Begusarai/Patna: A new uprising has found its epicentre in Begusarai, the former ‘Leningrad of Bihar’ turned BJP stronghold. The fight isn’t about ideology but the identity of one of the state’s dominant castes, the Bhumihars. They want to undo a 2015 clerical error and return to the British Raj-given status they held 95 years ago as Bhumihar-Brahmins. It is, in some ways, a reverse anti-colonisation endeavour.

At the heart of this Bhumihar reckoning is one question: Who are we?

At an informal village chaupal in Bihat, a village in Begusarai, known as Mini Moscow for its leftist fervour, 26-year-old Vikram Singh raised the community’s rallying cry as 25 villagers applauded — Brahmin Jaati Bahaal Karo. Restore Brahmin caste.

This chant is ringing out among Bhumihars across Bihar. What they want is a return to the nomenclature used in the 1931 caste census, which classified them as Bhumihar Brahmins, setting them apart as Brahmins who took to agriculture and landownership. Over the past decade, however, just “Bhumihar” has prevailed in official documents after the Savarna Ayog, Bihar’s Commission for Upper Castes, used the term in its 2015 report.

Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s caste survey in Bihar and ambitious land records digitisation have set off a wave of Bhumihar anxiety. The community wants to settle the question of its official name before the upcoming national caste census, which would be the first such exercise since the British counted caste nearly a century ago. Losing the hard-fought and coveted Bhumihar-Brahmin tag could affect their higher-caste status in an irreversible manner. Time is running out.

“The Bhumihars will no longer be defined by anyone else’s terms. The nomenclature change has left many of us feeling like strangers in our own land,” said Singh in smoke-filled Bihat, part of the Barauni-Begusarai industrial belt. “It’s the defining moment for us. Our ancestors were warriors, scholars and farmers. If we let this opportunity slip away, the identity of the Bhumihar Brahmin community will be lost forever.”

The caste survey has triggered fears of historical erasure and resulted in a flurry of petitions, politics, and protests demanding the government reinstate the term Babhan (Bhumihar Brahmin) in official records and caste certificates.

We still dominate Bihar politics. Hum ginti mein kam hain iska matlab ye nahi hai ki hum kamzor hain” (Just because we are few in number doesn’t mean we are weak)

-Surya Singh, Bihat resident

The Savarna Ayog office desks in Patna have piles of petitions stacked up. Many of these rely on two legacies — British caste census records and a lineage that goes back to Parshurama, a warrior sage.

The clash exposes a deeper crisis of caste in contemporary Bihar, where shrinking power, economic anxiety and the politics of enumeration are reshaping how a community sees its past and negotiates its future.

The Bhumihar identity has always lived under a cloud of confusion. The British gave Brahmin status to eastern Uttar Pradesh Bhumihars, but in Bihar they were still placed under the Vaishya category until the late 1800s. It was only after they mobilised and lobbied, much as they are doing now, that they got the Brahmin tag from the colonial rulers.

Colonial surveyors of the 19th century classified them in varied ways. Francis Buchanan-Hamilton called them “Military Brahmins”. William Adam termed them “Magadh Brahman”. William Crooke, in Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh, mentioned them as Babhan, Zamindar Brahman, Grihastha Brahman, and Pachchima (western Brahmans). Later sociologists and ethnographic studies described them as a land-owning agrarian elite and ayachak (non-begging) Brahmins. They currently make up 2.87 percent of Bihar’s population, according to the caste survey.

“They are a cultivating caste with a significant population in eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. They have Brahminical roots, but the fixing of their caste identity was done during the British caste census,” said Anand Teltumbde, scholar and author of The Caste Con Census (2025). “At that time, they were a local caste. The caste census formalised them into a dominant caste.”

The “catalysation” among the community for their identity resulted in the making of several caste-based sabhas, which “awakened consciousness”, according to Teltumbde.

“That time, castes wanted to be included in higher hierarchies in contrast to current times,” he added.

Also Read: A Ranchi boy reading at a petrol pump went viral. What came next

A legal fight

When the Bihar government released its caste survey report in October 2023, Dhirendra Kumar, a Patna-based TV journalist, was furious. His community was classified simply as ‘Bhumihar’— without the suffix that put them on the top tier of the caste hierarchy. Within weeks, Kumar moved the Patna High Court with a petition to change the nomenclature to Bhumihar Brahmin.

