Chhindwara (Madhya Pradesh): A two-room house in Dongar village, Parasia block, is cluttered with medical receipts, hospital papers, and breathing pumps. In a corner lies a small bottle of Coldrif cough syrup. It was prescribed by a doctor and it’s what Afsana Khan trusted with her four-year-old son Usaid’s life. It turned out to be a killer.

“He cried, ammi, take me home, I’m in pain,” she recalled. Hours later, doctors in Nagpur, where he’d been rushed from neighbouring Chhindwara for treatment, declared Usaid dead. She sits on a makeshift iron bed under an asbestos-patched roof, her voice breaking as she remembers that night.

The syrup was meant to treat Usaid’s cold and fever. Instead, it caused vomiting, swelling, and kidney failure. Afsana had promised him she would send him back to school. That promise will remain unfulfilled.

Usaid is one of nearly two dozen children whose lives were cut short by the same syrup over a few weeks—21 in Madhya Pradesh and three in Rajasthan. This small lethal bottle has exposed, yet again, how India’s drug system failed—from a factory floor in Tamil Nadu to rural clinics hundreds of kilometres away. Families describe the same sequence of symptoms: vomiting, swelling, kidney failure, and, in some cases, brain swelling. What began as a local tragedy has become a national reckoning over how poison travelled across the country unchecked in the garb of a cure.

S Ranganathan, owner of Sresan Pharmaceuticals, the Tamil Nadu-based manufacturer, was arrested by a Madhya Pradesh Special Investigation Team in Chennai Thursday; he faces charges under BNS sections for culpable homicide and drug adulteration. A joint regulatory inspection of the company’s facilities exposed a collapse of manufacturing standards, systemic negligence, and potentially criminal malpractice directly linked to the deaths in Chhindwara.

Senior drug officials in Madhya Pradesh have been suspended, and Dr Praveen Soni, a government paediatrician from Parasia who also ran a private clinic and pharmacy, has been arrested—though the Indian Medical Association has defended him. The arrest of the doctor, it said in a statement, “shows an attempt to divert the attention of the people from the faults of regulatory bodies and the concerned pharmaceutical company”.

Since a lot of you Questioned Indian Medical Association for not taking stand regarding Dr Praveen Soni arrest in view of Cough syrup tragedy deaths

Here is the official stand of Indian medical Association @IMAIndiaOrg

This arrest is not justified and we stand with him ?? pic.twitter.com/uzpyOeyW8Y

— Dr.Dhruv Chauhan (@DrDhruvchauhan) October 6, 2025

Multiple states, including Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Kerala have now seized stocks, banned the syrup, and launched awareness drives. The Union Health Ministry has ordered risk-based inspections of drug plants across six states, even as the WHO cautioned that some contaminated batches may have moved through unofficial export channels.

Meanwhile, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) has inspected 19 manufacturing units producing syrups and antibiotics across six states. A sample of Coldrif tested in Chennai was found to be “not of standard quality.” It contained 48 per cent diethylene glycol (DEG), a toxic chemical.

Public anger continues to mount as families grieve with little support beyond Rs 4 lakh in compensation. Opposition leaders have demanded an inquiry, accusing the government of apathy as the deaths climbed.

Dr Kafeel Khan, a paediatrician and public health advocate who first came to national attention after the 2017 Gorakhpur encephalitis tragedy, said the deaths in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan are part of a recurring pattern of regulatory failure.

“If you see the government of India notification from 2023, several fixed dose combinations of cough and cold medicines were banned. But, walk into pharmacies, and the same formulations are available. The drug controller, who issues the production license is the same authority that banned the combination. How are these drugs still coming to market?” he asked. “We’ve had wake up calls before, but the holes in the system remain, the regulations exist, but the water just keeps leaking through.”

Also Read: Small towns are new front in India’s cancer fight. Max & AIIMS doctors in Amroha to Panipat

Tracing the poison

Signs of trouble began in late August, when paediatrician Dr Praveen Soni noticed a surge in children arriving at his private clinic with high fever, swelling, and vomiting. The first clear warning that something was seriously wrong came when a child referred to the Government Medical College Hospital in Nagpur died of kidney failure.

Over the next few days, the Nagpur doctors discerned a pattern: many cases of paediatric kidney failure were coming from the same block in Madhya Pradesh. On 16 September, Nagpur Government Medical College alerted Chhindwara district hospital that multiple patients from Parasia were showing the same symptoms of vomiting, swelling, reduced urination, and kidney failure.

