,000 loan and only Rs 5,000 left to repay, they would say, ‘We’ll waive your remaining Rs 5,000—just take another Rs 20,000 loan.’ We couldn’t understand the calculations; it felt to us like the loan had become smaller,” she added,

Last year, Khatun recalled, an employee came demanding repayments. She wasn’t home, but her husband was. The agent took him around the village and ordered him to beg for money.

“He did that, and the shame of doing so was unbearable. One of our goats was taken when we couldn’t repay,” Khatun said, her eyes welling up.

That night, he didn’t eat, and only drank a cup of chai. After Khatun fell asleep, he hanged himself from the fan. The same day, she said, the agent returned, collected money from other group members, and left.

A solution to ‘remittance economy’?

In Patna, a house has been converted into a branch of Fusion Microfinance, with ledgers, loan files, and posters reading ‘Fusion ke saath aage badhe’ filling the cramped workspace. A woman rushed in to speak assistant branch manager Atul Raj as he juggled walk-ins, paperwork, and phone calls.

“I’ve been taking loans from here for the past two years. I repay on time, and the company is good, so it works out,” said the woman in her late 40s, before rushing out to catch an auto.

Interest rates at Fusion start at 23.9 per cent for first-time borrowers and reduce with timely repayment, with Axis Bank as its lending partner.

In regions like Bihar, where traditional banking penetration has historically lagged, microfinance has helped integrate many households into the credit and financial services network

-Sa-Dhan

The process here is tightly structured: customer data verification, house inspection by a Relationship Officer, document submission, then approval from the branch manager. Loans are typically disbursed within 24 hours. The company has been operating for over a decade and employs around 600 people across India. Official timings for staff are 8 am to 5:30 pm, mostly in the field.

Although Raj said that the company does not use pressure tactics, borrowers in several districts report visits at odd hours and humiliating language from collection agents.

Another major player is Sonata Finance, now part of Kotak Mahindra Bank, a well-known microfinance company whose name is familiar to most women in Bihar.

Its regional manager, asking not to be named, credited microfinance for transforming rural Bihar and for “nearly 90 per cent of homes” now being pucca, in sharp contrast to a decade ago.

For him, migration and microfinance are Bihar’s main prosperity drivers.

“People travelled outside, incomes rose, and poverty reduced,” he said. “Microfinance has played a major role in that shift.”

For Sa-Dhan, microfinance could give Bihar’s young population an impetus to stay in the state and try their hand at small enterprises.

“Currently, Bihar is heavily dependent on the remittance economy, as over 60 per cent of households have at least one member working outside the state,” said the institution in a written communication to ThePrint. “One of the core objectives of microfinance is to promote livelihood activities in low-income households. MFIs in Bihar are trying to close this gap by providing working capital to young people and supporting them in starting their own microenterprises.”

For now, there are few other options, with limited government support for loans.

Also Read: This is how Bihar’s Jeevika didis spent the govt’s Rs 10,000

The missing safety net

An elderly woman stepped out of her kachcha mud house in Paliganj village of Patna district, her back bent with age, goats trailing behind her. She had taken a loan for her son to start a business, but he had left for another state with his wife months ago and hadn’t returned.

“Now the loan collectors come to me, but I have nothing to give,” she said, gesturing toward her home.

For borrowers like her, government-backed credit options are few. The most prominent scheme is JEEViKA, launched in 2007 under the World Bank-supported Bihar Rural Livelihoods Project. The programme offers credit to rural women through self-help groups led by a sakhi and operates in 34,043 villages across all 534 blocks. Yet, its reach is narrower than the microfinance sector, which offers larger loans to far more low-income borrowers under looser eligibility criteria.

Despite having over 9 lakh SHGs and statewide coverage on paper, JEEViKA specifically targets “rural poor households” identified and endorsed by village organisations, linking membership to poverty and social inclusion criteria rather than open access. By contrast, under RBI’s 2022 framework, microfinance companies can lend to any household with annual income up to Rs 3 lakh. Within these limits, MFIs actively expand to all eligible low‑income households, not just the poorest or SHG‑affiliated women.

“In regions like Bihar, where traditional banking penetration has historically lagged, microfinance has helped integrate many households into the credit and financial services network,” said the written communication from Sa-Dhan. “A large share of loans (>90%) is used for income generation purposes, indicating these loans are reaching entrepreneurial or productive uses rather than just consumption.”

But desperation more than entrepreneurial drive is the fuel for the industry. While fewer people live in poverty today, Bihar still has the highest poverty rate in India at 33.76 per cent, according to the 2023 Niti Aayog index. Thirty-four per cent of families earn less than Rs 6,000 per month, and 64 per cent earn under Rs 10,000.

Ahead of the recent assembly elections, the state transferred Rs 10,000 to women’s bank accounts under the Mukhyamantri Mahila Rozgar Yojana, intended to support small self-employment activities. But in most households, the amount was quickly absorbed by basic expenses.

“Everyone received the money,” said Aruna Devi, a JEEViKA member. “But it was spent on daily needs.”

Activist Meena Tiwari added that other schemes such as the Laghu Udyami Yojana, meant to finance starting small businesses, reach only a limited number of applicants, usually those with connections.

Last year, the Chief Minister once announced assistance of Rs 2 lakh for 94 lakh low-income families to help them begin self-employment ventures but this too has become tangled in paperwork, according to Tiwari.

“Beneficiaries struggled to obtain the required income certificates, and even those who managed to secure the documentation say they never received any funds. The scheme, they claim, exists only on paper,” she added.

Tiwari said that despite rising complaints, there is no state-level mechanism to regulate microfinance operations in Bihar. The RBI issues guidelines, but enforcement remains largely voluntary, leaving borrowers vulnerable and with few avenues for redress.

Some steps, though, have been taken by Sa-Dhan to address over-indebtedness and repayment stress. In 2024, it introduced the ‘Sankalp’ guidelines, revised this year, which set limits on the number of lenders per household, caps on combined microfinance and retail exposure, mandatory credit bureau checks, transparent pricing, repayment discipline, and employee verification to reduce fraud.

The organisation also works closely with district officials, police, RBI regional offices, NABARD, local politicians, and panchayat bodies to resolve disputes. But there’s only so much it can do and thousands of families continue to wait for justice, making repeated trips to police stations. And in some cases, the burden gets handed down to the next generation.

After Saw’s death, Tetari Devi’s youngest son, 14-year-old Sandeep Kumar, left for Delhi to find work, determined to support his family and repay their debts.

“He works in a mill, earning Rs 10,000-12,000 a month,” said Devi. “He sends Rs 3,000 home to support the family in Bihar. He says, ‘Maa, I will pay off the entire loan.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)