Kumar is from Jehanabad, which saw the emergence of Ranvir Sena, a fierce Bhumihar militia that was formed in the 1990s to assert dominance through force. But times have changed. The battlefield has moved from villages to courts. His petition created a buzz across the state.

“The whole matter started with our petition. We moved to the court with earlier land record documents and the British census reports which mentioned our caste correctly,” said Kumar at the News4Nation newsroom in Patna’s Kidwaipuri.

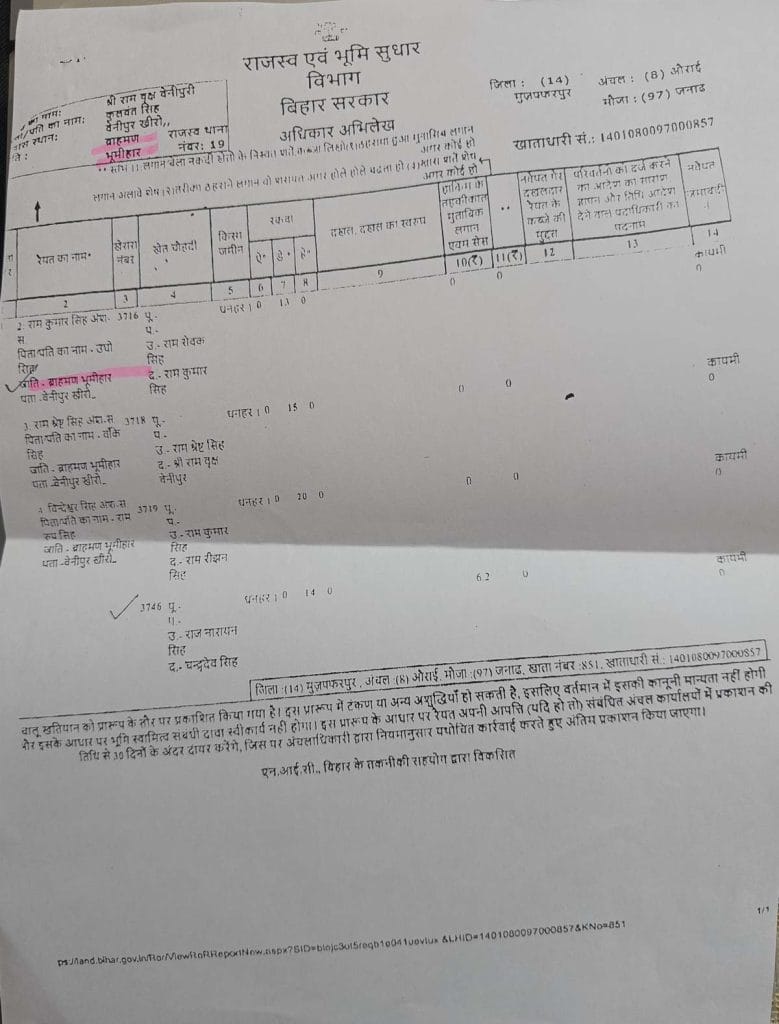

Beyond social prestige, property was another worry. In a state where more than 60 per cent of crime is linked to land and property disputes, the software used for CM Nitish Kumar’s ambitious land records digitisation program uses only the ‘Bhumihar’ tag. It’s caused anxieties over potential title disputes.

The Patna High Court took up the matter on an urgent basis. Justice Mohit Kumar Shah, in an order in November 2023, asked Kumar’s counsel to approach the State Commission of Upper Castes and the respondent authorities.

If the central government too uses the word ‘Bhumihar’ for our caste in the census then we will have no option. So before that, we reached out to them

-Dhirendra Kumar, journalist

Kumar said he wrote repeatedly to the concerned state departments, but they did not respond. It might have faded away, but in April 2025, the Modi government announced the caste enumeration exercise for the 2027 Census.

This galvanised Kumar again. This time, he wrote to the Home Ministry.

“If the central government too uses the word ‘Bhumihar’ for our caste in the census then we will have no option. So before that, we reached out to them,” said Kumar.

The Home Ministry took cognisance of his concern and forwarded it to the state government for a response.

This was around the time that the Nitish Kumar government had revived the dormant Savarna Ayog. The Bihar government sent the matter to the commission seeking recommendations last year.