It was just a cold. We thought it would go away in a few days. We bought [the medicine] for Rs 30. That’s the price of Usaid’s life

-Afsana Khan, resident of Dongar village

Between 16 and 22 September, health teams in Parasia began tracing the source of the outbreak. It was a tough task, said Block Medical Officer Dr Ankit Sahlam, since most parents had bypassed government hospitals entirely. Officials tested water samples, checked for food contamination, even looked for rodent-borne infections. They had only a few clues to go on and began a process of elimination.

“If it were waterborne, the entire household would’ve fallen ill. But here, only one child per home was affected,” said Sahlam. The common link soon emerged: a bottle of Coldrif in nearly every home. After his complaint, an FIR was filed against Dr Soni and Sresan Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer.

By then, it was already too late for six children, including Usaid, who’d been prescribed Coldrif by Dr Soni’s assistant at the private clinic. Within a week, his body had began to swell. He stopped eating. Stopped chattering happily. His parents first took him to Chhindwara District Hospital and then, when his condition worsened, to Nagpur—a four-hour journey. Doctors there said both kidneys had failed. He was put on dialysis, but on the tenth day, the machines fell silent.

“It was just a cold,” his mother said. “We thought it would go away in a few days.” She still keeps the empty syrup bottle in a drawer, the cap cracked. “We bought it for Rs 30,“ she said. “That’s the price of Usaid’s life.”

Of the deaths in Madhya Pradesh, 13 were reported from Parasia block alone. Eight bottles of the cough syrup were seized from the homes of the deceased. Other homes where the bottles were found are being closely monitored by government health workers.

So far, over 4,000 blood tests and 1,500 screenings have been conducted across Parasia. Around 700 children with fever are being regularly monitored by ASHA workers.

“Now, the situation is under control,” said Sahlam. “For the last 10 days, we haven’t found any new children with kidney-failure-like symptoms.”

On 24 September, a team from the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and CDSCO arrived in Chhindwara for a field survey to visit households, review prescriptions, and collect samples.

District medical officials clicked photos of the Coldrif bottle and shared these widely on WhatsApp. Health and ASHA workers were mobilised to ensure no contaminated syrup remained in circulation.

“ASHA workers might not understand English, so we wanted them to remember what the bottle looked like,” said Naresh Gonnade, Chief Medical and Health Officer, Chhindwara. “It helped alert local communities and avoid confusion.”

The ‘systemic’ gaps

Drug and health officials said that once suspicions arose, they were instructed to hold back syrups like Coldrif and Nextro DS from sale.

“But unless there’s a report proving the medicine was harmful, it would be difficult to ban it completely. That’s the system—by the time the danger became clear, a lot of syrup was already in circulation,” a senior MP drug department official told ThePrint on condition of anonymity.

The Chief Medical and Health Officer (CMHO) and his team sealed five medical stores and cancelled their licences, recovering 430 bottles of Coldrif. The collector’s advisory came on 27 September, formally prohibiting its sale. Samples were sent to Bhopal on 29 September for analysis, specifically of the ‘SR-13 batch’ of Coldrif, which was found in several cases.

Children went from one private clinic to another, and then to Nagpur. No one informed the health department until it was too late. By the time we connected the dots, days had already been lost

-Dr Ankit Sahlam, Parasia Block Medical Officer

What followed was a slow cascade of communication. On 1 October, the Madhya Pradesh Drug Controller wrote to his counterpart in Tamil Nadu, confirming whether the syrup had been manufactured by Sresan Pharmaceuticals and requesting an immediate probe. Tamil Nadu’s lab detected toxic chemicals by 3 October, and within 24 hours, the state government ordered a complete ban on its production and sale. The Bhopal lab report arrived on 4 October, confirming the same.

“In the end, the delay in action was the gap between private and public care,” said Dr Ankit Sahlam. “Children went from one private clinic to another, and then to Nagpur. No one informed the health department until it was too late. By the time we connected the dots, days had already been lost.”

Even the drug inspector emphasised that tracking patients from other areas was extremely difficult.

“Doctors had been prescribing this syrup for years. Some people had stockpiled it, others had arrangements with doctors. By the time we could act, the damage had already been done. There was no deliberate negligence, only a stretched system trying to respond in real time,” he said.

Defence of a doctor

Dr Praveen Soni, now under arrest, has been practising for nearly 40 years. Patients have been flocking for decades to his clinic from several neighbouring villages such as Dighawani, Chhinda, Barukhi, and Newton Chikhli Kalan, seeking treatment for routine colds, coughs, and fevers.

Ahead of his arrest, Soni remained composed while speaking to the media, answering questions without hesitation.

“I’d examine their children, prescribe medicines, and they would leave,” he said.

