Ara: In Ara’s Babu Bazar, one of the town’s old zamindar houses has found a new lease of life. Within its weathered walls now runs a Motilal Oswal franchise, the 104th trading office the company has opened across Bihar.

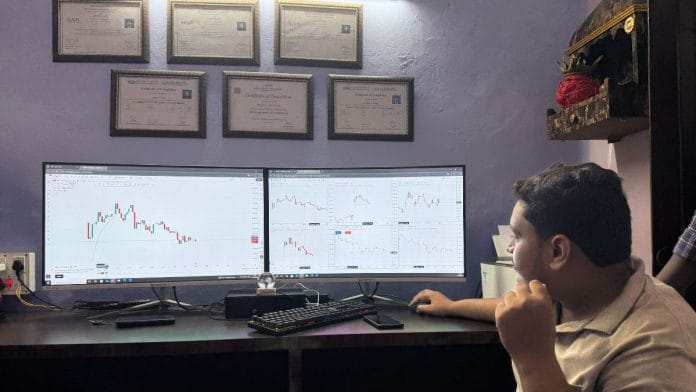

Inside, two Zebronics Pure Pixel screens glow in the half-light. On the wall behind them hang six framed certificates, each bearing the names of Rahul Kumar (23) and Priyanshu Kumar (23), affirming their credentials from SEBI’s Investor Certification Examination and the National Institute of Securities Markets.

This office has been serving nearly a hundred stock market investors in Ara since 2023, when the two Gen Z partners set it up with backing from Motilal Oswal’s Patna headquarters.

Among Rahul and Priyanshu’s clients are a government clerk, a seller of imitation jewellery, a quack doctor, a factory supervisor, and the owner of a sweet shop. These names, however, account for only a sliver of the town’s true investment story. Just a handful turn to the duo for help in untangling the stock market’s jargon.

The majority trade on their own, swiping through apps like Zerodha, Angel One, Upstox, or Groww, wherever they happen to be. Many aren’t even in Ara anymore—they are students in hostels, or workers scattered across India—but their Aadhaar-linked identities still tether them to Ara, and to Bihar.

Between FY 2020 and August 2025, Bihar saw an astonishing 715 per cent leap in stock market participation—rising from 6.7 lakh to 54.6 lakh investors. This is the sharpest surge recorded by any state in that period, equivalent to a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 52.8 per cent.

Data from the Association of Mutual Funds in India (AMFI) shows that nearly 89 per cent of Bihar’s mutual fund assets are invested in equity schemes. The pattern is striking: the state now counts more equity-driven investors than several wealthier peers, including Delhi and Punjab.

Bihar today ranks tenth on the National Stock Exchange’s roll of states with the highest number of unique registered investors. That a state with one of India’s lowest per capita incomes—barely ₹60,000 a year—should place itself in this league has startled many observers.

Bihar’s stock market boom reflects how technology, rising financial literacy, and a restless hunger for mobility are remapping its economy. For a state long synonymous with poverty and migration, the act of millions opening trading accounts speaks of an emerging aspiration. It reflects a collective decision to stake a claim in India’s growth story rather than stand at its margins.

That so many in Bihar are now willing to put their modest savings into equities also suggests a changing psychology in the state. People are today ready to take risks for higher returns, a sign of confidence in both the markets and their own future.

During cricket matches, Sachin Tendulkar—the god of cricket—would appear in ads, urging us to invest in mutual funds. For years, that warning in his voice—‘Mutual funds are subject to market risk’—kept echoing in my mind.

—Ajay Kumar, B.Sc. Chemistry graduate

The same digital rails that carried Bihar into India’s payments revolution are now making investment accessible. With smartphones and apps as conduits, geography matters less; opportunity can be tapped even from small towns and villages.

“Even though Bihar’s per capita income has only risen modestly, a state with more than 14 crore people can still generate massive participation,” said Dr. Rana Singh, Dean (Academics) and Director at Chandragupt Institute of Management, Patna (CIMP). “A mere 10per cent rise would mean 1.4 crore new investors.”