Almost immediately, the Ayog’s office was flooded with applications from Bhumihars across the state.

“For over a month the people sent their land records which mentioned Bhumihar Brahmin as their caste. Our office was full of petitions, letters, and old documents,” said Mahachandra Prasad Singh, president of the Savarna Ayog and a member of the Bhimihar community himself. “There were hundreds of documents.” A corner of his office is piled with these submissions, including district circle records and land titles on Rs 100 stamp paper.

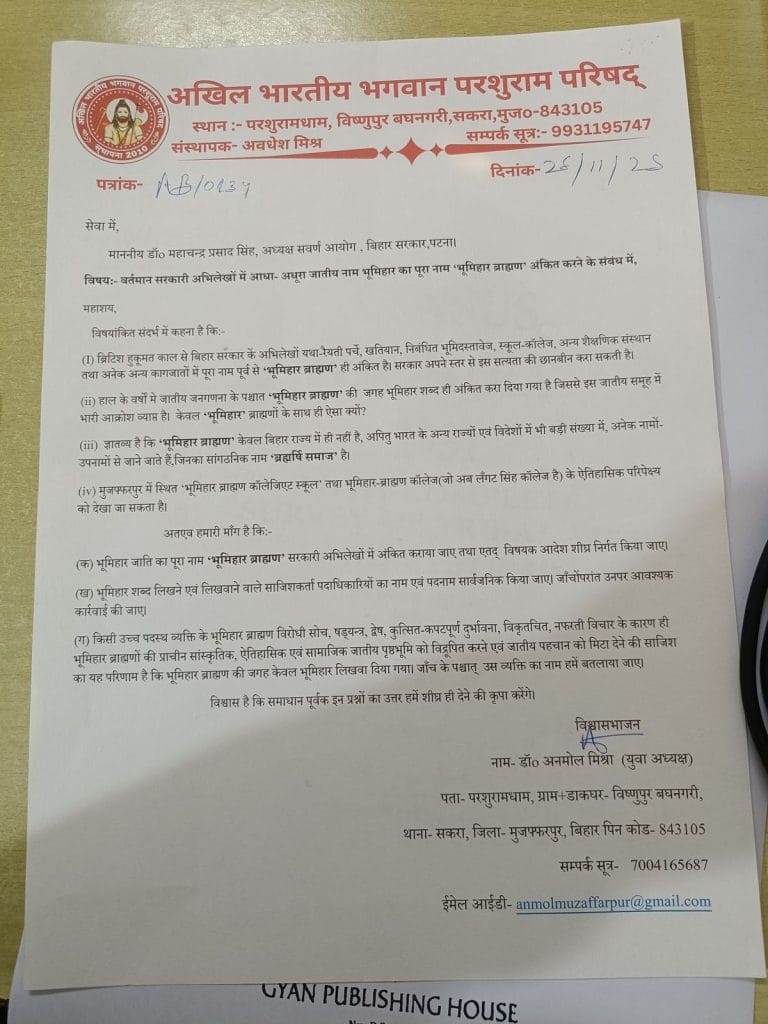

When the Ayog president went to Muzaffarpur in November, a delegation of the Akhil Bhartiya Bhagwan Parshuram Parishad, a Bhumihar association, submitted a formal memorandum, titled, ‘Regarding the inclusion of the full name Bhumihar Brahmin instead of the incomplete caste name Bhumihar in current government records.’

Even Bhumihar stalwarts of Hindi literature have been invoked. In December 2025, someone sent land records of the famous Hindi writer and editor Rambriksha Benipuri to the Ayog. At his office in Patna’s Vidhayak Colony, Singh pointed to the column where Benipuri’s caste was written as ‘Bhumihar Brahmin’.

“The earlier land records are solid proof,” Singh said, adding that the Ayog has sent its view to the government and is awaiting a response.

However, not all Bhumihars are hankering for the Brahmin label.

Demand for OBC category

In Bihar’s complex social landscape, the Bhumihar community is navigating a dual identity crisis. Their upward mobility quest isn’t uniform. While some in the community want to assert their Brahmin roots, others are pushing for OBC status. They are citing data that shows the image of a landed elite is at odds with their economic struggles.

