New Delhi: When a Varanasi district court in July 2023 directed the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to conduct a scientific survey inside the Gyanvapi mosque complex — a contentious religious site in Uttar Pradesh long at the centre of competing claims — the Narendra Modi government turned to a man few outside archaeological circles were familiar with: Alok Tripathi.

Then, there is something called timing. Tripathi was there at the right place, right time. His moment had come.

For nearly four decades, 60-year-old Tripathi had worked in relative obscurity, diving into the Arabian Sea to study the holy Krishna city Dwarka’s submerged ruins, deciphering inscriptions in temple towns, and navigating the slow, methodical routines of a discipline rarely visible to the public. Dwarka was a long, lonely quest that late archaeologist SR Rao had passed on. But Gyanvapi thrust him into the national spotlight. Suddenly, his work was no longer confined to excavation trenches, deep sea dives and institutional reports. Now, in his second stint at the 165-year-old ASI, Tripathi has become the face of the Modi government’s most sensitive assignments since his ghar wapsi to the institute after a decade.

What architect Bimal Patel is to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s architectural ambition — reshaping the Kashi corridor, Delhi’s Central Vista, and designing the new Parliament building — Tripathi has become its go-to archaeologist no 1.

His expertise in underwater archaeology, long seen as a fringe specialisation within the ASI, gained new institutional value as the government turned its attention to Dwarka. In another era, Tripathi might have remained a footnote in ASI files. But in Modi’s India, he possessed a rare currency: niche experience.

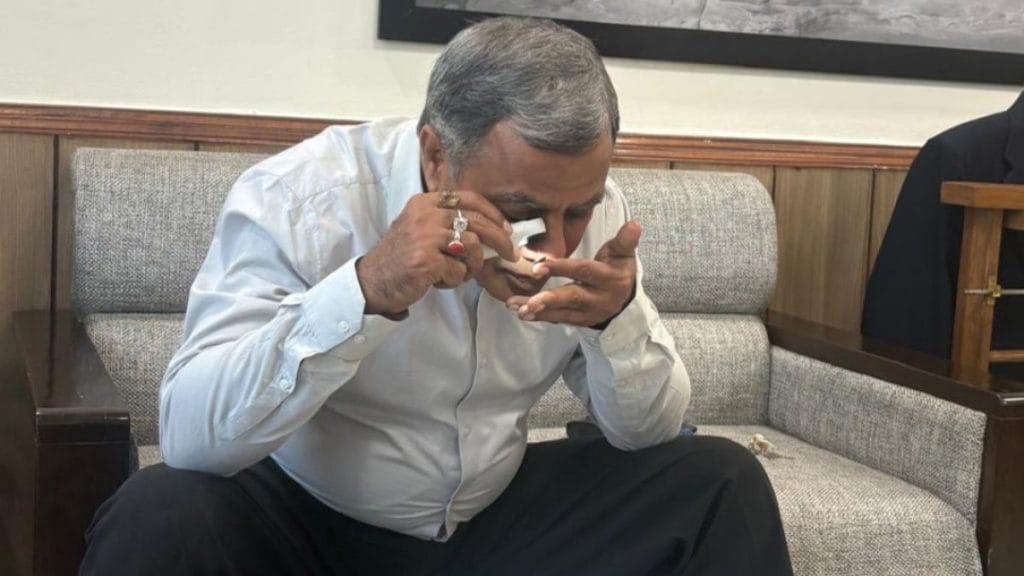

Inside his office at ASI headquarters in Delhi’s Dharohar Bhawan, there is little outward sign of his new-found influence in archaeological and political circles. With gemstones on his fingers and several sacred threads on his wrist, Tripathi speaks with the calm detachment of a career official. In person, he is measured, almost austere. But his social media suggests he is acutely aware of his critics.

There is no grand ideological flourish in his words, only a steady assertion of professional competence. He truly belongs to the era of faceless, self-deprecating archaeologists. His politics is not overt, his utterances aren’t over-the-top. His underwater expeditions were precisely what was needed for the Modi government’s renewed emphasis on Dwarka. And yet, many know of him as the archaeologist who has already got four post-retirement extensions.

“My work is based on contextual interpretation. This is the approach I followed since my early days in archaeology. This is my capacity and ability,” Tripathi added, leaning back into a grey sofa.

Tripathi’s tryst with history

Inside ASI headquarters back in 2023, the Gyanvapi court order triggered urgency. Phones rang, meetings were convened, and the leadership faced a critical question: “Who would lead the most politically sensitive archaeological exercise of the decade?”

Tripathi emerged as the choice but he was not the obvious one.