Though technology has unlocked opportunities across India, Dr. Singh noted that its impact is especially striking in Bihar: “What was once a complicated and cumbersome way of entering the stock market has now been simplified through banking apps, UPI, and mobile platforms.”

Also read: Patna is now a city of museums. Making its history great again

Building trust, one call at a time

Tucked away in a quiet residential lane of Ara, the Motilal Oswal franchise is an outlier of sorts. Inside, it is only a small wooden-floored room; outside, however, hoardings proclaim it to be “a one-stop solution for all your financial needs,” setting it apart from the homes around it.

At nine a.m. sharp, Rahul Kumar and Priyanshu Kumar meet here and quickly get on their phones. They scan stock charts, flip through the news, and call clients in the middle of their workdays, giving them advice on which stocks to buy. Between commissions on these tips, portfolio management fees, and their own trading, they say they earn about ₹1 lakh a month.

Rahul and Priyanshu, both B.Sc. Mathematics graduates from a local college, first dipped into the stock market as retail investors, making modest profits on their own trades before learning how to earn commissions and establish themselves as traders.

Ajay, Rahul, and Priyanshu—all emblematic of Gen Z—have veered away from Bihar’s long-held dream of a secure government job in the railways, SSC, BPSC, or even UPSC. Instead, they are chasing stocks.

To qualify as brokers, the two men first cleared a mandatory six-month foundational course from the All India Institute of Stock Market (AISM). Alongside this, they also had to pass the exam conducted by the National Institute of Securities Markets (NISM) to be recognised as legally eligible financial experts.

“I had already cleared my basics by watching YouTube channels like Power of Stocks, Stock Burner, Pushkar Raj Thakur, and Prabhat Trading Service,” said Rahul. What struck him most was that these channels were run by young men much like himself. Most of them, he saw, were not from financial capitals like Mumbai or Bengaluru, but from small towns across Gujarat.

Alongside this tech-savvy duo works 52-year-old Vikas Kumar, once an insurance agent with Reliance and the LIC.

Every evening, Vikas rides his bike through Ara, stopping for tea and conversation, reviving old ties from his insurance days. Those relationships now help him guide people through the shift from fixed deposits and LIC policies to stock market investing.

“The real work happens on our phones,” he said. “We need a physical office only to build trust. Investors must know there is a place they can barge into when things go wrong.”

Vikas was also quick to draw a contrast with the past: “It’s not like the earlier batch of agents who ran off with lakhs and crores in the name of life insurance. Now, with real-time updates on apps and agents like us, that trust deficit is being rebuilt.”

Also read: Patna to London—A Bihar ex-IAS has taken crossword to new heights

Ara’s ‘zero to hero’ dreams

In Ara, Rahul, Priyanshu, and Vikas together service about 100 demat accounts. Of these, 80 comprise active investors who regularly buy and sell stocks or maintain running SIPs. Among them, about 50 are middle-aged, self-employed, or salaried individuals who trade with caution, while 30 belong to Gen Z.

Gen Z, Rahul said, is far more reckless and daring: “They usually trade with less than a lakh in hand, but they chase quick profits.”

In 2019, Ajay Kumar was still in Class 10 when he decided to invest ₹10,000 of his pocket money. Using his brother’s PAN card, he opened an account on Angel One, a mobile brokerage app.

“I began with tips from Instagram reels and YouTube. I wanted to make quick money,” Ajay recalled. He lost the entire sum. A second attempt—with another ₹10,000—met the same fate.

Chastened, Ajay gave up. But around him, Ara was just beginning to stir awake to the stock market. Then came the lockdown of 2020, when the world shrank into screens and the internet became everyone’s lifeline.

“During cricket matches, Sachin Tendulkar—the god of cricket—would appear in ads, urging us to invest in mutual funds,” said Kumar, now a B.Sc. Chemistry graduate.

“For years, that warning in his voice—‘Mutual funds are subject to market risk’—kept echoing in my mind.”

By then, bank accounts opened under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) were being linked to PAN cards at scale, pulling millions into the formal financial system.

Pop culture, too, was shifting in tandem. Advertisements, web series, and a flood of finfluencers on Instagram began to seed trust in mutual funds, particularly among young men.