Bhumihars are still widely associated in Bihar with zamindari power, despite the fragmentation of holdings. One oft-cited, though unverified, estimate comes from the Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF), which has claimed that Bhumihars control 39 per cent of Bihar’s land. However, there is no official caste-wise landownership data in the public domain. The Bandyopadhyay Commission on land reforms submitted a report in 2008, but it was never made public by the Nitish Kumar government.

What truly challenged perceptions was the 2023 caste survey report, which revealed that 27.58 per cent of Bhumihars come under the ‘poor’ category, which means they earn less than Rs 6,000 per month. Only extremely backward classes, SCs, and STs are more economically deprived.

The report findings propelled Patna-based Bhumihar activist Alok Kumar Singh to organise a meeting in January 2024 and announce the Bhumihar OBC Sangharsh Morcha, which campaigns for the inclusion of Bhumihars in the OBC category. Its members contend that being counted as OBCs will ensure job quotas and political capital. Their social media posts feature the hashtag ‘BhumiharWantsOBCStatus’.

“It is true that Bhumihars were once the dominant caste but that is not true in the current world. We demanded OBC status on the basis of government data,” said Alok Kumar, president of the Bhumihar OBC Sangharsh Morcha.

In the meetings, people say that if we move from the Brahmin list to the OBC list, it will affect our social prestige

-Alok Kumar, president of the Bhumihar OBC Sangharsh Morcha

Over the past two years, he has been working to unite the Bhumihar community in Bihar and beyond. He has held dozens of meetings in all the districts with a sizeable Bhumihar population, including Begusarai, Gaya, Arwal, Jehanabad, Patna, Bhagalpur, Muzaffarpur, and Lakhisarai.

But his organisation’s mandate isn’t easy to stomach. He is, in essence, demanding a social downgrade.

“In the meetings, people say that if we move from the Brahmin list to the OBC list, it will affect our social prestige,” he said.

Alok Kumar patiently informs the doubters that in Maharashtra many Brahmin communities and priestly groups are listed in the OBC list. In the Tuljapur area of Marathwada, Maratha and Brahmin families have been getting OBC certificates based on documents available in Nizam records.

The image of the Bhumihar as a wealthy landlord has harmed the community, according to him. He notes that while the community still clings to raub (clout) and the title of Zamindar, those days are long gone. With each generation, land is fragmented through batwara (partition among brothers), and agriculture is no longer as profitable.

“There was a time when our caste was at the forefront, but now they need social, economic, and political security,” he said.

Yet, for many Bhumihars, ancestral pride is more important than quota.

Sammelans, sabhas, and social media

From Begusarai to Uttar Pradesh to Delhi-NCR, Bhumihar groups are using sammelans (gatherings), sanghathan (organisations), and social media as modern weapons to assert their relevance.

On 18 January, the Bhumihar Brahmin Parivar Trust celebrated Makar Sakranti with a massive ‘Sneh Milan Samaroh’ in Ghaziabad, with over 700 people attending, including MPs and former ministers.

Just a few days prior to this, another organisation, the Brahmrishi Sammelan, organised a similar gathering in Delhi’s Dwarka, where Savarna Ayog president Mahachandra Prasad Singh was the chief guest.

“Our social unity will become the greatest strength of the future,” said Ratan Sharma, chairman of Bhumihar Brahmin Parivar Trust.

Back in Begusarai’s Bihat, the hot topic of conversation among a group of 20-something men was a grand 10-day mahabhoj (feast) organised to commemorate the death anniversary of the Bhumihar industrialist Ram Kripal Singh. It was reportedly the largest feast in India and fed a million people.

Among these young men, the sentiment was fiercely elitist. Satyam Singh Vikas, a Delhi University graduate who returned home to start a business, scoffed at the idea of Bhumihars being “backward”.

“I can’t work under anyone’s leadership,” Vikas said, scrolling through his iPhone. “Bhumihar kisi ke andar dabkar nahi reh sakta” (A Bhumihar cannot live suppressed).

This bravado is baked into even Bhojpuri songs, with popular titles such as Bhumihar ke talwar (The swords of the Bhumihars), Marad Bhumihar (The manly Bhumihar), Bhumihar ke Dhamaka (The Bhumihar explosion), and Prakhand ho ya zila, Bhumihar se hila (Be it a subdivision or a district, it trembles before the Bhumihar).