For years, Soni had been prescribing the syrup from the same brand, Sresan Pharmaceuticals, without incident.

“This medicine isn’t new; we’ve been prescribing it for years,” he said, adding that it was difficult to believe the recent deaths could be directly linked to the syrup.

It’s wrong to suggest that a primary doctor decides on the formulation. We receive ready-to-use, sealed medicines

-Dr Praveen Soni

Soni maintained that he prescribed dosage based on body weight, and so the question of overdose did not apply. The problem, he suggested, lay not in the prescription, but in how the drug was made.

“It’s wrong to suggest that a primary doctor decides on the formulation. We receive ready-to-use, sealed medicines,” he said.

The IMA has also backed this position, noting in its statement that the “prescribing doctor has no way of knowing whether a medicine is contaminated until adverse outcomes are reported”. It added that regulation must be made “foolproof” to prevent such incidents. Doctors in Chhindwara also staged a protest earlier this week demanding the release of Soni.

The picture, however, was complicated as investigators began tracing how hundreds of bottles of contaminated syrup reached Parasia. Their probe suggests lapses in local distribution and links between Dr Praveen Soni’s family and those supplying the drug.

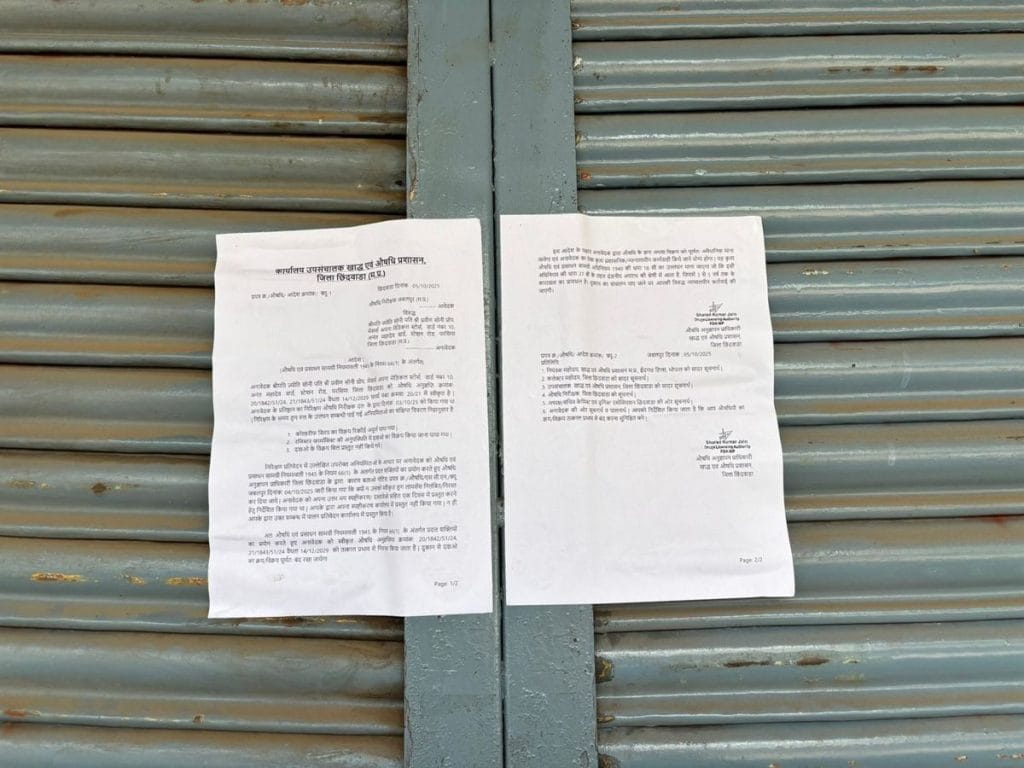

The Madhya Pradesh government has cancelled the licence of Apna Medical Stores in Parasia, run by Soni’s wife, after inspectors found irregularities including incomplete sales records and the absence of a registered pharmacist. Officials are also reportedly investigating whether Soni’s clinic and the local distributor were linked to the 600 bottles of Coldrif dispatched from Jabalpur to Chhindwara, of which about 200 remain untraced. The drug inspectors of both Chhindwara and Jabalpur have been suspended.

From Kanchipuram to Chhindwara

Along the Chennai-Bengaluru Highway in Kanchipuram, a modest blue-walled building stands behind an iron gate. It could pass for a residence were it not for the sign announcing: Sresan Pharmaceutical Manufacturer. It was here that the deadly batch of Coldrif was made.

Neighbours said they barely knew what went on inside.