Hansal Mehta’s Scam 1992 (2020) might have been a cautionary tale against unscrupulous profiteering, but the SonyLIV series ended up igniting an explosion of everyday investors.

Around the same time, the phrase ‘zero to hero trade’ began to circulate in the stock market lexicon, capturing the thrill of turning ten rupees into a hundred.

In Ara, as in hostels and classrooms outside Bihar, Gen Z had started speaking this new language fluently. Charts, candlesticks, SIPs, and stocks all became part of everyday conversation.

Also read: Patna Planetarium is on top of its game today. An IAS officer sparked the transformation

Chasing stocks, not sarkari jobs

Young investors in Ara are trying, failing, and then trying again until they find a rhythm in the market.

After two failed attempts, Ajay finally turned to Rahul and Priyanshu for guidance.

“When he came to us a year ago, he already had demat accounts with Zerodha, Kotak Securities, and Angel One,” Rahul recalled. “We helped him open one with us, too.”

This third attempt again began with ₹10,000, but this time Ajay relied on Rahul and Priyanshu’s stock tips—mostly small- and mid-cap picks. Soon he ventured into futures and options, where his profits doubled. Within six months, that initial ₹10,000 had grown into ₹50,000. His portfolio today holds a ₹2,000 SIP and about ₹15,000 in mutual funds. The rest has been spent.

The below-30 generation is spending aggressively, and that money has to come from somewhere. In the absence of legitimate income, many are turning to the stock market for quick money. It’s this investment that is sustaining their lifestyle.

—Rajendra N. Paramanik, Assistant Professor of Economics and Finance, IIT Patna

“Usually it’s the latest bike, the next iPhone model, or a trip inspired by some viral reel,” Rahul said, admitting that a similar thrill drives him, too.

For Ajay and his peers, trading is not just about building capital; it is about how they fund and sustain their lifestyles.

Ajay, Rahul, and Priyanshu—all emblematic of Gen Z—have veered away from Bihar’s long-held dream of a secure government job in the railways, SSC, BPSC, or even UPSC. Instead, they are chasing stocks.

“This career of financial advisor didn’t even exist for us a few years ago, but I’m trying to become one now,” said Ajay, who met Rahul and Priyanshu in 2024 and was inspired by their trajectory to try the same path.

Opportunities, he added, are plentiful—from brokerages like IIFL Securities to FMC India and Sharekhan by BNP Paribas, all of which now have a strong presence in small-town Bihar.

Interestingly, Ara has investors even younger than Ajay. Eighteen-year-old Om Prakash runs a ₹7,000 SIP, while Mohit maintains a modest ₹2,000 one, adding to it whenever pocket money permits.

Also read: Leopards & snakes in Gurugram, Ghaziabad? Two NCR wildlife superheroes on speed dial

Demographic dividend or looming liability?

Nearly 58per cent of Bihar’s population is under 30. Many of them are ambitious, internet-savvy, and eager to look beyond conventional jobs to secure their future. SIPs, in particular, have let them start with as little as Rs 100, a sum modest enough to limit risk yet steady enough to build confidence over time.

“Last year’s data shows that a growing number of youngsters are entering the stock market. But this isn’t capital-driven growth, it’s consumption-led,” explained Rajendra N. Paramanik, Assistant Professor of Economics and Finance at IIT Patna. He linked Bihar’s stock market boom squarely to young investors.

For Paramanik, the state’s demographic dividend is both an asset and a risk.

“That same profile could become a liability 20 years from now if not redirected constructively,” he cautioned.

In Ara, the faith once reserved for gold jewellery is slowly being redirected to stocks, as younger family members persuade women to lend their identity cards for a new kind of investment.

“The below-30 generation is spending aggressively, and that money has to come from somewhere. In the absence of legitimate income, many are turning to the stock market for quick money. It’s this investment that is sustaining their lifestyle.”

Pramanik observed that the profile of young investors reveals an attitude driven more by aspiration than by accumulation.