I can’t work under anyone’s leadership. Bhumihar kisi ke andar dabkar nahi reh sakta (A Bhumihar cannot live suppressed)

-Satyam Singh Vikas, Bihat resident

Facebook and Instagram have become the latest vehicles for this swagger. Kanhaiya Singh, a mechanical engineer, posted a reel on Instagram in which he is driving his white Thar. “Bhumihar means royalty. Everyone can’t afford it,” reads the caption. Another post flaunting the Bhumihar caste reads: Baate pe goli ke bochhar ho jaayi, Boli koi bhabhan se to maar ho jaayi (If you argue, you’ll be met with a hail of bullets. If anyone speaks rudely to a Brahmin, a fight will break out).

The first Bhumihar mobilisation

It is not the first time the Bhumihar identity pendulum is swinging ahead of a census. A century ago, it was the Bhumihar aspiration that the British enumerators encountered. Now, it is the Bhumihar desperation that India’s caste census surveyors will grapple with.

Along with Kayasthas, Bhumihars were among the castes that spearheaded pride politics and caste mobilisation in the late 19th century.

“Bhumihars systematically initiated a campaign using the state apparatus, which at the time was the census,” said Aniket Nandan, professor of sociology and social anthropology at Indian Institute of Science and Education Research (IISER), Bhopal. “Their story is grey, ambiguous, and complex.”

Nandan described the colonial census as a site of political contestation that saw a wave of petitions from communities trying to negotiate their Varna rank upwards. Caste associations began producing genealogies, histories, and mythologies to demonstrate Kshatriya or Brahmin status.

The Bhumihar campaign produced two key organisations set up by zamindars and elites. The Pradhan Bhumihar Brahman Sabha was established in 1889, followed by the Bhumihar Brahman Mahasabha in 1896.

Swamiji gave dignity to the Bhumihar community. If he hadn’t guided members of our community to become purohits, it would have become even more difficult for us to prove ourselves as Brahmins

-Pinesh Kumar Singh, caretaker of Sitaram ashram

Many district-level bodies were also formed, Teltumbde wrote in The Caste Con Census, with these groups orchestrating a flurry of petitions “backed by scriptural citations and ancestral lore.” Colonial enumeration, he added, transformed caste from a local, relational structure into a politicised and standardised identity.

A turning point for the nascent movement was the arrival of the ascetic and peasant leader Swami Sahajanand Saraswati into the Bhumihar Brahman Mahasabha. It was he who encouraged Bhumihars to venture into traditionally Brahmin domains.

“He was of the opinion that the Bhumihars should play the role of a priest (purohit) to perform family rituals, such as shraddha (homage to departed elders) and vivah (marriage) as the Brahmans did,” Nandan wrote in a paper published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Historical Sociology.

However, this vision created internal friction. In his autobiography, Mera Jivan Sangharsh, Sahajanand Saraswati wrote that the Mahasabha was divided over the issue of purohiti, with opposition coming from rich, landed community leaders such as Sir Ganesh Dutt.

Despite the internal rift, Saraswati’s call for priestly work cemented his status as a celebrated figure. Today, his image as a Dandi Sanyasi of the Dashnami order is a staple at Bhumihar gatherings and on posters.

The Sitaram Ashram, established by Saraswati in Bihta, about 30 km from Patna, was once a buzzing venue for Bhumihar and Kisan Sabhas, although now it looks deserted.

“Swamiji gave dignity to the Bhumihar community,” said Pinesh Kumar Singh, the caretaker of the ashram, while turning the pages of Saraswati’s autobiography. “If he hadn’t guided members of our community to become purohits, it would have become even more difficult for us to prove ourselves as Brahmins.”

Mandal and militias

If the pre-independence Bhumihar movement spoke the language of priesthood, it would later become increasingly associated with land, power, and, eventually, force.

In the decades after Independence, Bhumihars had a storied grip on the Bihar Congress establishment, with a cadre of powerful leaders such as Shri Krishna Singh, Mahesh Prasad Sinha, Krishnakant Singh, and LP Shahi.

“After the 1930s Bhumihars went closer to the Congress and occupied a powerful position in the party. It was the time they had immense land holdings,” said Nandan.

But political shifts of the 1980s and 1990s changed everything, especially after the Mandal Commission threw up a new power elite.