He had joined the ASI in 1987 after developing an early fascination with archaeology while studying rock shelters and inscriptions in Gwalior. Over the decades, he built expertise in both terrestrial and underwater archaeology, a rare specialisation within the organisation.

“He was not the consensus choice,” said a senior ASI official, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “His core expertise is underwater archaeology. Many felt others were better suited. But somehow, he ensured the task came to him.”

Murmurs were rife when Tripathi was selected for Gyanvapi: “Koi bada jugaad lagaya hai Tripathi ne (Tripathi must have pulled some strings).” But he rejects suggestions that anything beyond protocol influenced the decision.

“At that time, I was among the senior-most officers at ASI after the Director General. That’s why I was entrusted with the task,” he said on the survey that altered his career trajectory.

Once appointed, he maintained strict silence in public, citing the matter as sub judice. He is careful with his words, particularly when it comes to allegations of bias. “At the site, we took all stakeholders together,” he added. “Nothing was done through a biased lens, everything was strictly professional.”

His role nevertheless transformed his position within the institution and beyond it; he was now the modern-day Indiana Jones of the ASI.

“In a country where archaeology has become a proxy battlefield for history, faith and identity, Tripathi’s role has transformed from that of a career official to a consequential actor,” said a senior archaeologist familiar with ASI’s functioning.

When he cemented his position

If Gyanvapi brought Tripathi into public view, Bhojshala cemented his importance within the government.

The Bhojshala complex in Madhya Pradesh’s Dhar — claimed by Hindus as a temple dedicated to goddess Vagdevi and by Muslims as a mosque — had become the subject of renewed legal scrutiny. Tripathi was once again assigned to lead the survey.

Before entering the site, Tripathi wrote to authorities in Indore requesting safe and uninterrupted access to the site. His team worked methodically for months. The final report exceeded 2,000 pages and documented artefacts recovered during the excavation, including an idol identified as Vagdevi.

“Whatever be the project assigned to me, the results are based on material evidence,” he said. “The same happened in the Bhojshala case.”

The findings didn’t remain confined to courtrooms and files.

Last year, when Modi visited Dhar he made a public reference to Vagdevi at a gathering. “I bow at the feet of the Goddess of Knowledge and Maa Vagdevi of Dhar Bhojshala,” he said.

Within institutional and government circles, Tripathi’s stature rose steadily. Last year, he was instrumental in bringing back Buddha’s Piprawaha relics, his last key assignment from the government.

He was also inducted into the organising committee of the Gyan Bharatam conference, a flagship cultural initiative focused on India’s civilisational heritage. There, he chaired discussions on deciphering ancient scripts, including the still-undeciphered Indus script.

“The day the Indus script is deciphered, India’s history will go back at least by 3,000 years,” he said.

His remark captured both the ambition of the conference and the larger ideological project it represented — one in which archaeology was no longer just about the past, but about reshaping how that past is imagined and claimed in the present.

Tripathi deliberately says “since” Independence instead of “post”, suggesting that India’s archaeological narrative is part of a larger ongoing story rather than a new beginning.

Rock caves to underwater archaeology

Tripathi’s story goes all the way back to fossils, literally, from his childhood. When he was in class 4, he was first introduced to archaeology by his teacher Jagdish Ji Dewra with a peek into fossil photographs.

“It was the starting point where interest grew but in my college days at Science College, Gwalior, I discovered rock paintings and shelters which was the most fascinating thing for me,” Tripathi reminisced about the old days with enthusiasm.

Later, his encounter with archaeologist VS Wakankar, who discovered the Bhimbetka caves, proved to be a turning point.

“Wakankar was my first guru,” Tripathi said. With that push, he cracked the SSC exam and joined the ASI in 1987; his first posting was at Khajuraho.

He spent several hours seeing the sculptures of Khajuraho, reading inscriptions of the Chandela dynasty.

“One day I saw two Royal figures and a question clicked to my mind: who are they? Based on inscriptions I found the Chandela brothers Jay and Vijaya,” said Tripathi. He didn’t stop there and traced all the genealogy of Chandela Kingdom.

His findings were a major attraction in 1988 at a Shantiniketan conference where he presented his paper on Chandela’s figures. The house was divided but Wakankar’s words echoed in Tripathi’s mind. “Tumko jo sahi lage vahi kaho (Say what you think is right).” He remembers his words even now.