“They’re not intent on building capital,” he said. “What they seek instead recalls the 1990s American dream, where a house, a backyard, a dog, and a car came to symbolise a flamboyant lifestyle. That is the aspiration now.”

The internet’s penetration and the visibility of a few success stories, Pramanik noted, have only amplified the trend. According to him, the risks are sharpest in the derivatives market, where only a miniscule fraction of investors succeed.

“Nearly 70 percent of those under 30 who ventured here have faced losses,” said Pramanik. The pattern, he warned, is unsustainable.

“If this continues, it could lead to debt-driven or consumption-driven growth—neither of which is healthy in the long run.”

Also read: Who is really running Nagpur & Mumbai? Influencers, proxy corporators, not civic council

Trading in her name

In Ara, the faith once reserved for gold jewellery is slowly being redirected to stocks, as younger family members persuade women to lend their identity cards for a new kind of investment.

Many Motilal Oswal and other brokerage franchises are registered in women’s names, but the day-to-day trading is handled by men. Demat accounts in women’s names often end up being run by younger male relatives—some barely out of school—perpetually tethered to their phones.

“My homemaker sisters also have demat accounts,” Ajay admitted, though it is the men in the family who actually run them. “Their husbands convinced them not to buy gold jewellery, but to put money in mutual funds instead.”

Beyond these men trading in women’s names, however, there are some investors like Suman Kumari, who grasped quickly that the market was changing. An ASO in the Patna Secretariat, she began a running SIP of ₹10,000 in 2023.

“It is an important capital-building exercise,” Kumari said.

While Patna still accounts for the largest pool of investors, the base has steadily widened beyond the city’s middle and upper-middle classes. Smaller semi-rural towns, meanwhile, have begun to show remarkable growth.

With long work hours and household responsibilities, she didn’t have the time to manage her portfolio herself. That’s when Rahul and Priyanshu stepped in.

“At least mutual funds are transparent,” she added. “There is real-time data to cross-check whatever tips my brokers give me.”

If Kumari relies on advisers to steady her investments, others like Suman Rungta prefer to rely on no one but themselves. Rungta, 50, runs a ladies’ garment shop in Patna. Behind the counter, she is also quietly piecing together a portfolio in the stock market.

Rungta began investing in 2019, encouraged at first by her husband’s interest in equities, though she was determined to make her own choices. A diploma-holder in computer science and once an IAS aspirant, the entrepreneur saw in the markets a way to take control of her savings.

“I use my knowledge and do it entirely on my own,” she said.

What Rungta wanted was growth without recklessness.

“I wanted my spare money to grow, but safely. So I taught myself to read charts and study companies before buying into anyone’s tips,” she added. Today, her portfolio stands at ₹10 lakh.

Also read: Bengaluru to Palghar, potholes are a death trap. AI startups racing to solve it

Bihar’s new investor geography

Jitendra Kumar, 38, heads IIFL’s Gandhi Maidan franchise in Patna, leading a team of four. For fifteen years, he worked across brokerage firms in different roles before opening his own franchise. Today, he manages portfolios for over 1,200 clients.

“At these centres, it’s mostly older customers who have shifted from FDs and LICs,” he explained. “But behind the portfolios on apps like Zerodha, Angel One, Upstox, and Groww are young minds, many of them juggling multiple demat accounts, sometimes as many as ten.”

Narender Kumar, branch manager at Motilal Oswal, oversees multiple franchises across Bihar. Before opening his own outlet at Patna’s Dak Bungalow Chauraha in 2020, he spent five years with the firm in Ranchi. With over 13 years in the stock market, Kumar watched investor interest surge after the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Two waves came—one from Gen Z and another from the business community,” said the 38-year-old Narender. “The Gen Z wave ended by 2023. They came for quick trades with minimal capital, but the business community stayed on as our core base.”

Explaining the stock market’s appeal, Narender said he often reminds his 5,500 clients that unlike running a business, investing demands no staff or daily management.

“With mutual funds and equities, your money itself does the work,” he tells them.

Earlier in Bihar, Narender recalled, people had little beyond Sahara schemes or the post office.