“The rise of social justice movement in Bihar hit them badly,” said Nandan.

Along with the weakening of the old order, another rupture came in the form of Naxalism in central Bihar. Left-wing armed groups mobilised landless labourers, while upper caste landlords answered with private armies. It started with the Rajput-led Kuer Sena in 1979, but the Bhumihar militias were the most feared, from Sunlight Sena to Brahmrishi Sena to the Savarna Liberation Front (SLF).

After the 1930s Bhumihars went closer to the Congress and occupied a powerful position in the party. It was the time they had immense land holdings… The rise of social justice movement in Bihar hit them badly

-Aniket Nandan, professor of sociology

The conflict turned bloody in 1992 when the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) attacked Barra village in Gaya, killing 35 Bhumihars. In the wake of the massacre, SLF chief Ramadhar Singh issued a chilling warning: “Mera itihas mazdooron ki chita pe likha jayega” (My history will be written on the pyres of labourers).

But the most notorious Bhumihar militia of all was the Ranvir Sena, formed in 1994 and led by Brahmeshwar Mukhiya.

At its peak, the Sena had access to an estimated 17,000 licensed weapons held by the community. Their ideology, as revealed in their pamphlets, combined anti-communism and mythology.

“The communists have been defeated in Russia and Eastern Europe; now they must be uprooted in India also,” read one Ranvir pamphlet. In another, Mukhiya invoked the warrior-sage Parshuram: “I did what Parshuram did. Violent methods are necessary… otherwise injustices will prevail.”

Over a decade after Mukhiya was gunned down by unidentified gunmen in 2012—an event that sparked state-wide protests—he is still an icon for many Bhumihars.

“During Lalu’s era, the Bhumihar community was the only one that did not bow down. Mukhiyaji taught us to live with self-respect,” said Pinesh Kumar Singh at the Sahajanand Saraswati Ashram. “Hamare samaj ke liye devtulya the” (He was like a god for us).

Pinesh Kumar, however, lamented that the community’s prestige was declining and that the trajectory was changing from Zameendari to Rangdaari (gangsterism).

The transition from the ‘ruling class’ to a ‘fighting class’ is still central to the Bhumihar psyche.

“Their (Bhumihars) clout has been waning lately with the rising awareness among the hitherto oppressed classes, they have guarded their hierarchical and social status more vehemently than any other upper caste in Bihar,” wrote Mrityunjay Sharma in his book Broken Promises : Caste, Crime and Politics in Bihar. “The caste army was one such manifestation and seemed for them to be the last hope of guarding their privileges and making a political comeback.”

As they soaked in the winter sun in Bihat, the group of friends spoke passionately of glory days that had passed well before they were born.

“We are the ones who stood against Lalu Yadav’s regime in the 1990s,” Vikas announced.

Recalling the peak of the 1990s, his friend Surya Singh, who has worked with Jitan Ram Manjhi’s Hindustan Awam Morcha, pointed out that many Bhumihars adopted neutral surnames like Raj or Anand because of the “fear that gripped the savarnas at that time.” However, he added that the Bhumihars’ political footprint is still disproportionate to their size.

“We still dominate Bihar politics. Hum ginti mein kam hain iska matlab ye nahi hai ki hum kamzor hain” (Just because we are few in number doesn’t mean we are weak), he said.

Chest-thumping slogans are common in the community. One goes: Nadi nala sarkar ke, baaki sab Bhumihar ke (Rivers and streams belong to the government, the rest belongs to the Bhumihars). Another, which became popular after Nitish Kumar’s 2005 victory, still does the rounds: Kurmi ko raj, Bhumihar ko taaj (Kurmis get the kingdom, Bhumihars get the crown).

In the 2025 Bihar elections, the NDA fielded 32 Bhumihar candidates. Two are now in Nitish Kumar’s cabinet: his close aide and water resources minister Vijay Kumar Chaudhary, and Deputy Chief Minister Vijay Kumar Sinha.

Also Read: Chandigarh was India’s envy. Now it’s losing the edge, becoming just another Indian city

Warriors, sages, zamindars

For all the petitions and surveys, the Bhumihar story has never had a single clear origin tale. There are multiple storylines of land, ritual, myth, politics.