“We just knew it was a medicine company,” said K Bharathi, who works at a nearby automobile showroom. “About 15 people came by bus or shared auto around 9 am and left by 5.”

Another local businessman, Sakthivel, said the factory appeared normal until 1 October.

“They’d even celebrated Ayudha Pooja. Police and health department officials then started visiting the facility and after a couple of days, the company was shut and we have no clue what went wrong.” According to him, the factory has always employed about 15 people, all from Chennai.

Tamil Nadu’s Health Department has issued a show-cause notice to the company’s owner, S Ranganathan, now under arrest, seeking records of its purchase, manufacturing, and distribution activities. The 73-year-old is a pharmacist by training; his Kancheepuram unit has reportedly held a license since 2011, which is set to be revoked.

Tests by the state Drug Control Department found that Coldrif (Batch SR-13), manufactured in May 2025 and due to expire in April 2027, contained 48.6 per cent diethylene glycol (DEG) — a lethal industrial solvent whose permissible limit is 0.1 per cent. Used in antifreeze, lubricants, and printer ink, it is colourless and odourless but has a sweet taste. Even small doses can cause kidney failure and death.

When we approached [Sresan Pharmaceuticals] for maintenance, they had ignored us. This kind of prolonged neglect can lead to contamination and severe quality lapses, especially in drug manufacturing where hygiene and precision are critical

-engineer at Divya Scientific Engineering Consultancy, which installed its purification unit in 2019

Leading up to this, the Tamil Nadu government’s investigation report points not to isolated errors but to a total breakdown of regulatory compliance, quality control, and ethical oversight.

Overall, 364 violations were found, right from raw material procurement to drug formulation. Of these, 39 were critical and 325 major violations. The plant had no functional Quality Assurance department, released finished products without approval, and kept falsified and overwritten records. Manufacturing areas were unhygienic and poorly ventilated, while the water used for syrups was outsourced, untested, and stored in unsafe conditions.

The inquiry also found that Sresan used non-pharmaceutical grade propylene glycol and failed to test raw materials for toxic contaminants.

“Layout, design and construction of premises is found to lead to unhygienic conditions. No functional AHUs provided, epoxy/coving not found, smooth surfaces for cleaning not provided, plastic pipes are used for transfer of liquid formulations and water used in the mfg of formulations and also GMP drains are not provided. No measures in place to avoid the entry of insects, rats etc,” the report, accessed by ThePrint, said.

Inspectors further found the firm was violating its license by co-manufacturing nutraceuticals and non-drug items alongside medicines without cleaning validation, amplifying the risk of cross-contamination.

ThePrint has also learnt that Sresan’s key purification unit had not undergone recommended monthly maintenance checks for six years.

“The filtration system is crucial for ensuring the purity and safety of pharmaceutical ingredients. This kind of prolonged neglect can lead to contamination and severe quality lapses, especially in drug manufacturing where hygiene and precision are critical,” said an engineer at Divya Scientific Engineering Consultancy, which installed the unit in 2019. “Even when we approached them for maintenance, they had ignored us.”

Following its findings, the Tamil Nadu Drugs Control Department ordered a complete halt to manufacturing, sales, and distribution. It froze the remaining stocks of Coldrif syrup and four other syrups.

However, this wasn’t the first time Sresan Pharmaceuticals has come under the scanner.

Past red flags

Sresan Pharmaceuticals was not an unknown name to regulators. In 2019, a report by the Tamil Nadu Drug Controller had already flagged the company’s cough syrup GM-Cold—a combination of Chlorpheniramine Maleate, Phenylephrine Hydrochloride, and Paracetamol— for incorrect label claims. The report stated that the “sample does not conform to label claim with respect to the content of Phenylephrine Hydrochloride.”

Even a decade ago, there were signs of trouble with Coldrif. Records from the All India Organisation of Chemists and Druggists (AIOCD) show it was among the Fixed Dose Combinations (FDCs) banned in India through General Statutory Rules (GSR) notifications issued on 10 March 2016. Yet, the company was listed as an essential drug producer in Tamil Nadu in a 2020 Lok Sabha reply filed by the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers.

In every case of cough syrup poisoning, DEG or EG [ethylene glycol], the toxic industrial solvents, were found contaminating syrups. The law says every medical shop should have a qualified pharmacist. But look around. Who are running all these medical stores, especially in the rural belt of North India?

-Dr Kafeel Khan

But manufacturing issues are only one part of the story. Poor oversight by regulators, careless prescribing, and low consumer awareness complete the chain of failure.