“How could we expect large numbers to travel all the way to Patna and become stock market players?” he asked. “Bihar once had one of the country’s oldest regional exchanges—the Magadh Stock Exchange, set up in 1985—but it shut down long ago, in 2007.”

While Patna still accounts for the largest pool of investors, the base has steadily widened beyond the city’s middle and upper-middle classes. Smaller semi-rural towns, meanwhile, have begun to show remarkable growth.

Narender and his team of seven often travel to small towns and rural outposts, hosting high teas and running investor awareness programmes to widen their base. This is a territory that their rivals, too, are eager to capture.

“It’s in these one-on-one meetings that trust takes root,” he said. “Within two conversations, we can usually guide people from conventional savings to the stock market.”

Also read: World Baniya Forum wants to mentor the next Adani, Ambani. Post-1991 India is about hustle

Small towns, big bets

In Bihar’s brokerage landscape, Motilal Oswal now ranks fourth, trailing app-based giants like Zerodha, Angel One, and Groww.

Vishek Chauhan, a businessman from Purnea who runs a school, a café, and a cinema, also dabbles in the stock market. He estimates that traditional brokerages now account for no more than 30 percent of investors.

“The remaining 70 percent comes through brokerage apps. Apps like Zerodha, for instance, smashed the old commission-based system and made it possible to invest with whatever small-ticket money one had,” he said.

Chauhan himself turned investor in 2020. Trading calls from financial consultants soon flooded his phone, urging him to buy one stock, then telling another batch of investors to sell the same.

“They profit from whichever side wins,” he recalled.

The experience soured him on brokers, and he turned instead to YouTube tutorials. After early losses, he settled into a more patient ‘buy and forget’ strategy. His portfolio is now worth around ₹25 lakh.

Back in Ara, Rahul Kumar has seen enough to know that the market has its own way of humbling newcomers.

“Some of our clients were trying to trade on their own,” he recalled. “They watched YouTube videos, learnt a bit here and there, but after losing two or three times, they finally came to us.”

For Rahul, such cases are a reminder that while the internet has armed a generation with tutorials and trading apps, it has also made them more vulnerable to easy mistakes.

“We are experts,” he said, stressing the years of training and certification from NISM and other institutions. “Our role is to minimise their losses, to guide them toward safer instruments like SIPs and mutual funds.”

The competition from discount brokerages like Zerodha and Groww is undeniable. Their appeal, Rahul admitted, lies in convenience and low cost.

“It’s like D-Mart offering a buy-one-get-one offer,” he said. “Of course, people will go there. But then there are premium franchises like Motilal Oswal. Both will run parallelly. We can’t say everyone will shift one way or the other.”

Rahul Kumar is the firstborn of Vijay Kumar, 56, an electric shop owner.

“I never allowed my sons to visit my shop because I wanted them to get government jobs. A job in the defence sector would have been ideal,” said Kumar, who had daily earnings of Rs 500.

For years, his son kept his plans to become a mutual fund advisor hidden from him. It was only in 2022, when the job started paying back, and he made a Rs 20,000 profit, that he finally spoke about it. It took several months to convince his father that mutual funds function like banks.

“Once I took him to a local branch and made him speak to an employee, who explained the process of the stock market,” Rahul shared. After that, his father was assured that he hadn’t fallen for a scam.

With the money he now earns, Rahul has retired his father from the electric shop, is repaying a personal loan taken years ago, arranged the marriage of one of his bua’s (father’s sister’s), paid for medical expenses for his father’s ailments, and is funding his younger brother’s education at an ITI in Patna.

For his mother, Madhuri Devi, a matriculate, it was a struggle to understand the nature of his work. But over time, she has learned to tell relatives with a certain pride that her son is a financial advisor.

The article is part of a series called ‘Changing Bihar‘.

(Edited by Shreevatsa Nevatia)

I am glad that this article talks about the downside of this as well.

I am happy that people are getting access to participate in stock market but when you trade in futures, it’s a whole different game.

Financial literacy is being improved but it’s still not holistic in nature. People need to learn that most people who trade in futures are going to lose.

Thank you very much that you came to Bihar and tried to highlight all these things.