In Mokama, on the busy Patna-Kolkata rail route, Bhumihars have a temple dedicated to Parshuram, the warrior-sage who holds an axe. During evening prayers, a priest calls out Parshuram bhagwan ki jai.

“Parshuram is a source of pride for us. We align our lineage with him,” said devotee and regular visitor Rakesh Singh, standing at the temple premises.

The Bhumihar-Brahmin identity often rests on a particular self-image: not priests but Brahmins who ruled and farmed. Singh pointed the Maharaja of Tekari, Hathua Raj, and Bettiah Raj, revered for having helped consolidate the community’s claim to ruler status.

Scholars have sometimes divided Brahmins into two broad categories: yachak (who perform priestly duties and accept alms) and ayachak (those who did not).

“Bhumihars are a prominent ayachak brahmin community of East India. Ayachak brahmins gave up priestly duties and took up agriculture for subsistence and bore arms to protect the motherland,” wrote Anurag Sharma, author of Brahmins Who refused To Beg: Brief History of Bhumihars, Ayachak Brahmins of East India.

But there are also other takes on the Brahmin antecedents of the Bhumihars. The British-era historian and Sanskrit linguist Haraprasad Shastri has argued that Brahmin groups who had converted to Buddhism later returned to Hindu society with a lowered ritual rank. At the same time, they also took over lands and shrines attached to abandoned monasteries. Shastri connected the name Bhumihar to bhumi-haraka, or “land-usurper”.

Historian William Dalrymple also noted the Buddhist connection of Bhumihars in his book Age of Kali: Indian Travels and Encounters.

It is land, though, that is the community’s most enduring marker. DM Diwakar, economist and former director of the AN Sinha Institute of Social Sciences, argued that this could be traced to colonial property regimes. The British, he said, turned land into a commodity when the zamindari system was formally established through the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793.

“Those who were close to the British became landowners during that period. Since the Bhumihar community was concentrated in parts of North India, they acquired land ownership rights there and became owners of large tracts,” added Diwakar.

The community’s landlord legacy has been explored through various literary and cinematic lenses. The 2021 short film Bhumiyar by Prashant Rai depicts the a community that makes land ownership a part of their identity despite not actually having much land to their name. In literature, the novel Balwant Bhumihar by Bhuvneshwar Mishra, published in 1902, was so unrelenting in its depiction of landlord atrocities that almost all copies were immersed in the Ganges in Varanasi shortly after publication; it was republished only recently.

The Bhumihar identity, however, is not monolithic; it also adapts to the geography of Bihar. In the Mithila region, for instance, they often use the surname Mishra and maintain a roti-beti (meal-sharing and marriage) relationship with traditional Brahmins.

“This is not common,” said Shubhash Mishra, a Muzaffarpur priest. “In the rest of the state, Bhumihars only marry within their own caste.” He did, though, add the traditionalist rider that “actual” Brahmins were only those who do priestly work.

Surnames also capture regional variations among Bhumihars. In Gaya, Jehanabad, and the suburbs of Patna, Bhumihars use names such as Chaudhary, Upadhayay, and Singh. In Munger, Begusarai, and Lakhisarai, Singh is more common. In the districts near Patna, the community is perceived as less ‘muscular’ whereas in Begusarai, Munger, and Lakhisarai—where they speak the Magahi language—Bhumihars are said to be more assertive.

On caste pride, there have long been internal contradictions as well. The ‘Rashtrakavi’ Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, a literary icon for the community, rejected casteism and called it an accident of birth in a 1961 letter.

“The best way to reform the infamous state of Bihar is for people to forget castes and unite in respecting the meritorious,” he wrote.

Yet, for Vikas in Bihat, Bhumihars are the ruling class, and no other caste is as capable as his.

“Bhumihars have brains like Chanakya and power like Parshuram,” he said.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

A Baseless and Misleading Narrative on Bhumihar Brahmins

The article published is an attempts to construct a narrative of “identity confusion” around the Bhumihar Brahmin community. Unfortunately, this piece is less an exercise in serious historical inquiry and more a manufactured perception, relying on selective colonial records, sociological speculation, and present-day political vocabulary to question an identity that is historically, genealogically, and culturally well established.

Colonial Classification ≠ Civilisational Reality

The article repeatedly leans on British-era caste classifications, suggesting that Bhumihars were treated as Vaishyas in Bihar and “later lobbied” to gain Brahmin status. This argument is deeply flawed.