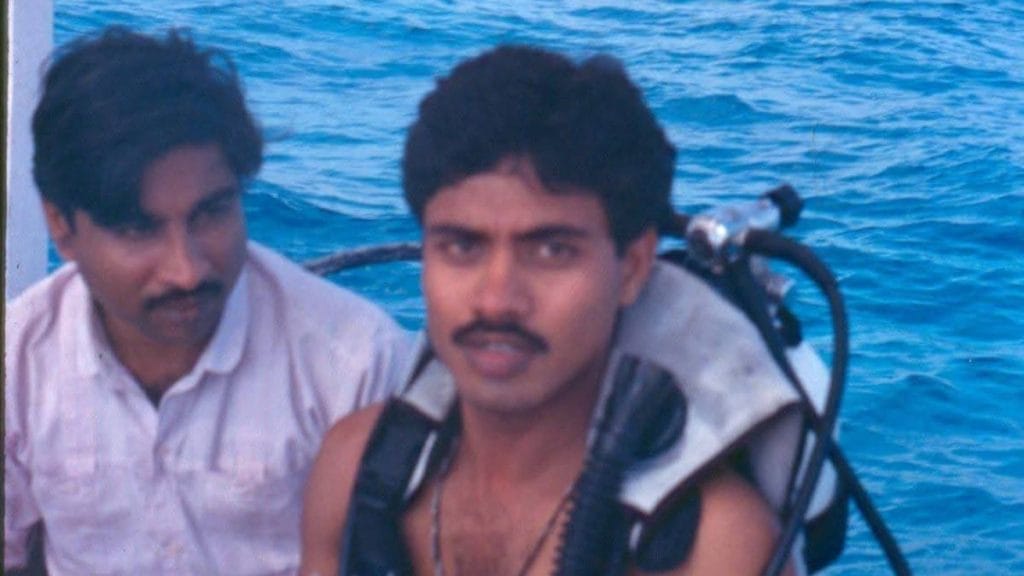

The same year, Tripathi got selected in the Underwater Archaeology Wing of the ASI. He had experience of working with the Navy as a NCC cadet. He learned diving in the 1990s under the legendary underwater archaeologist SR Rao, the pioneer who first hinted at Dwarka’s submerged remains, and trained at the National Institute of Oceanography (NIO) in Goa. He was sent to France on a cultural exchange program where he worked in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Ocean.

“Diving in India was so rare that time and equipment were limited,” he said, adding that the underwater wing gained shape in 2001 and was a turning point. Tripathi said the Indian Navy supported them and with their help the ASI explored areas of Lakshadweep, Mahabalipuram and Dwarka.

Finding the past under water

When the Modi government looked away from temples-mosques and turned seaward towards Dwarka in 2022, they looked to Tripathi. He is the ASI’s lone underwater archaeologist, with nearly 35 years of experience. In 2009, he moved to academia, teaching archaeology at Assam University before returning to ASI over a decade later.

When he returned to the ASI in 2021, Tripathi made it his mission to revive the organisation’s long-neglected Underwater Archaeology Wing (UAW), which had been dormant for nearly a decade. The idea found little enthusiasm at first. Files moved slowly, scepticism lingered.

By February 2025, his team had resumed explorations off the coast of Dwarka.

The project acquired more significance after Modi personally dived near Dwarka in 2024, describing the experience as “divine.”

Under UAW 2.0, Tripathi’s team expanded its canvas, surveying Dwarka, Mahabalipuram and Manasbal in Kashmir.

“The submerged heritage is present across the country,” Tripathi said. “And interestingly, most of it remains undisturbed.”

Once limited to hazardous dives and rudimentary equipment, underwater archaeology now relies on remotely operated vehicles, high-resolution sonar mapping and deep-sea imaging. Landmark discoveries like the Bronze Age Uluburun shipwreck off Turkey to the Black Sea Maritime Archaeology Project in Bulgaria have demonstrated how submerged sites can offer some of the most intact historical records, reinforcing the importance of underwater archaeology.

Yet, not everyone at ASI was convinced.

Some archaeologists privately questioned Tripathi’s evolving position on Dwarka. The scepticism stemmed from his own words nearly two decades earlier when Tripathi had publicly played down claims of a temple beneath the sea.

“We have to find out what they are. They are fragments,” he had said in 2007. “I would not like to call them a wall or a temple. They are part of some structure.”

His rise says as much about the changing role of archaeology in India as it does about the man himself.

A geologist associated with NIO for a long time said Tripathi initially refused to discuss the temple remains, but after the Modi government came to power, he began showing interest in it.

“Because this issue is a hot potato,” he said, adding that Tripathi opted for marine archaeology to give him a different identity from his colleagues.

But getting manpower from the ASI was no cakewalk.

“Alok tried very hard. The ASI has always lacked resources. Archaeology isn’t just about diving, they need to demonstrate new work beyond what has been done before,” he said.

It all changed after Dwarka. Tripathi was no longer in the shadows; his conclusions now reverberate in Parliament, courts and on prime-time television. He was now forging a new identity, closer to politicians and farther from his ASI colleagues.