Dr Kafeel Khan said several drug combinations banned more than a decade ago for their potential to harm children remain on pharmacy shelves. These include Chlorpheniramine + Codeine Phosphate + Menthol; Dextromethorphan + Chlorpheniramine + Ammonium Chloride + Sodium Citrate + Menthol; and Ambroxol + Terbutaline + Ammonium Chloride + Guaiphenesin, among others.

“In every case of cough syrup poisoning, DEG or EG [ethylene glycol], the toxic industrial solvents, were found contaminating syrups,” he said. In October 2023, CDSCO found that a cough syrup and an anti-allergy syrup made by Norris Medicines were contaminated with DEG and EG. This came soon after the same chemicals in Indian-made cough syrups were linked to the deaths of 141 children in Gambia, Uzbekistan, and Cameroon.

Cough syrups, Khan noted, are often prescribed for routine colds, which “will go away in seven days if treated, and ten days if not.”

Such medicines are overprescribed because of social and commercial pressure, he added. If a doctor doesn’t give any medicine, parents go to another doctor. So even when a syrup isn’t needed, doctors end up writing it to keep their practice alive.

On top of this, pharmacists, who could serve as the last line of defence, are often missing.

“The law says every medical shop should have a qualified pharmacist,” Khan said. “But look around. We don’t have that many pharmacists in India. Who are running all these medical stores, especially in the rural belt of North India?”

Also Read: Dementia research among rural north Indians is underway. NBRC study will change global views

‘What price on our babies?’

Thirty kilometres from Chhindwara town, Parasia feels like a place caught between past and progress. Once known for its coal mines, its narrow lanes are now filled with the sounds of motorbikes, cattle bells, and the occasional ambulance. At dusk, as the Satpura hills turn purple, the boards of shops light up, including the many pharmacies.

But across Chhindwara district, doctors and hospitals are far scarcer than the chemists doling out drugs. For many families—36 per cent of whom belong to Scheduled Tribes, mainly Gond and Korku communities—reaching professional medical care means hours of travel. For serious conditions, many end up going to Nagpur, about 125 km away, or Bhopal, 280 km from the district.

Parasia links dozens of villages but medical care is woefully inadequate. The civil hospital, upgraded from a community health centre only last year, still lacks key facilities for paediatric and critical care. There is no dialysis unit in the district, and an ambulance to Nagpur costs Rs 5,000–6,000.

Most families work in farming or mining and can just about afford the Rs 300 consultation at a paediatrician’s clinic.

Since the Coldrif tragedy, several pharmacies have downed their shutters—some out of fear of losing their licence, others after Coldrif bottles were found on their shelves. The tragedy dominates local conversations and social media.

Among those forced to shut is an Ayurvedic shop, across from Soni’s clinic. Dust gathers on the counters now. Sumit Raseela, the brother of the owner, said Soni was a trusted figure in the village.

“We trust the doctor and the medicine he prescribed. He would never give medicine to kill anybody,” Raseela, 35, said. Like most families in the area, his own children had also taken Coldrif. He has been going to Dr Soni since childhood, as does most of the neighbourhood. There’s only one other paediatrician in town.

Eleven kilometres away, in Sethiya village, Suresh Peepree Khatik sits outside his yellow-painted home, his phone playing a short video of his daughter Rishika dancing—the night she fell sick.

The five-year-old developed a fever on 25 August and was given Coldrif. Tests later showed her creatinine level had spiked to 5.73, far above the normal range of 0.6-1.3 mg/dL, indicating kidney failure. She underwent nine rounds of dialysis before her death on 16 September.

The family sold jewellery and borrowed from relatives, raising Rs 14 lakh in days to try to save her.

“We’re farmers, and we don’t have the money, all doctors were only referring us to private hospitals, I went and begged for a treatment at AIIMS-Bhopal but nobody heard me,” Khatik said. It has only six paediatric beds.

Neither the Parasia civil hospital nor Chhindwara district hospital had the facilities to treat her either.

Now, Rishika’s drawings and new Spiderman school bag are among the few traces of her they have left.

“She wanted to become what killed her—a doctor,” he said.

Khatik has refused to be assuaged by the Rs 4 lakh compensation offered by the government.

“I told the officials who met me, I’ll give you Rs 8 lakh. You bring back my daughter. What price are you putting on babies?” he said.

With inputs from Prabhakar Tamilarasu.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

The 95% responsibility of this adulterated drug is on the manufacturer who did not produce it according to cGMP norms which the staff should have rigorously followed. Every drugs manufacturing factory has a qualified manufacturing, quality control and microbiology expert who are responsible for manufacturing and releasing of drugs according to cGMP regulations. Not adhering to them is crime.