Colonial censuses were administrative tools, not arbiters of dharmic or genealogical truth. British ethnographers frequently misclassified Indian communities due to:

Regional variation in titles and occupations

Their own rigid European notions of caste

Reliance on local informants with political motives

To imply that Brahminhood is something that can be granted by colonial rulers is itself intellectually absurd. Brahmin identity predates British rule by millennia and is determined by gotra, pravara, shrauta-smarta practices, family lineage, and ritual status—not by census tables.

Kanyakubja Vanshavalis Directly Contradict the Article

The article’s thesis collapses when confronted with genealogical literature.

All major Kanyakubja Brahmin Vanshavalis clearly record:

The Battle of Madarpur

The eastward migration of Kanyakubja Brahmins into Magadh, Bhojpur, Ballia, Ghazipur, Allahabad, and adjoining regions

The settlement of these Brahmins as landholding, tax-paying agriculturists without abandoning their Brahmin ritual status

These are not isolated references. Every major Kanyakubja Vanshavali acknowledges this tradition. If Bhumihars were not Brahmins, their systematic and consistent inclusion in Brahmin genealogical texts becomes inexplicable.

Zamindari Records Explicitly Mention ‘Brahmin’

The article conveniently ignores land, revenue, and estate records.

Bhumihar Zamindaris of Allahabad, Ballia, Ghazipur, Shahabad, Saran, Champaran, and Tirhut consistently record the holders as Brahmins

The Hathwa Raj, with a lineage traceable to the 7th century, is a well-documented Brahmin house

These records predate late colonial lobbying narratives and stand independent of British caste politics

Revenue documents are among the most conservative and precise historical records. They do not invent caste identities lightly.

Magadh ‘Babhan’ Identity Is Ancient, Not Invented

In Bihar—especially Magadh—the term Babhan has been used for Brahmins for centuries. To suggest that Magadh’s Babhans “became Brahmins later” is to erase:

Regional linguistic usage

Buddhist and post-Buddhist Brahmin settlements

References in local traditions, mathas, and temple networks

Bhumihars are not a recently assembled pressure group; they are among the oldest settled Brahmin communities of eastern India.

Misleading Obsession with Titles like ‘Singh’

The article further attempts to confuse readers by highlighting the use of the title Singh.

This reflects poor understanding of Indian social history:

Singh is not exclusive to any one caste

Numerous Brahmin communities—especially landholding and martial Brahmins—have historically used it

Brahmins do not have a single common title, because:

There are over 2,000 Brahmin sub-sections

More than 500 recognised Brahmin sub-castes across India

Using titles to question Brahminhood is academically unserious.

Identity Is Not Decided by Media Narratives

The most problematic aspect of the article is its underlying assumption that Bhumihar identity is up for external arbitration.

In reality, Brahmin status is determined by:

Family trees (Vanshavali)

Gotra and pravara

Ritual practices

Temple and math affiliations

Land and revenue records

Continuous social recognition over centuries

It is not decided by journalists, colonial officers, or contemporary political categories like OBC/forward/oppressed.

A Political Lens Masquerading as History

By framing Bhumihars as “confused” between Brahmin, OBC, zamindar, or oppressed, the article:

Imposes modern political binaries on pre-modern identities

Delegitimises a community’s historical self-understanding

Encourages social fragmentation rather than scholarly clarity

This is not neutral reporting; it is narrative engineering.

Conclusion

The attempt to portray Bhumihar Brahmins as a community that “lobbied its way into Brahminhood” is baseless, historically inaccurate, and intellectually dishonest.

Bhumihars have been Brahmins by lineage, scripture, genealogy, and social recognition long before colonial rule—and they remain so irrespective of contemporary political fashions.

History should be studied with sources, not with agendas.

Only economic criteria should be used for deciding GEN/OBC/SC/ST.

Whether they are culturally Brahmin or not, should be decided on, whether they practice brahmin rituals or not.

End of story.

Why was land reforms not implemented in bihar…. Its because land in bihar belonged to bhumihars… Who supported pandit nehru… While in up, Rajasthan, haryana, Punjab…. It belonged to rajputs, jats, and gujars… So it was implemented their…. So pandit Nehru in a way showed that he is a pandit first then a prime minister