Tripathi’s many extensions

As Tripathi’s stature rose within the ASI and the government’s heritage apparatus, so did scrutiny over the unusual continuity of his tenure.

Tripathi’s second innings at the ASI formally came to an end in April 2024. Since then, his tenure has been extended at least four times. In an organisation where extensions are typically rare and closely scrutinised, the repeated renewals, authorised by the Culture Ministry, did not go unnoticed.

What sharpened the resentment, sources say, was the timing. The past two years have also been the most high-profile phase of his career thanks to Gyanvapi and Bhojshala. The Dwarka exploration was also around the same time. Within ASI headquarters, some officials began whispering about procedural irregularities.

On a few occasions, they claim, the approval for his extension was still pending with the Appointments Committee of the Cabinet (ACC). One source alleged that between 13 April and 9 June 2025, Tripathi continued to use official facilities while formal approval was awaited from the Union culture minister.

He also has a second post – the ADG (Research and Training – Capacity Building) at the ASI.

Sources within the department say that the prescribed age limit for the post is 56, while Tripathi has already crossed 60.

Tripathi, however, dismisses the allegations as misplaced insinuations. He is on deputation from Assam University in Silchar, where he has been a professor since 2009, he said, adding that his retirement age there is 65.

“I have five more years in service. Extensions are part of government procedure. There is nothing unusual about it,” he said.

For some, his continued presence reinforces what they see as Modi’s long standing style of functioning – working with a trusted circle of bureaucrats, a pattern they trace back to his Gujarat chief minister days and now visible in the Prime Minister’s Office and other key institutions.

That hasn’t stopped officials from firing complaints to the ministry against him.

But Tripathi is unbothered. On social media, he does not shout or sermonise. But his posts suggest a man who is aware that his rise has unsettled peers and is unwilling to apologise for it.

“Mujhe samajhna nadano ke bas ka nahi. Phir bhi ye nadani karte hain (It is beyond the power of fools to understand me. Yet they behave foolishly),” reads one of his Facebook posts.

‘Not like a boss’

Whether Tripathi is merely a diligent officer or a bureaucrat who understood the winds shifting early — depends on whom you ask.

Colleagues and his students describe him as methodical, soft-spoken and deeply immersed in his work. Aparajita Sharma, his first PhD student recalled her meeting with Tripathi in 2008 at Delhi’s Indian Archaeological Society (IAS).

“He guides me and pushes me. He is very disciplined and not easily influenced by anyone. He doesn’t behave like a boss,” said Sharma, who is now in-charge of the Underwater Archaeology Wing.

“60 ki umar me bhi unka jajba kayam hai (Even at 60, his spirit remains intact). That gave us strength,” she said, adding that he is ahead of his time. Others describe him as cautious.

“He has a no-nonsense personality and doesn’t exaggerate the findings until he has concrete proof,” one of his juniors at the ASI, who served as a superintendent archaeologist, said.

But museologist Shiv Mishra, who headed several district museums in Bihar was disappointed with Tripathi, when he was director general of National Research Laboratory for Conservation of Cultural Property (NRLC). Mishra recalled a meeting with Tripathi in 2022 in Patna where he asked him for the conservation of objects made from elephant teeth in Bihar.

“NRLC is South-east Asia’s biggest organisation for conservation and Tripathi was heading it. But after repeated requests for conservation, he assured us but didn’t do anything,” said Mishra.

Also Read: Why Modi always hires architect Bimal Patel for pet projects

No Z in archaeology

For Tripathi, archaeology starts with the alphabet ‘a’ and ends with ‘y’.

“There is no z in archaeology so nothing is final. It keeps evolving with time and has a scope always,” he said. Yet in courts and political speeches, his findings are often treated as precisely that.

He never forgot the other lesson given by Wakankar in the 1990s.

“Kisi ke banaye raste par mat chalo, khud ka rasta banao. Yahi maine apni life mein follow kia (“Don’t follow someone else’s path, create your own. This is what I followed in my life),” Tripathi recalled.

His legacy, he says, is ensuring underwater archaeology doesn’t lose relevance again.

“I’m trying to build a strong team of divers and experts who can work on coastal areas so that the UAW can be alive after me,” Tripathi said.

His office reflects the religious tensions inherent in his profession. Inside hangs a painting of Varaha, the mythological Vishnu avatar believed to have lifted the earth from cosmic waters. Outside hangs an image of Humayun’s Tomb. Between those two images from Indian culture lies the tricky terrain he now navigates.

(Edited by Stela Dey)

The facts are visible to the naked eye at Gyanavapi even for the biassed. No need for expert archeologists.